The Benefits of Goblet Squats & Front Squats

Squats are the biggest lift, engaging the most muscle mass and stimulating the most muscle growth. And of all the squat variations, front squats are the best for building muscle.

Powerlifters have low-bar squats, which allow them to lift more weight. Athletes have high-bar squats, which allow them to focus on their quads. We usually use goblet squats and front squats, which allow us to stimulate more overall muscle growth, especially in our postural muscles.

Front-loaded squats are a better default for almost everyone else. They let us squat deeper, thicken our back muscles, straighten our posture, and bulk up our serratus muscles. They’re also the safest squat variation, rivalled only by safety-bar squats and hack squats.

Here’s why.

What are Front-Loaded Squats?

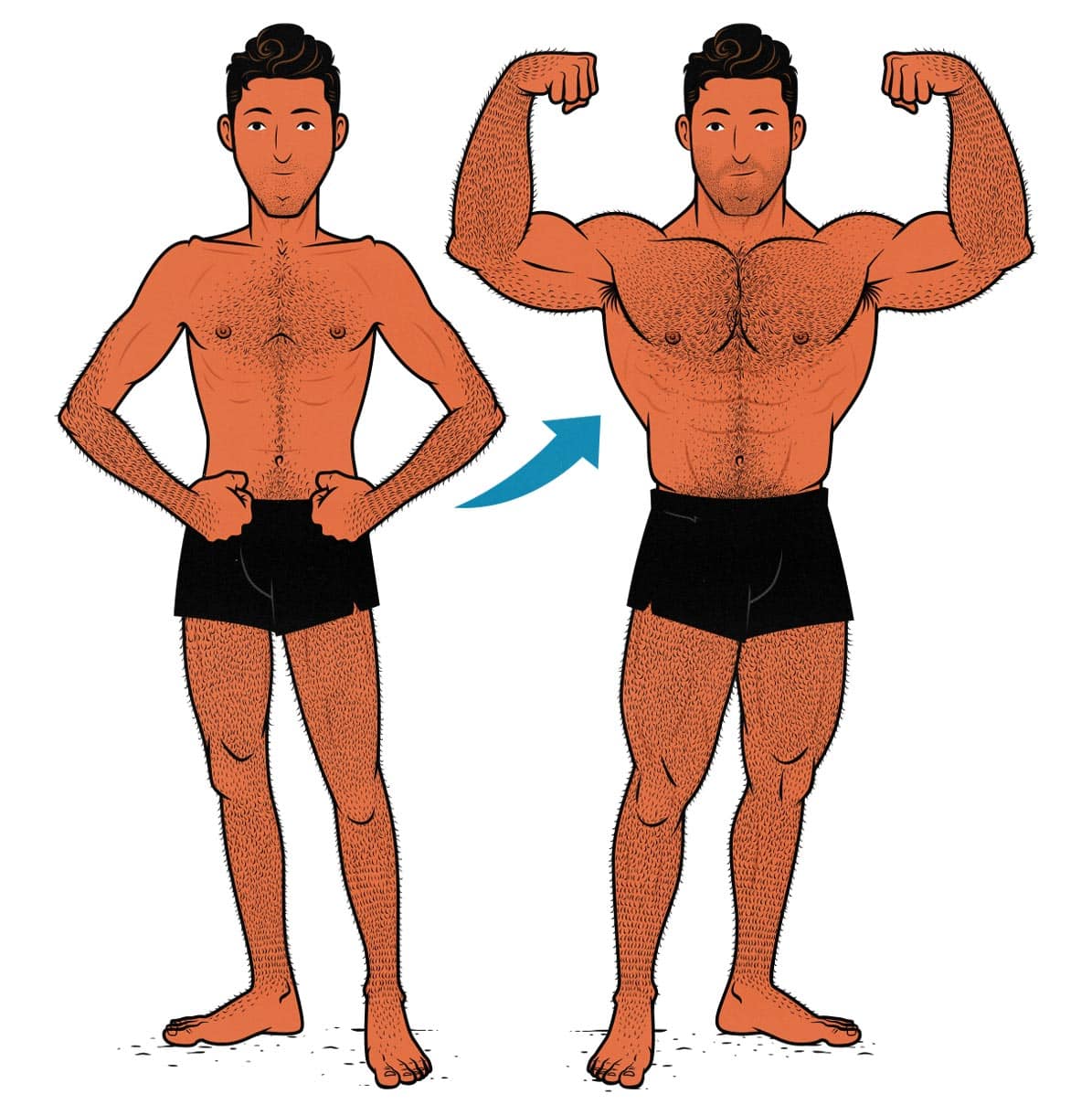

Before we talk about the benefits, let’s clear up what we mean by front-loaded squats. Front squats are usually done with a barbell, but you get the same benefits from any squat where you hold the weight in front of your body. That includes barbell front squats, goblet squats, Zercher squats, zombie squats, and so on.

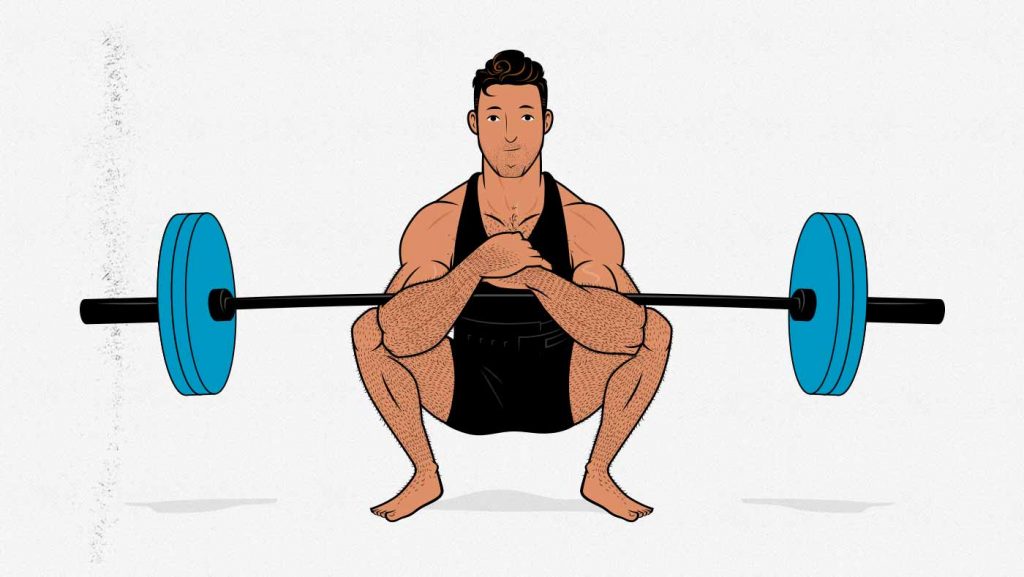

The goblet squat is the best variation for beginners, but it’s not just a beginner’s lift. It remains one of the best bulking lifts until we grow too strong for them—until we can do 12+ reps with the heaviest dumbbells we have access to.

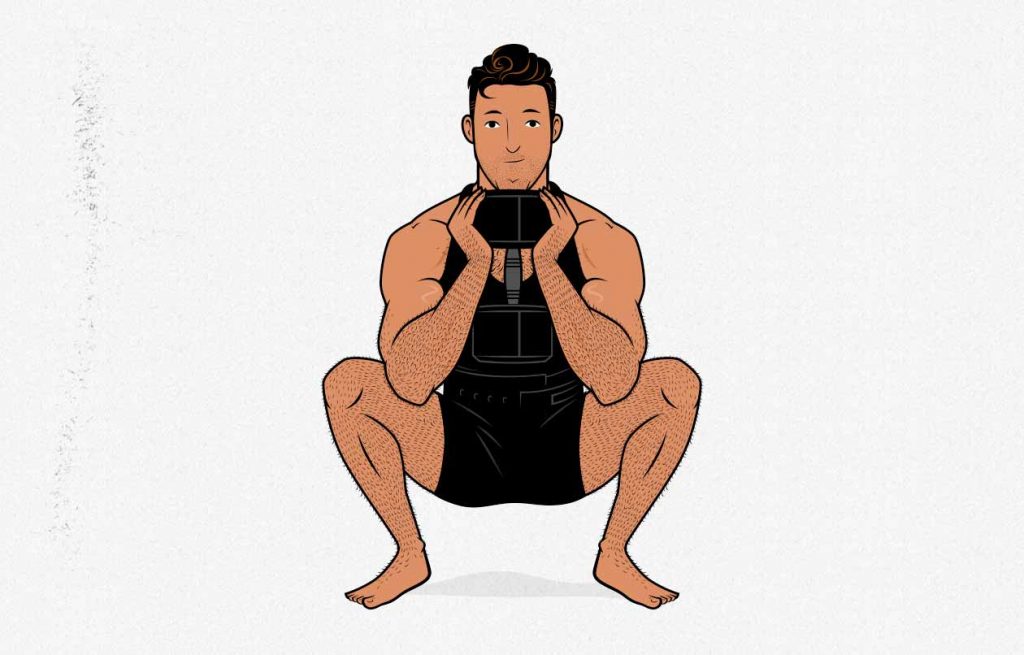

Once we get too strong for goblet squats, there’s the option of holding two dumbbells in a racked position. If you have a barbell, though, it’s a great time to learn the classic front squat:

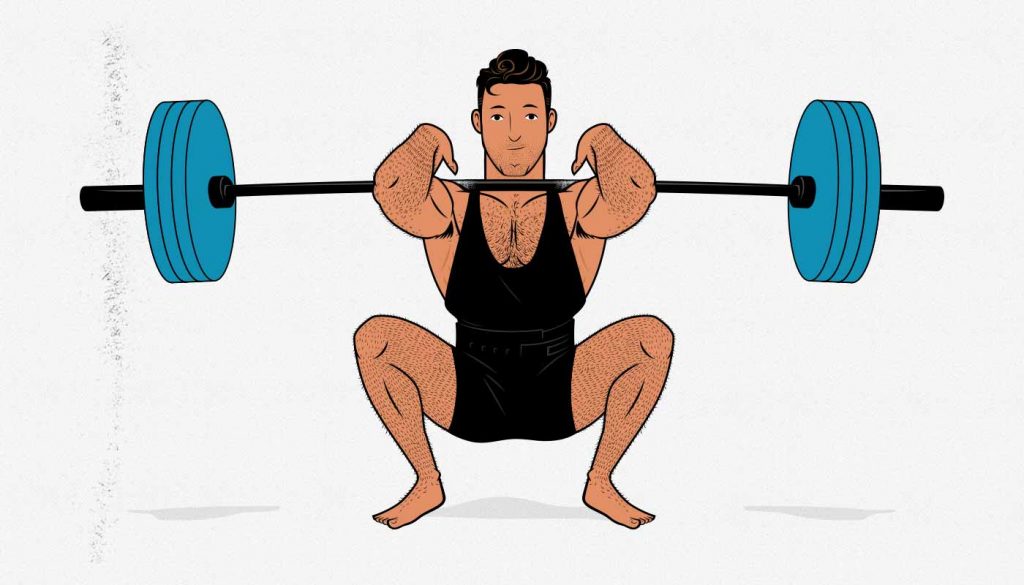

The front squat has us holding the barbell in front of us, in the crease between our collarbones and shoulders. You can load it up progressively heavier without fear of outgrowing it.

There are strange variations, too. The Zercher squat has us holding the barbell in the crook of our elbows, supported by our biceps and traps. It’s an advanced combination of the front squat and the goblet squat.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll be talking about all types of front squats. They’re all slightly different, but they all shift the weight forward, giving us a slew of benefits. Let’s delve deeper into those benefits.

Front Squats Work Our Upper Backs

Some people think of the classic back squat as a full-body lift, others think of them it as being a leg lift. Both groups are right.

- A back squat is a full-body lift in the sense that it will improve our overall health and fitness. It puts a great strain on our bones, tendons, ligaments, and even our cardiovascular system, provoking a number of great full-body adaptations.

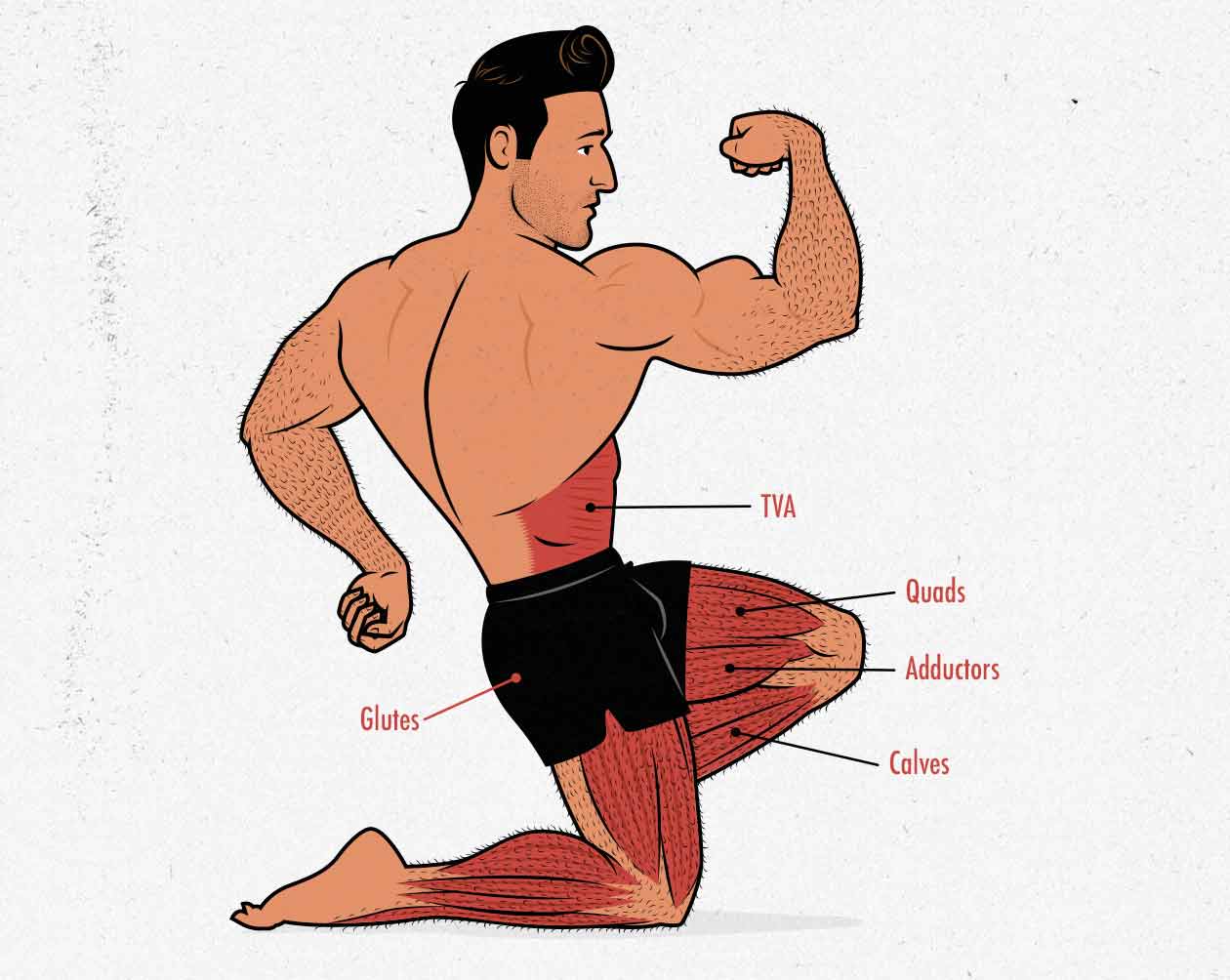

- But back squatting won’t build muscle in our upper bodies. Only our quads, glutes, and adductors will be brought close enough to failure to stimulate a robust amount of muscle growth.

That isn’t to downplay the value of the squat. Our quads and glutes are the biggest muscles in our bodies, so any lift that challenges them will allow us to build a tremendous amount of overall muscle. It’s just that all of that muscle will be in our lower bodies, like so:

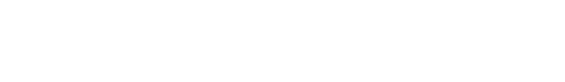

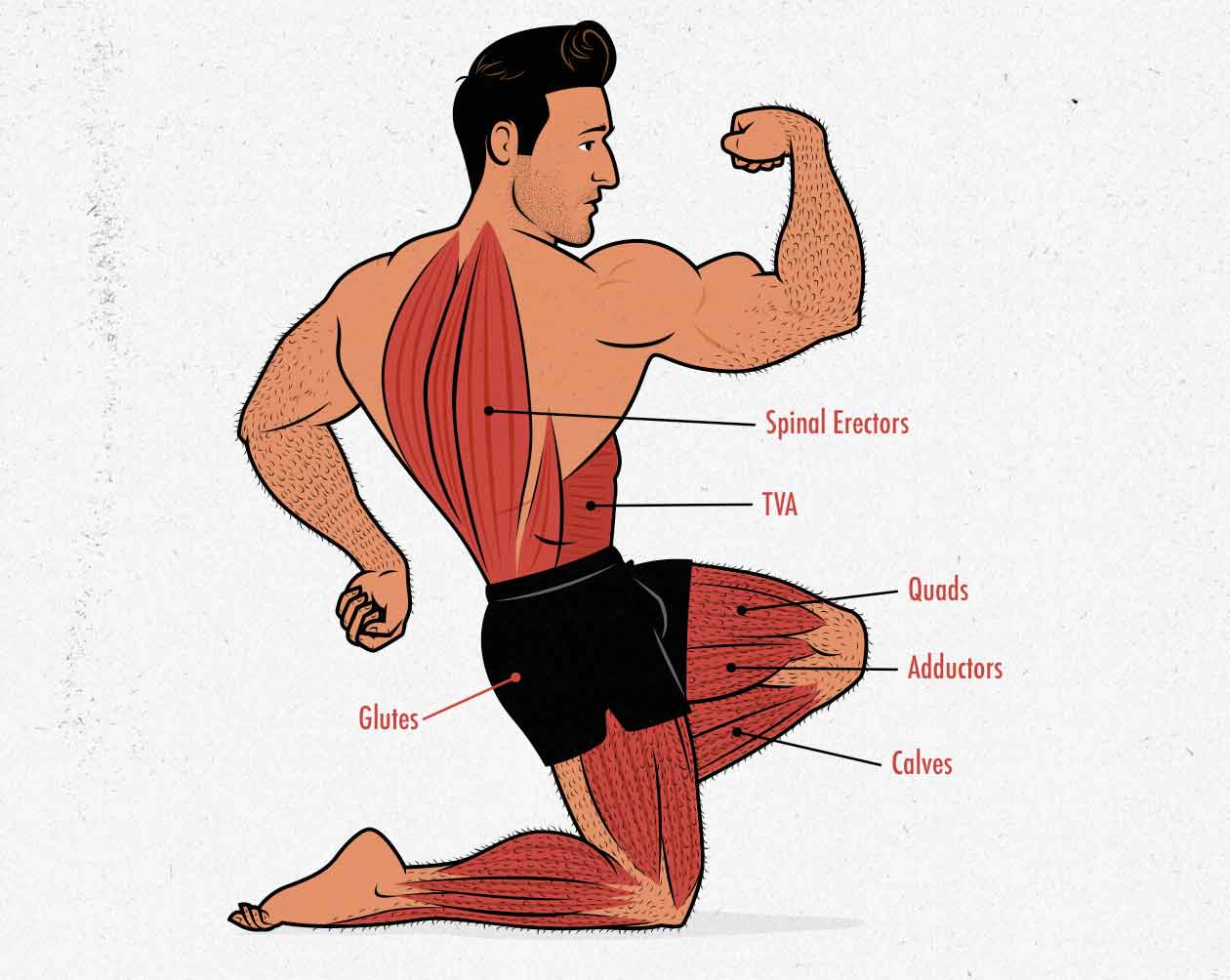

A front squat, on the other hand, is a true full-body lift. We get all of the aforementioned health and fitness benefits but also build a ton of muscle in our upper bodies, like so:

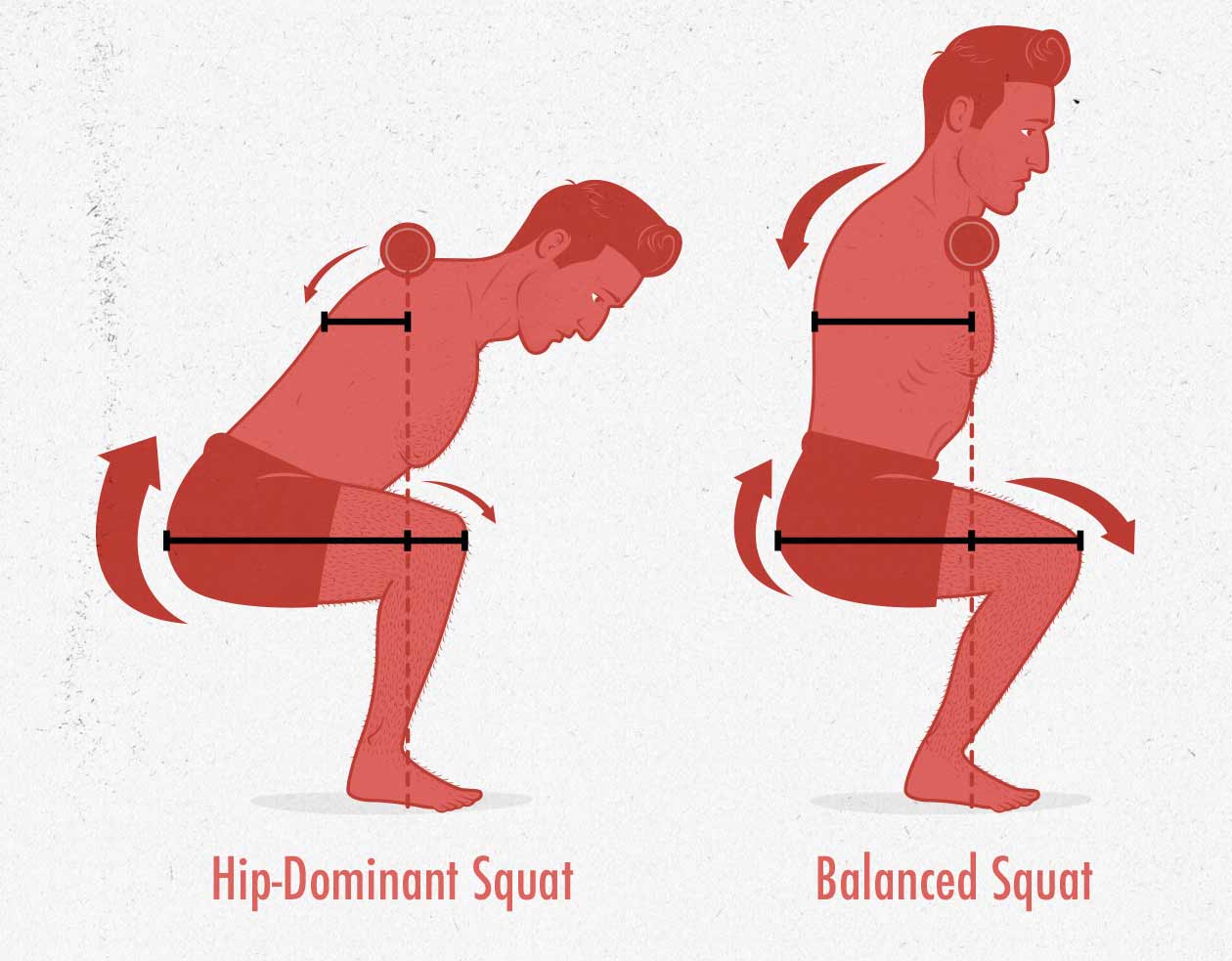

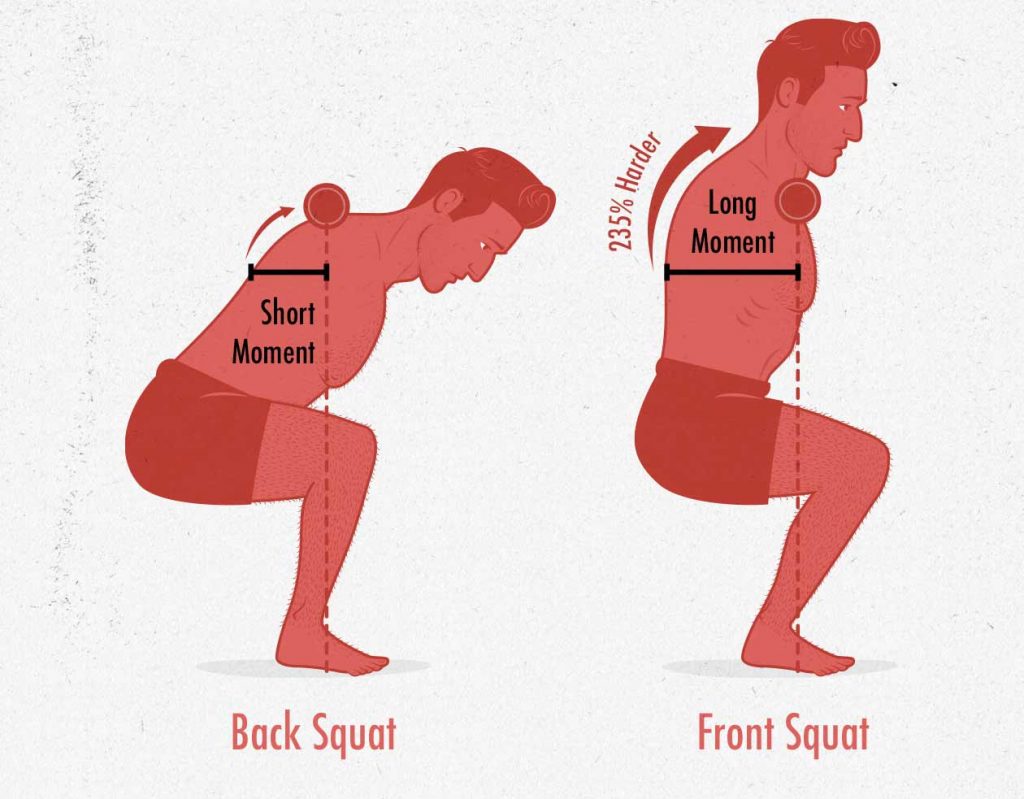

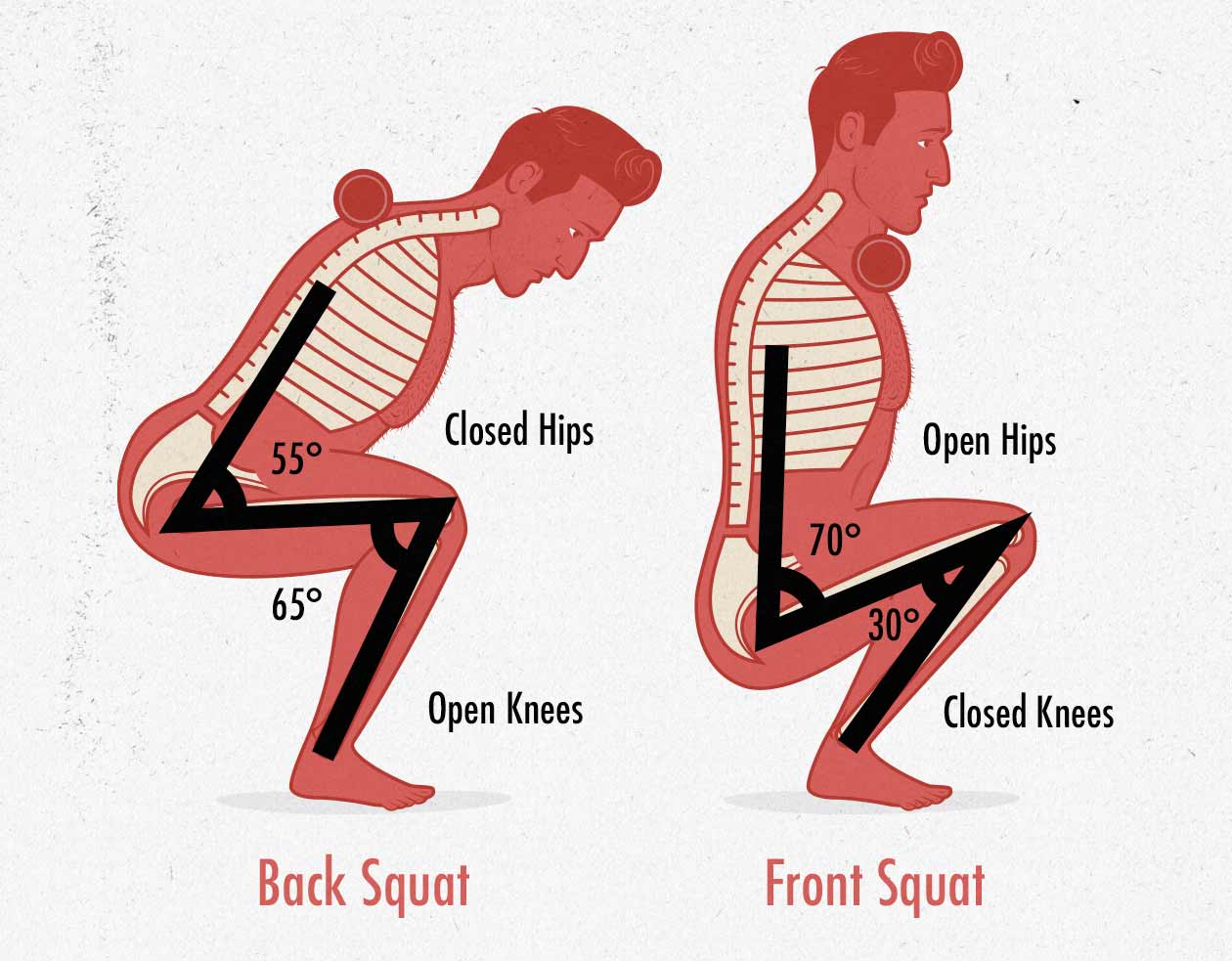

Weirdly, moving the barbell in front of our necks would bring in so much extra muscle mass. To understand why that is, we have to look at how it changes the physics of the lift:

The moment arms are calculated at the sticking point of the squat. Here’s what that means:

- Moment arms are the horizontal distance between our joints and the weight. The longer the moment arm, the harder it is for our muscles to lift the weight.

- The sticking point is where our muscles contract the hardest, stimulate the most muscle growth, and where most people lose the momentum they need to squat the weight up. The hardest part of the squat is when our femurs are parallel to the ground.

Now take a look at the moment arms for the upper body. The low-bar squat is easy for our backs to support. The front squat isn’t. It’s incredibly challenging for our spinal erectors, stimulating muscle growth in our upper backs. Greg Nuckols, MA, calculated that front squats work our upper backs 235% harder than back squats (source):

The obvious benefit is we’ll build more muscle in our upper backs, but there are a couple of secondary advantages, too:

- Front squats are a better accessory lift for the deadlift, given that they strengthen our spinal erectors.

- Front squats do a better job of improving our posture, given that our spinal erectors help us stand taller and straighter.

Front Squats are Better for Our Posture

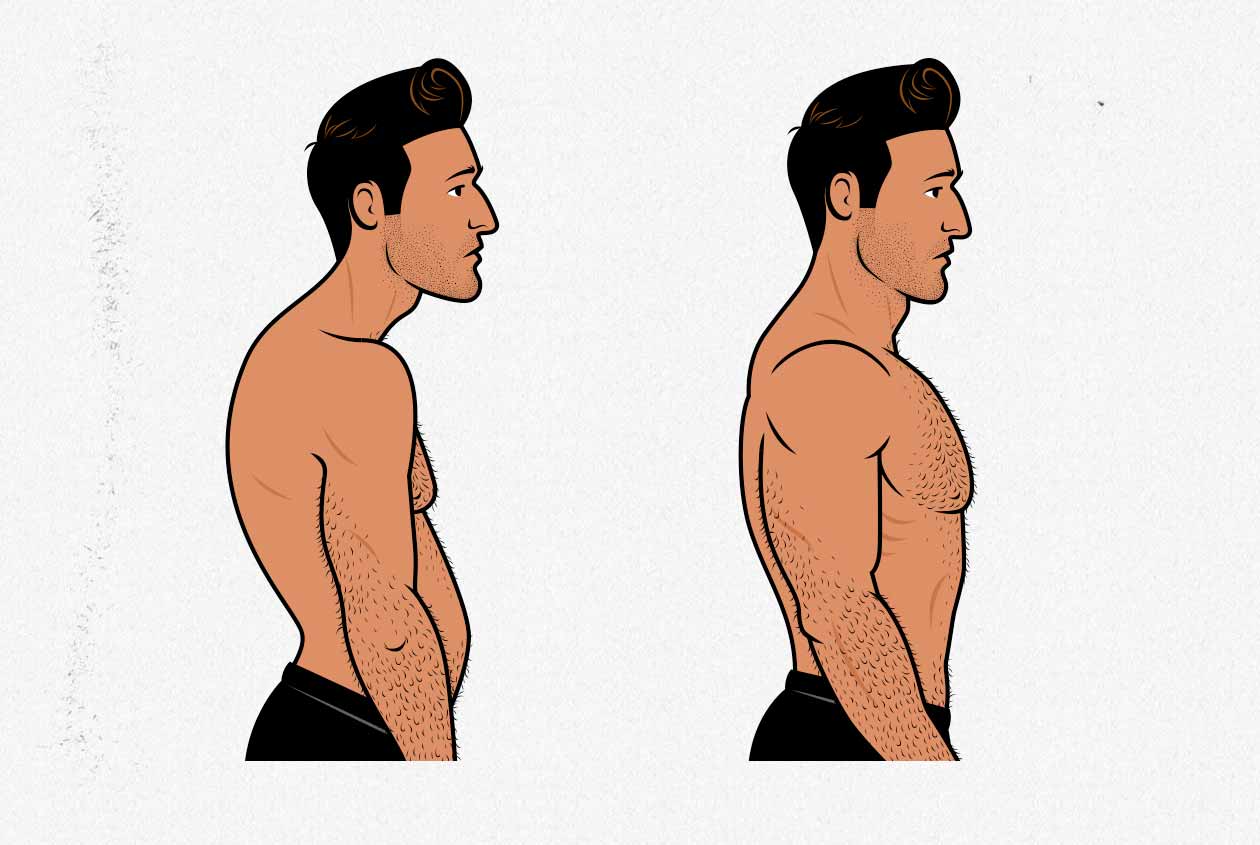

When it comes to our aesthetics, most people look like the fellow on the left but would rather look like the man on the right. Front squats are a great way to do that. They bulk up our spinal erectors, strengthen our backs, and improve our posture (study).

Conventional deadlifts are great for improving the strength of our spinal erectors, too. Even overhead pressing can help. But front squats may be the single best lift for improving posture.

If your upper back muscles can keep you from caving forward while holding hundreds of pounds in front of you, it will be easy to hold your chest up in your everyday life.

Front Squats are Better for Bodybuilding

One criticism of front squats is they’re lighter than back squats. That’s true: most people can low-bar squat 35% more weight than they can front squat. The assumption is that because front squats are so much lighter, they must not be as good for bulking up the quads, glutes, and adductors. Perhaps they’re better for our upper bodies at the cost of being worse for our lower bodies.

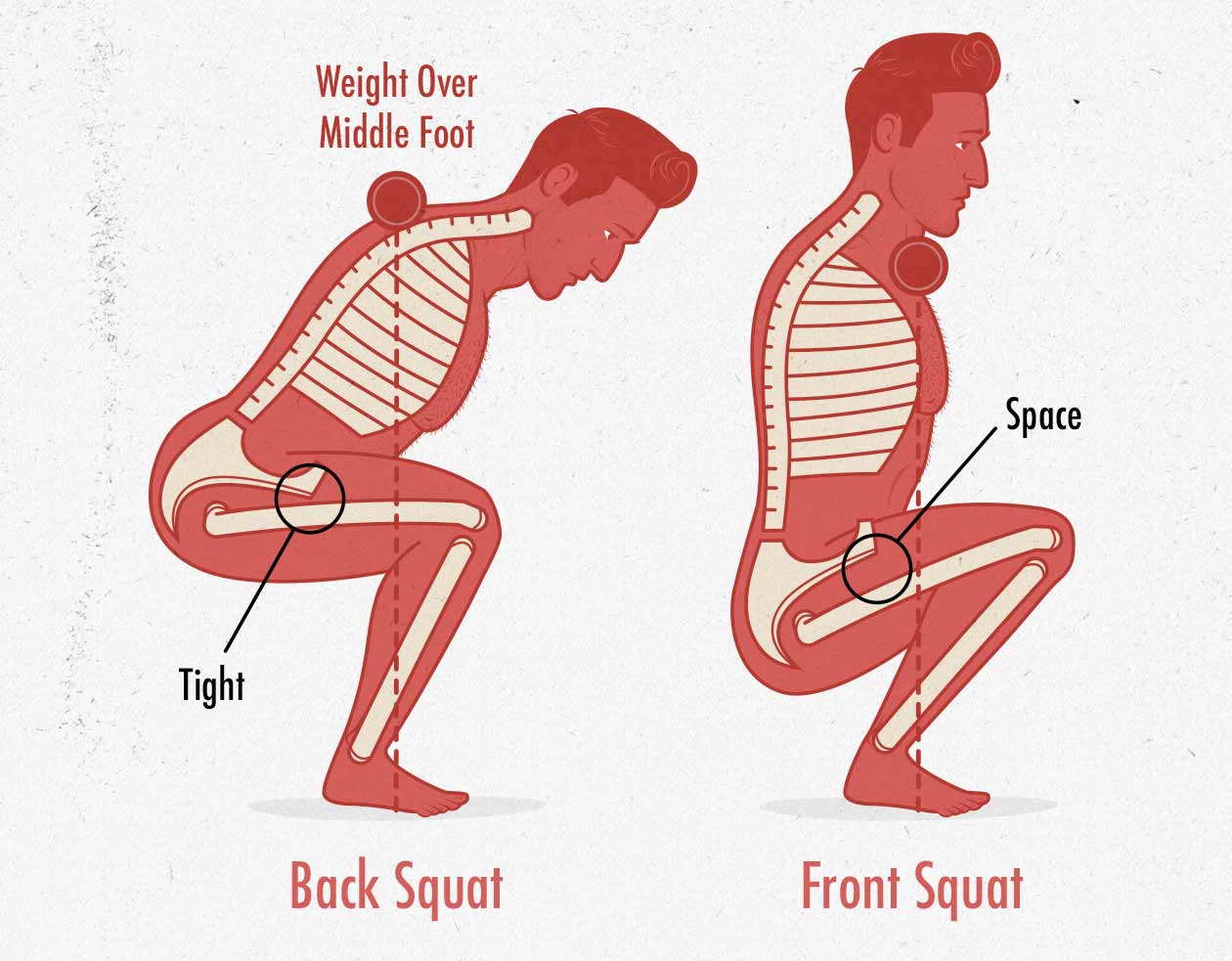

However, front squats allow us to sink much deeper, like so:

When we squat with an upright torso, our hips are tilted further back, and our hip angle at the bottom of the squat is lower, so we can get lower without our pelvises jamming up against our femurs. That space in our hips reduces the risk of hip injuries, and it’s better for improving flexibility, mobility, and general strength.

Going deeper also allows us to get a much tighter knee angle at the bottom of the squat. That tighter knee angle means we can work our quads through a deeper range of motion. A deeper range of motion stimulates more muscle growth and builds fuller quads extending further down our legs.

Front Squats Force Proper Lifting Technique

If you back squat with bad technique, you may still be able to muscle the barbell up by doing a sort of awkward good morning. With a front squat, though, as soon as you lean forward, the weight will tumble from your shoulders. Not only does that make front squats safer, but it also makes them great for learning how to squat with perfect technique.

How to Do Front Squats

When you first learn how to front squat, it will feel like being strangled by a barbell. You may need to stretch your forearms before you can grip the barbell properly. And even with those stretches, your forearm and finger tendons might still be stretched to the point of pain.

Here’s a video of Marco teaching the front squat. At the end, he goes over some stretches you can use to improve your forearm and shoulder mobility and flexibility, allowing you to hold the bar in a proper rack position (as opposed to using the cross grip). It will become comfortable with practice.

(You could also use a “cross grip” or “zombie” technique where you rest the barbell in the crooks of your shoulders instead of on your fingers. That works, too. Totally up to you.)

Conclusion

All squat variations are good. You can choose the one you prefer. However, when in doubt, go with front squats. They offer a slew of unique advantages, including some I didn’t cover above:

- Deeper range of motion: Front squats are done with an upright torso, allowing for a larger range of motion and making us less likely to jam our hips into our femurs.

- More upper back growth: Front squats are more challenging for our spinal erectors, helping us build bigger, thicker, straighter upper backs. This strength translates well to deadlifts.

- Front squatting is great for our spines: squatting with an upright torso puts our spines under plenty of compressive force, making our spines tougher. However, there isn’t much shear stress, reducing our risk of injury, and potentially making front squats less fatiguing than other variations.

- Front squats force better form: when front squatting, any deviation in technique dumps the weight. This means that even when squatting hard and approaching failure, front squats continue to reinforce good technique.

- Front squats are better for our posture and shoulders: Front squats improve t-spine mobility, improving our upper back flexibility and posture.

- Front squatting is easier on our knees. Most squat variations make our knees tougher (unless you have a preexisting injury). Front squats tend to be easier on people who already have cranky knees (study).

- Front squats are just as good at bulking up the quads and glutes: front squats are lighter, yes, but since we’re squatting deeper, it produces equal growth in our quads and glutes (study).

- Front squats bulk the lower portions of the quads: when we train our muscles at longer muscle lengths, it causes proportionally more muscle growth in the distal (lower) portions of our muscles.

Alright, that’s it for now. If you want to know the ins and outs of bulking up, we have a free newsletter. If you want a full muscle-building program, including a 5-month workout routine, a bulking diet guide, a gain-easy recipe book, and online coaching, check out our Bony to Beastly Bulking Program. We’ll teach you how to squat, too. Or, if you want a customizable intermediate bulking program, check out our Outlift Program.