How to Deadlift for Muscle Growth

Deadlifts are one of the only true full-body lifts. They challenge our muscles from our fingers down to our toes and stress our bodies from the skin on our palms all the way down to our bones. They’re hard, tiring, and absolutely amazing for building muscle, gaining strength, improving our fitness, and becoming much better-looking.

When it comes to bulking up, the only lift that can rival the deadlift in terms of sheer muscle growth is the squat (and especially the front squat). Even then, the deadlift has a few unique advantages:

- Deadlifts bulk up our traps, spinal erectors, and glutes, as well as a number of other muscles in our upper backs, all of which are great for improving our aesthetics.

- Deadlifts are one of the best ways to increase bone density and spine health, which is great for our health and longevity.

- The strength we develop with deadlifts transfers near-perfectly to our daily lives, making us look strong because we are strong.

- Squats and deadlifts train different muscles, with the front squat emphasizing the quads and upper back and the deadlift emphasizing the hamstrings, glutes, and entire back.

As with all the big lifts, though, there are several different ways of deadlifting, each with different pros and cons. And given how many different sorts of adaptations deadlifts provoke, it’s not surprising that some ways of deadlifting are much better for building muscle than others.

Most guys who are interested in strength favour the conventional deadlift. That’s wise—and we’ll explain why—but they deadlift for low reps and drop the bar to the ground after every repetition, making it worse for building muscle mass.

The most heinous sin, though, belongs to the bodybuilders who forego the deadlift altogether, thinking it isn’t a good lift for gaining muscle. That couldn’t be farther from the truth.

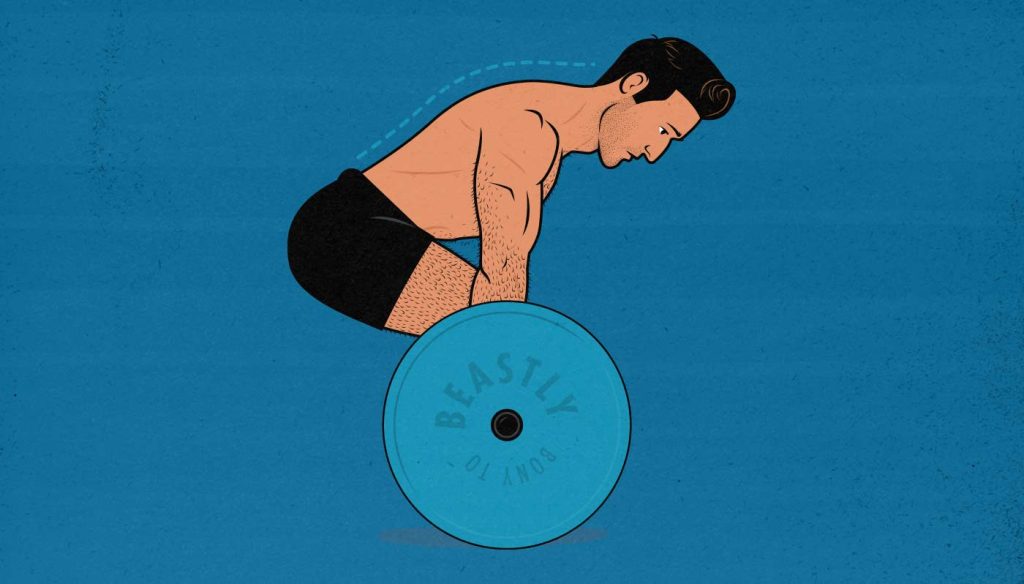

What Is a Conventional Deadlift?

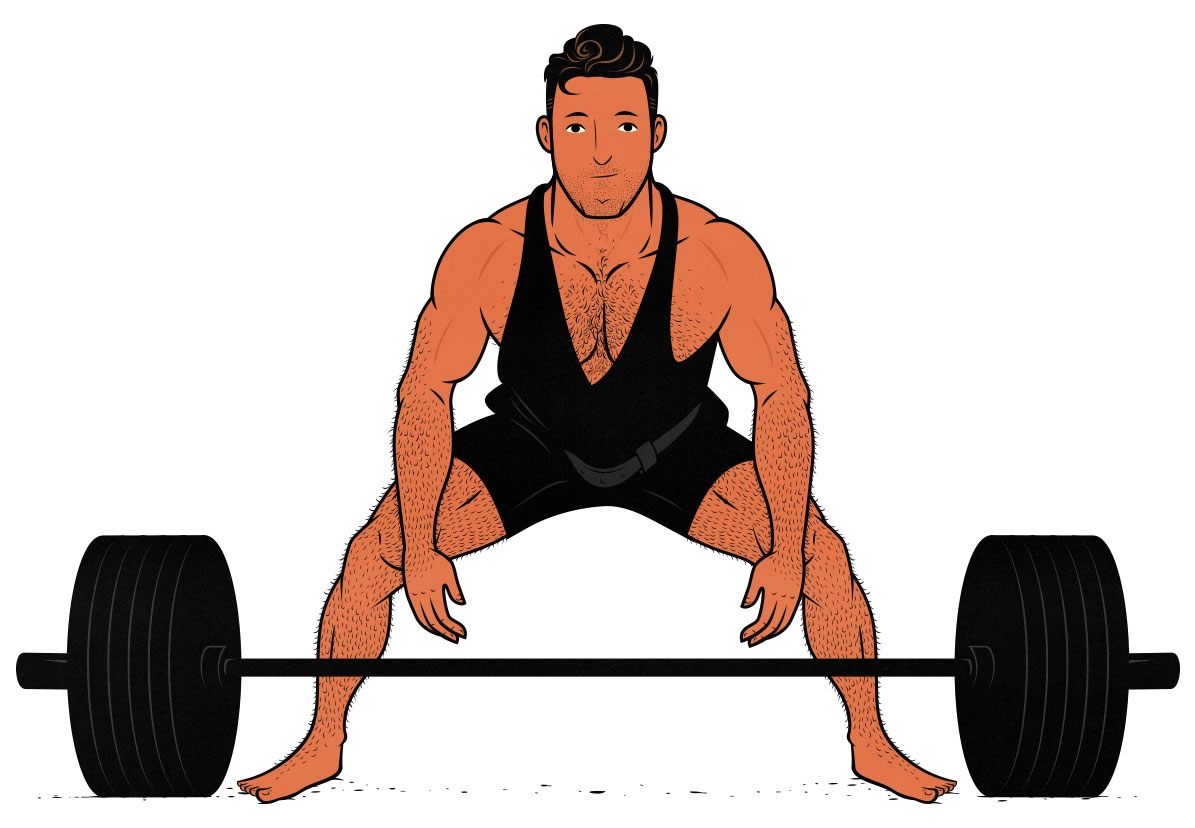

There are a few different ways of deadlifting, ranging from the Romanian deadlifts (which are great for our hips) to sumo deadlifts (which are great for our quads). The conventional deadlift is the normal, “conventional” way of deadlifting, where we set up with a fairly narrow stance and lift the barbell from the floor, like so:

What makes the conventional deadlift special is that it’s perhaps the only bonafide full-body lift. Yes, you might call back squats full-body lifts. And yeah, they work our spinal erectors. But probably not enough to provoke much muscle growth, especially once you get beyond the beginner level.

But with a deadlift, you’re just as likely to fail because of leg strength, hip strength, back strength, or grip strength. It’s one of the only lifts where your limiting factor could be your arms, torso, or legs. And that means that it actually does quite a good job of brining all of those muscles close enough to failure to stimulate a robust amount of muscle growth.

What Muscles Does the Deadlift Work?

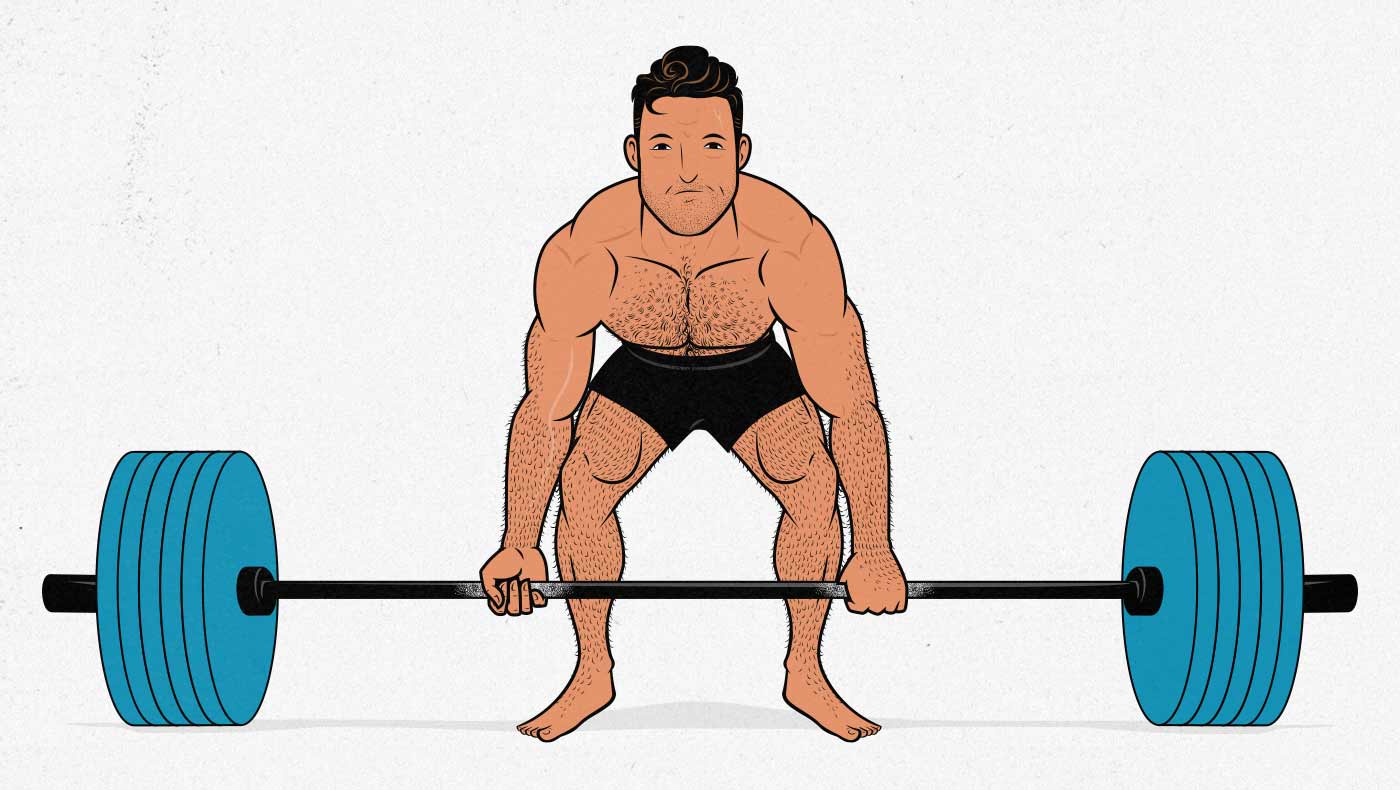

The deadlift is technically a hip hinge. We lift the weight up by flexing our glutes and hamstrings, by thrusting our hips forward. It also works those muscles through a full range of motion and challenges them under a deep stretch, which is fantastic for stimulating muscle growth.

But to keep our backs from rounding over, we also need to stabilize our spine with our spinal erectors. And because the weight is so heavy, it’s actually quite common for people to reach failure on the deadlift because their spinal erectors are fatigued. That gives them a great growth stimulus as well.

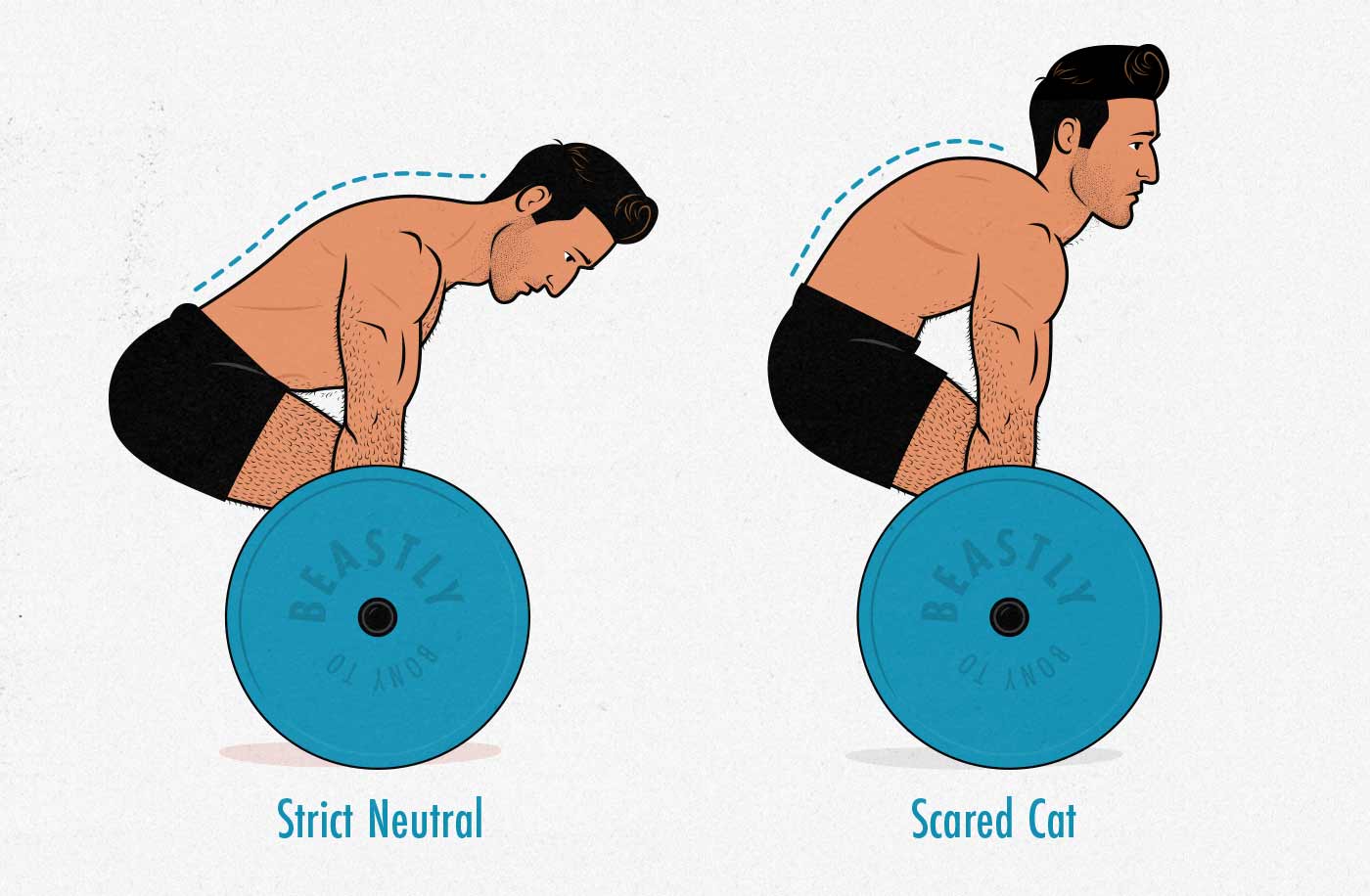

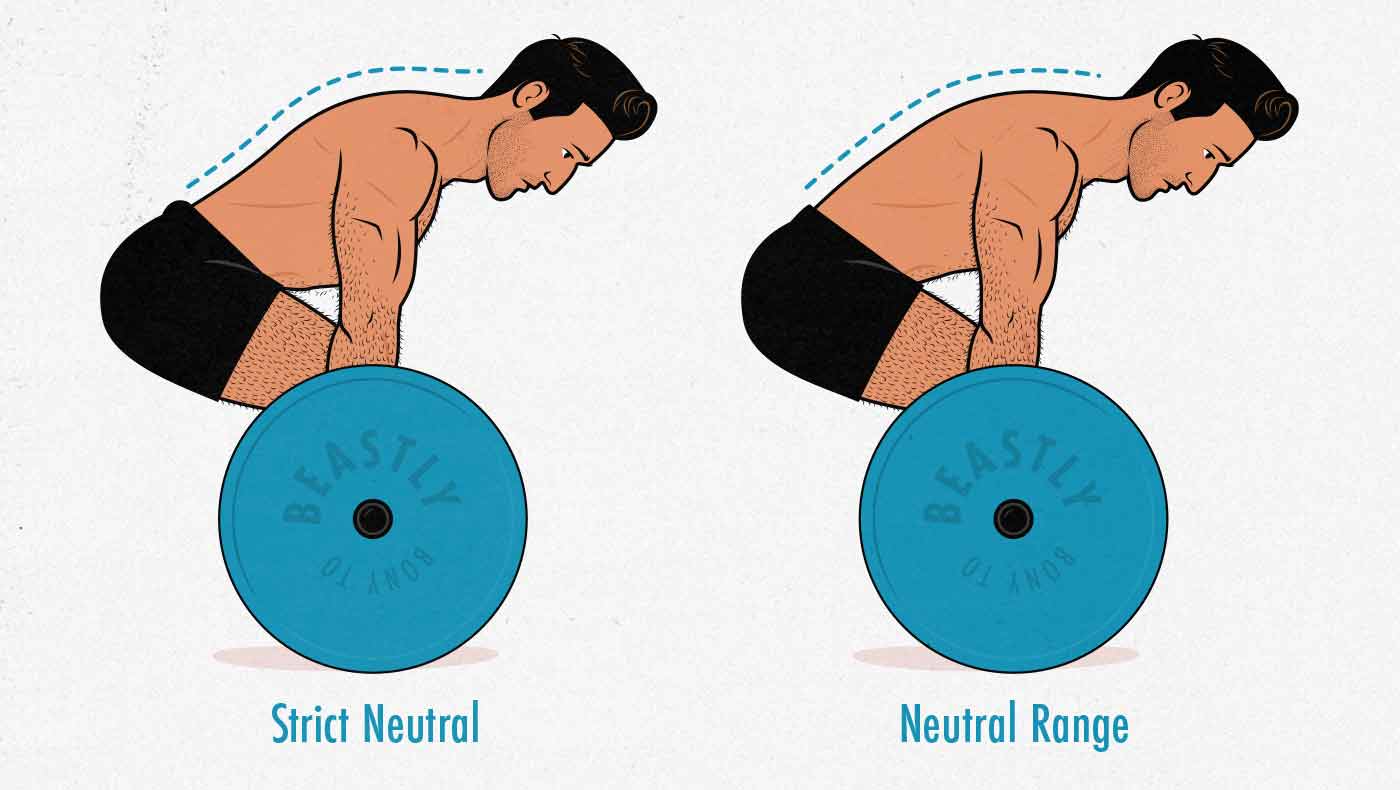

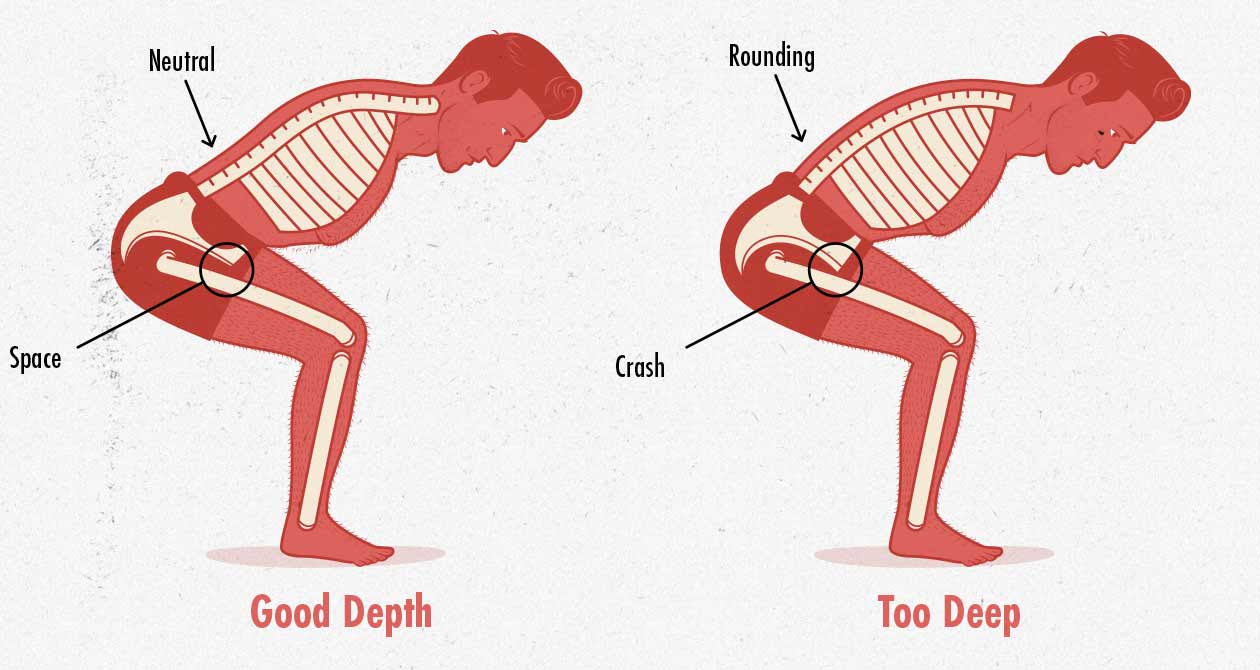

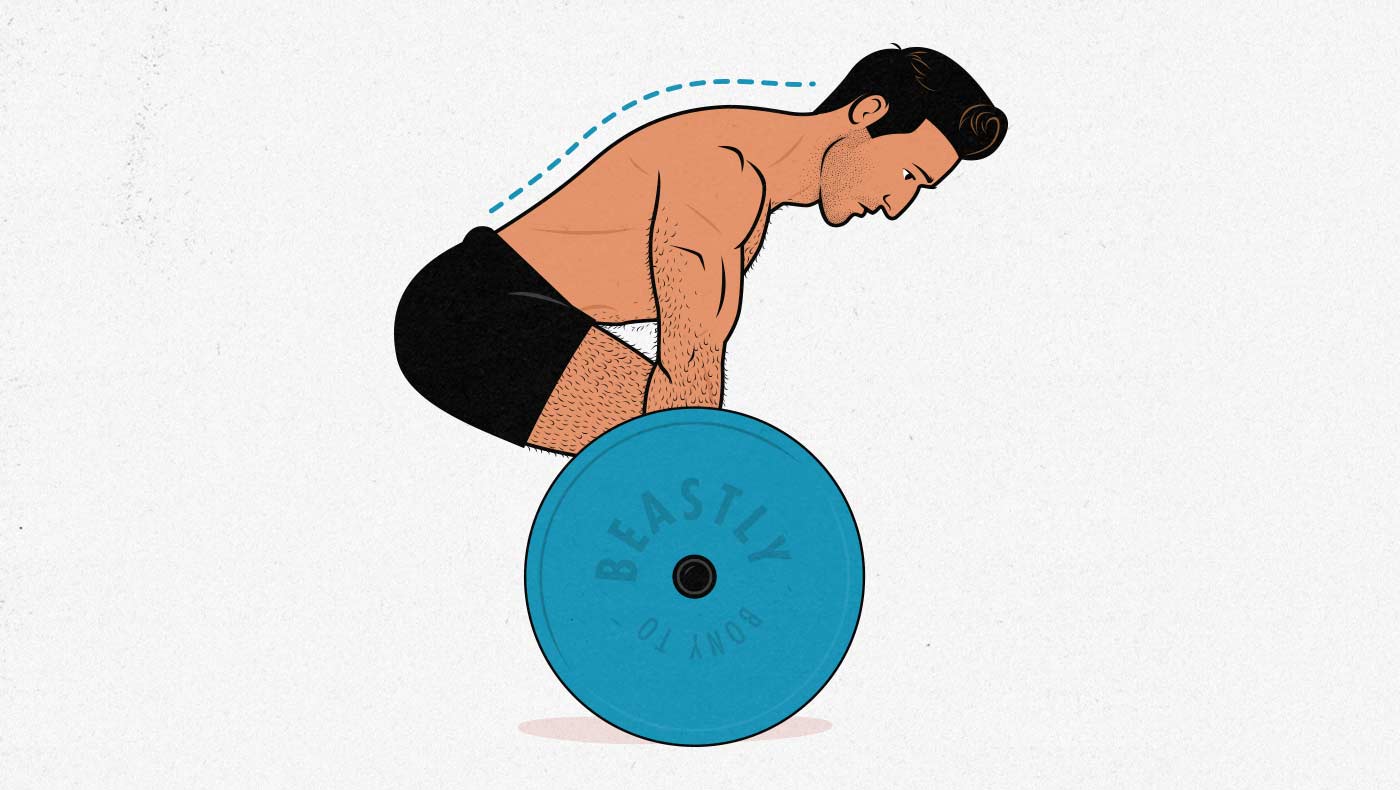

You’ve probably heard of the dangers of letting your back round in the deadlift. And that’s true. Excessive rounding puts more shear stress on the spine, which can increase our risk of injury. That’s why you’re not supposed to deadlift with the “scared cat” form shown above.

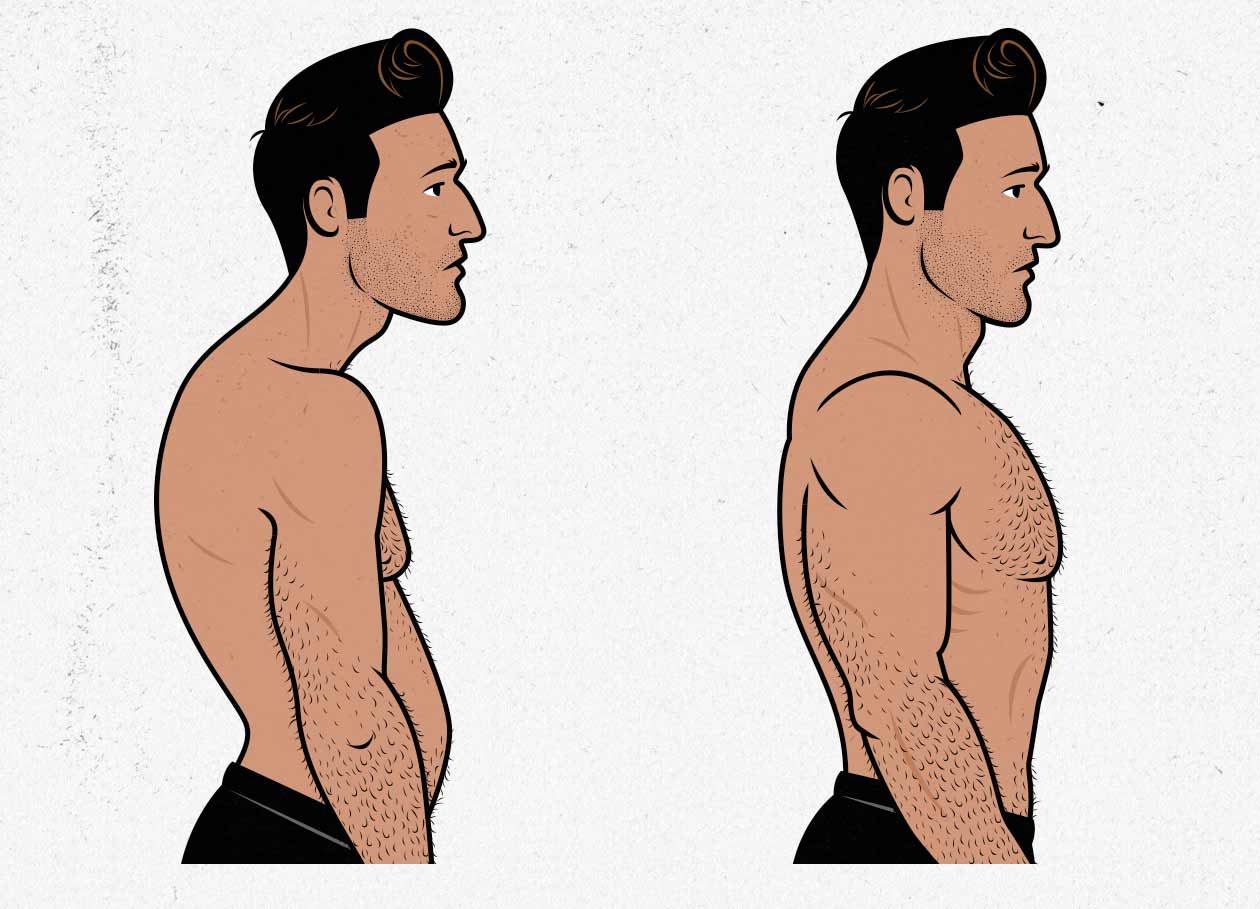

As you deadlift heavier and harder, your spinal erectors will stretch out a bit, putting themselves into a stronger position, and allowing you to bear greater loads. The spine is still within the neutral “range,” keeping the risk of injury low. And to lift maximal weights, that’s what’s often required. Deadlifts are a lift that truly work our spinal erectors. This not only makes them bigger, but it often allow us stand with stronger posture, too:

There are other muscles being worked as well. Our traps are loaded heavy under a deep stretch, doing such a good job of bulking them up that we’ll probably never need to perform a shrug. And our lats fight to keep the barbell in close to our legs, often getting quite a good stimulus as well.

Finally, we have our grip. The deadlift is a great exercise for improving our grip strength, and for a beginner, it’s one of the very best. The problem is, as an intermediate lifter, we don’t want our grip to limit us, which is why you’ll see people deadlifting with a mixed grip (one hand overhand, the other underhand), with chalk, with a hook grip (with their thumb hooked underneath the barbell), or with lifting straps. All of these methods make sense, and it goes to show that the deadlift works our grip so hard that we need to find ways to make it easier on our grips. (Keep in mind that strengthening your grip won’t bulk up your forearms, though. Those are different muscles.)

So to summarize, the deadlift is a great lift for bulking up our hips and hamstrings, amazing for bulking up our spinal erectors and upper backs, good for strengthening our grip, and even quite good for improving our posture.

Why Back Angle Affects Back Growth

Okay, now that we’ve gone over why we heap so much praise onto the conventional deadlift—the king of all bulking lifts—let’s talk about how different deadlift variations alter the training effects on our backs.

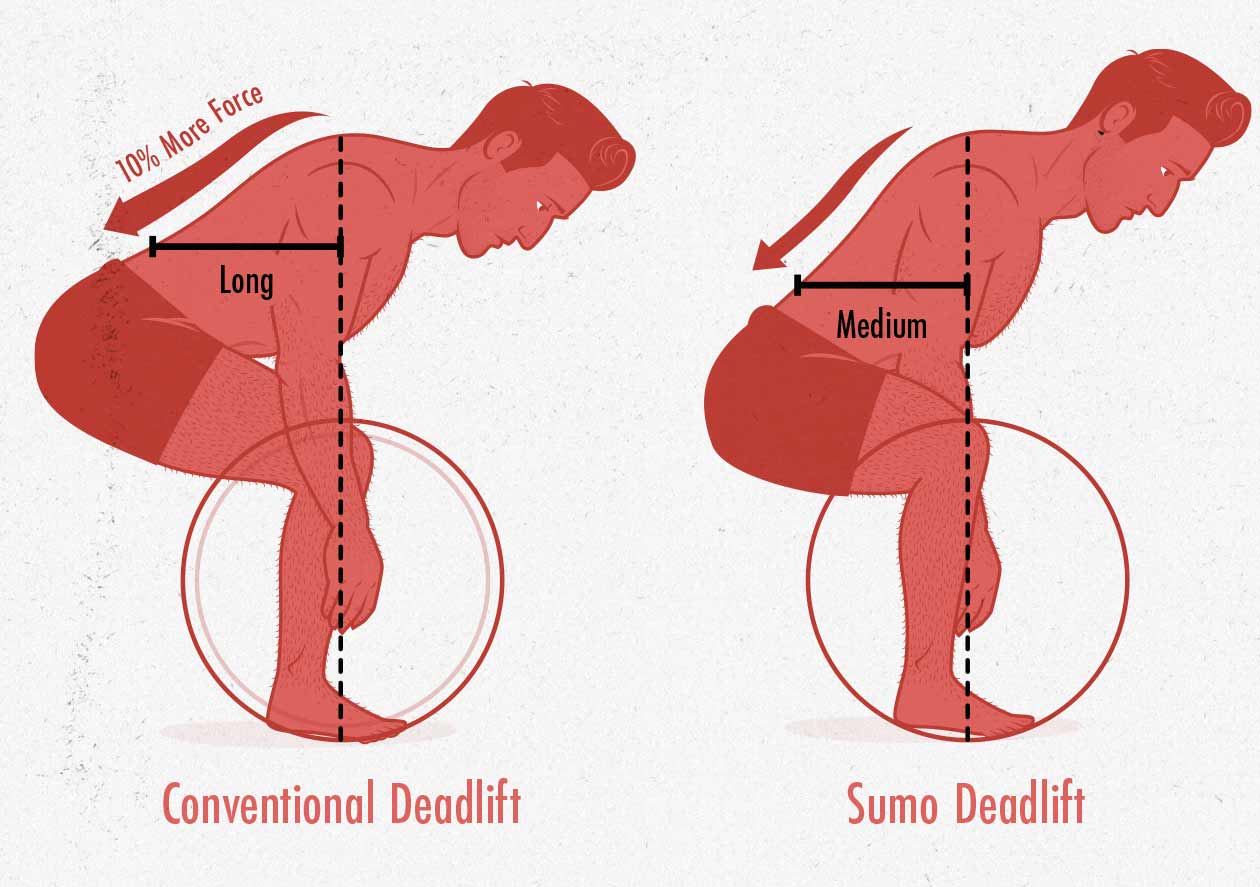

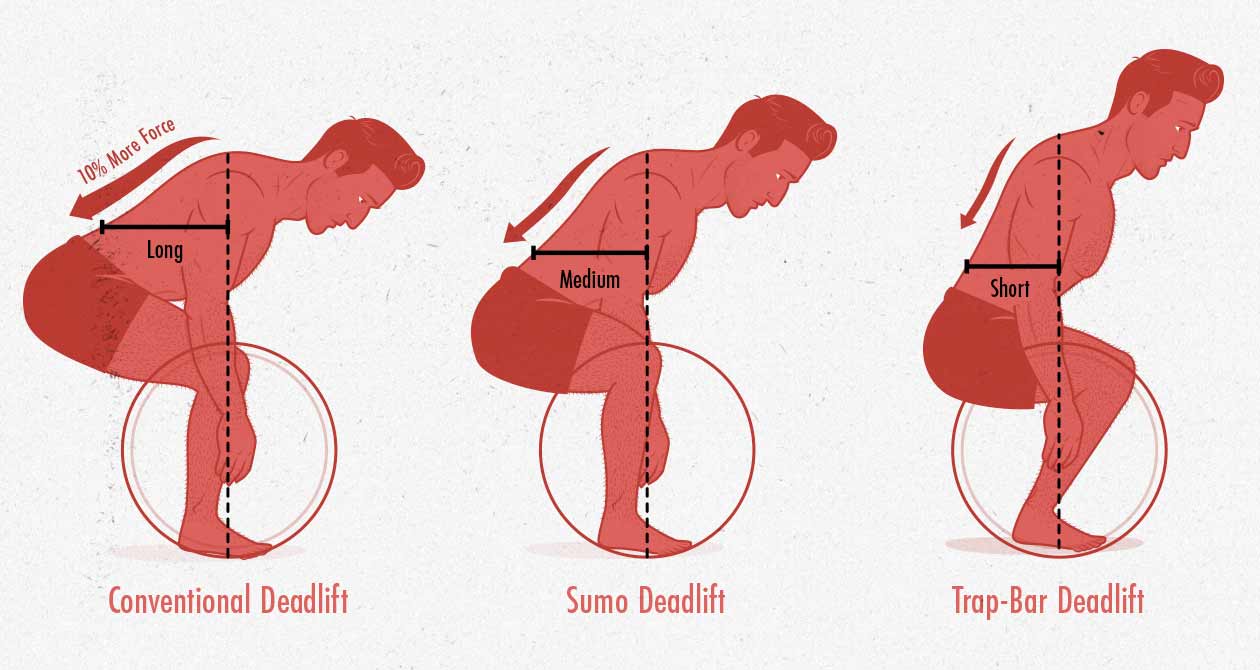

To figure out which muscles are being emphasized in different variations of a lift, it can be helpful to plot out the moment arms:

We’ve got a full article on moment arms, but without diving too deep into the physics, what we’re seeing here is that conventional deadlifts, at least in theory, are more challenging on our spinal erectors than sumo deadlifts. This pans out in the research, which shows that conventional deadlifts are about 10% harder than sumo deadlifts on our lower-back muscles.

One thing to point out is that in our article on front-loaded squats, we were drawing attention to the moment arms in our upper backs, whereas now we’re looking at the moment arms in our lower backs. That’s because while the front squat emphasizes the spinal erectors in our upper backs, the deadlift emphasizes the spinal erectors in our lower backs. This is important because our spinal erectors are tiny little muscles that only cross a couple of vertebrae. It’s not one set of muscles running all the way up our backs like a rope, linking our hips to our necks, it’s a series of little muscles that run up our backs like a chain, each link responsible for its own vertebra. Building a big and strong back means training all of our spinal erectors, and pairing front squats with conventional deadlifts is a great way to do that. (You may also want to include some neck extensions to bulk up the spinal erectors on the back of your neck.)

Now, there are plenty of skinny guys who have weaker backs, and thus are able to sumo deadlift quite a bit more than they can conventional deadlift. I’m one of those guys. The sumo deadlift is hard on my traps and hips, whereas the conventional deadlift is hard on my entire back. If I were a powerlifter, I’d do better pulling sumo, but I’m not. I’m interested in building a bigger, stronger, healthier, and better-looking body, and so the conventional deadlift suits my goals better.

This effect becomes even more exaggerated if we look at trap-bar deadlifts:

And the same logic holds. If our backs are our limiting factor, then any variation the minimizes the demands on our backs will allow us to lift more weight, and so trap-bar deadlifts would allow us to lift heavier without being limited by our back strength. Is that good? It depends. Are you trying to lift heavier or are you trying to build a bigger back?

Trap bar deadlifts also reduce our hip angle, increase our knee angle, and allow our quads to help us lift the weight. That makes trap-bar deadlifts a nifty blend of a squat and a deadlift, and perhaps the single best bulking lift of all time. However, we’re also minimizing what makes the deadlift so special and turning it into more of an all-around lower-body bulker.

To be fair, trap bars allow our knees and ankles to move any which way we like, so there’s nothing stopping us from driving our hips back and using the conventional technique even while holding a trap bar. That would allow us to get the back-bulking benefits of a conventional deadlift while still getting to take advantage of the trap bar (which is quite a bit easier to grip).

This is all to say that regardless of whether we use barbells or trap bars, if we’re using the deadlift to bulk up our backs, we’ll want to drive our hips back and lift with a conventional movement pattern.

How to Do the Conventional Deadlift

The deadlift is a surprisingly intuitive lift. After all, we’ve been doing them our entire lives, every time we pick something up off the floor. On the other hand, we may have ingrained some bad habits over the years, and if our default posture is poor, it might be hard to set up with a neutral spine.

When I first tried deadlifting, I had a lot of trouble bending in my hips instead of my lower back, even more trouble trying to brace and keep a neutral spine while lifting that weight up.

If you’re struggling with the conventional deadlift, it’s often better to start with an easier variation, such as a dumbbell sumo deadlift or a Romanian deadlift. Once those start to feel natural, try going deeper and heavier, eventually progressing to barbell deadlifts from the floor.

Range of Motion

The next thing to consider is the effective range of motion of the deadlift. We’re using the word “effective” because we don’t want to extend the range of motion so much that our back needs to bend at the bottom of the lift. That wouldn’t give us a greater training effect, it would just make the lift more dangerous.

So with the deadlift, what we want to do is set up the bar as low as we can comfortably go while still maintaining good technique. There are some guys who simply don’t have enough range of motion in their hips to do conventional deadlifts from the floor, but the vast majority of intermediate lifters won’t have a problem with it.

Lacking the mobility to deadlift properly is a super common issue for beginners, though, and so a lot of us benefit from starting with dumbbell sumo deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, raised deadlifts, or even a below-the-knee rack pulls before progressing to full deadlifts. Over time, we gain more mobility in our hips, our technique improves, and we can move down to the floor.

Once we can deadlift from the floor, we probably should deadlift from the floor, and there are a few reasons for that:

- The deeper we deadlift, the more we’ll need to bend in our hips, and so the larger the range of motion for our hips will be, improving our muscle and strength gains.

- The further down we go, the more our hips will drive back, and more horizontal our backs will go, improving the muscle growth in our backs.

- The longer the range of motion, the longer each rep will take, increasing the time under tension. Since our backs are working isometrically all through the lift, this further improves back growth.

- We’ll get more growth with less weight, reducing the fatigue that the deadlift generates, and reducing our risk of injury.

Where this gets even more interesting, though, is that even the deadlift variations that are done from the floor have different ranges of motion. The sumo deadlift uses a wider stance, which means we don’t need to lift the weight as high, and the trap-bar deadlift uses a higher grip, which means we don’t need to sink as low. Those are good solutions for people who lack the mobility to do conventional deadlifts from the floor, but most of us can learn to deadlift from the floor. And so again, the conventional deadlift shines.

Now, there’s also such thing as a deficit deadlift, where we raise our feet up on plates and extend the range of motion even further. There are also wide-grip and snatch-grip deadlifts, which force us to bend down deeper and then lift the bar higher. These are great bulking lifts for people who can handle them, but because they can be quite a bit lighter, we often use them as secondary lifts in addition to our heavier deadlifts.

There are also Romanian deadlifts, where we start in the top position and then drive our hips back as we lower the barbell down to our knees. These remove our quads from the lift entirely, and they create an even larger moment arm for our hips to overcome, forcing us to use far lighter loads. As a result, they’re great for bulking up our hips and hamstrings, but not nearly as good for bulking up our spinal erectors, traps, and upper backs. Again, they’re best used as a secondary lift to the conventional deadlift.

Of the deadlift variations, a conventional deadlift tends to have the best balance of range of motion and heaviness for building muscle, but this will vary from person to person.

Should You Drop the Weight When Deadlifting?

How quickly we lift and lower the weights doesn’t have a huge impact on how much muscle we build. Still, the best way to stimulate muscle growth is to lift explosively (to accelerate the bar) and then to resist gravity on the way down, lowering the weight under control (often taking 2–3 seconds). Lifting explosively helps to recruit as many muscle fibres as possible right from the beginning of the lift. Lowering the weight slowly helps to sneak in some extra muscle growth from the eccentric part of the lift.

With the deadlift, though, a lot of us toss this tempo out the window. Instead of lowering the barbell slowly and under control, we drop it down to the ground, let it roll out of position, and then take our time setting up for another rep. But if we’re deadlifting to build muscle, we want to approach it like we do our other lifts: resist gravity, lower it under control, and stimulate extra muscle growth on the way down. Then, once we’ve set the weight down, we can lift it right back up. Because we never lost control of it, we don’t need to reset our position, we can just keep lifting.

Also, keep in mind that lowering the barbell is the eccentric part of the lift for our hips, but for our spinal erectors, traps, and lats, the entire lift is isometric. If anything, we’ll stimulate more growth in our backs as we lower the barbell down because it will provide more time under tension.

As a result, the ideal deadlift tempo looks something like this:

- The setup: pull the slack out of the bar, get into a strong position, feel the tension on your muscles

- The lift: rapidly but gradually put all of your might into accelerating the barbell upwards.

- The lower: gently put the barbell back down, keeping your muscles fully in control of the bar, and keeping a strong position.

- Repeat: you don’t need to reset between reps if you never lost your positioning in the first place. Once you’ve put the barbell gently back on the ground, simply lift it back up again.

If you’re using the tempo to build muscle, you’ll want to use a similar tempo to your other muscle-building lifts. Accelerate the barbell up and then lower it down slowly and under control.

Should You Deadlift in Low Rep Ranges?

As we covered in our strength training and hypertrophy training articles, there’s no strict hypertrophy rep range, and we can technically build muscle with reps ranging anywhere from 4–40. Even so, more practically speaking, we tend to get more muscle growth more easily when doing 6–20 reps per set.

However, with deadlifts, we’re engaging a huge volume of muscle mass and lifting heavy weights through a large range of motion. There’s a lot of work being done, which can become extremely metabolically taxing as the rep ranges get higher.

Consider someone who can deadlift 405 pounds. For three repetitions, they’d be able to lift around 365 pounds, for a total of 1095 pounds lifted per set. But for twelve repetitions, they’d be able to lift around 285 pounds, for a total of 3420 pounds lifted per set. Even though the weight is lighter, lifting in the higher rep range still means doing about three times as much total work.

Now, because we’re talking about the amount of weight being lifted, the amount of work being done scales with our strength. For newer lifters who are in good cardiovascular shape, even higher-rep sets of deadlifts might not be that taxing. But for stronger lifters who don’t do very much cardio training, even low-rep sets of deadlifts can leave them gasping for breath on the ground for several minutes.

Another factor to consider is which variation of deadlift you’re doing. Conventional deadlifts have a larger range of motion and engage more of our back muscles, requiring more work to be done with every rep, and thus making them quite a bit more tiring than sumo, trap-bar, and Romanian deadlifts. Not by a small margin, either. This study found that conventional deadlifts used 25-40% more energy than sumo deadlifts.

Doing more work tends to be great for muscle growth and also has the advantage of being great for our cardiovascular systems. When we’re working so much muscle mass so intensely, it’s not so different from doing a bike sprint. Doing deadlifts for sets of 8–10 often becomes a form of high-intensity interval training (HIIT), which is absolutely brilliant for building muscle, gaining strength, and improving our general health and fitness.

However, if we push the rep range so high that we’re limited by our cardiovascular systems instead of by the strength of our muscles, then we’re transforming our bulking workouts into cardio workouts. Our bodies will see no need to gain more size and strength, just to improve our heart health and oxygen delivery. (This is why high-rep, low-rest circuit routines like CrossFit are good for our physical fitness but poor for building muscle.)

The goal is to find that happy middle ground where our sets of deadlifts are metabolically taxing, but not so taxing that they interfere with our ability to stimulate muscle growth. So when deadlifting for muscle size, we usually want to program sets of 5–8, occasionally dipping down to heavier sets of 3–4 or reaching up to sets of 9–10.

- Sets of 3–4: ideal for gaining strength, good for gaining muscle.

- Sets of 5–8: ideal for gaining strength and size, good for improving our cardiovascular fitness and work capacity.

- Sets of 9–10: ideal for gaining size and improving work capacity, but can be quite fatiguing for stronger guys.

When deadlifting for muscle size, we want to aim for heavy (3–5) and moderate (6–10) rep ranges, ideally becoming good at doing both. You might want to spend one phase focusing on volume and work capacity (8–10 reps), another phase focusing on pure hypertrophy (5–8 reps), and then a third phase focusing more on strength (3–4 reps).

How Many Sets of Deadlifts Should You Do?

The final thing to consider when using the deadlift for muscle growth is that although it stimulates more muscle growth per set than any other lift, it’s also disproportionately fatiguing.

What I mean is this:

- Doing three sets of deadlifts will build more muscle than doing three sets of any other lift.

- Doing three sets of deadlifts is a fairly fatiguing way of stimulating that amount of muscle growth.

Put another way, deadlifts are incredibly efficient per set (a high magnitude of hypertrophy stimulus), but also kind of inefficient per unit of fatigue (a lower stimulus-to-fatigue ratio).

For those of us who only have time to do a few short workouts per week, that’s no problem. We can just plough through our deadlifts. We won’t accumulate too much fatigue because we aren’t spending that much overall time or energy lifting weights.

But for those of us who lift hard, who lift often, or who are already managing higher levels of stress, we need to be mindful of the fatigue we’re accruing when deadlifting. While most people can get away with squatting a few times per week, attempting the same thing with deadlifts will often leave people feeling worn down.

There are a couple of rules of thumb that can help keep deadlifts from being overly fatiguing:

- Keep your back within the neutral range, limiting the stress on your spine—one of the main reasons that deadlifting can be so fatiguing.

- Stay at least a couple of reps away from technical failure (most of the time). The closer we go to failure, the lower the stimulus-to-fatigue ratio becomes. If we stay 2–3 reps shy of failure while deadlifting, we’ll get almost all of the muscle growth as if we went to failure, but not nearly as much fatigue. (Note that “failure” on a big compound lift like the deadlift occurs when our form starts to break down, not when we fail to lift the barbell. If our backs are coming out of the neutral range, then that counts as failure, and we want to stop our sets before that happens.)

In addition to that, though, we can also keep our fatigue in mind when programming deadlifts into our hypertrophy routines:

- Deadlifting once per week is usually enough to get great muscle growth, and doing just 3–5 sets is often fine.

- We can use plenty of secondary exercises to boost the volume on our target muscles much higher: Romanian deadlifts, split-stance Romanian deadlifts, good mornings, Zercher squats, barbell rows, and so on.

- If we’re struggling with fatigue, there’s no harm in taking a break from conventional deadlifts and switching to a variation that’s easier to recover from, such as Romanian deadlifts.

Deadlifts stimulate a tremendous amount of muscle growth, but given how many adaptations we’re provoking—bigger muscles, denser bones, stronger tendons, tougher palms, and better cardio—deadlifts are also quite fatiguing. It’s often best to keep our deadlift volume low while adding in plenty of volume from assistance lifts.

Summary

Deadlifts are great for bulking up the hips, hamstrings, spinal erectors, and upper back, and are arguably the single best lift for stimulating overall muscle growth. But they’re also hard, heavy, and fatiguing. They’re best used sparingly, especially if your lower back strength is a limiting factor.

When we’re deadlifting for hypertrophy, here are some good rules of thumb:

- It’s important to keep our backs within the neutral “range” to reduce shear stress and to minimize our risk of injury.

- Conventional deadlifts are the best default deadlift variation for bulking, given that they’re heavy, they’re great for bulking up our backs, and they use a large range of motion.

- When we’re deadlifting for muscle growth, we should use a similar tempo to our other bulking lifts: accelerate the bar as we lift it, and then set it slowly and gently back down.

- If we can maintain our positions while lowering the barbell, we won’t need to reset between reps. And if we’re setting the barbell down slowly, we won’t need to worry about bouncing.

- Deadlifts are fatiguing, so it often helps to keep our weekly deadlift volume low, and then to bring in the extra volume with plenty of assistance lifts.

Alright. That about does it. If you haven’t gained your first 20–30 pounds of muscle yet, or if you aren’t confident in your deadlift technique, then you’ll love our Bony to Beastly Bulking Program. We’ll show you how to build muscle and master the big (and small) lifts, as well as teaching you everything you need to know about the bulking diet and lifestyle.

If you’re already know how to lift weights and how to build muscle but you’re interested in min-maxing your bulking routine, or you’re running into size and strength plateaus, then you’ll love our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program.