How to Avoid Getting Sick While Bulking

Most of us know that working out, eating a good diet, and getting plenty of good sleep will improve our health. So why, then, whenever we start working out, do we keep getting sick. Isn’t working out supposed to make us healthier? Is getting sick every time we try to bulk up just an unavoidable part of our skinny curse?

Nothing can ruin the momentum of a good bulk like getting a cold, the flu, or—every skinny guy’s worst nightmare—the stomach flu. I can’t tell you many dozens of pounds I’ve lost to the stomach flu over the years. Getting sick while leading a sedentary life is bad enough, but it feels all the worse when we’re in the middle of a bulking routine. We lie there in fear, breathing through our mouths, certain that our muscles are being eaten away, but unable to muster the willpower to shovel down enough food to maintain our body weight.

Our bulks eventually resume, those pounds come back, and regaining muscle is a total breeze compared to gaining it in the first place. But still, better to never get sick in the first place.

Nothing will guarantee that we won’t get sick, but there are a few things we can do to reduce our risk.

Disclaimer: Marco has a health science degree (BHSc) from the University of Ottawa and is a certified personal trainer (PTS) and nutrition coach (PN). Even so, we aren’t doctors, and our intention here isn’t to say anything novel. Our goal is merely to gather and pass on the practical recommendations from qualified medical experts.

Why Do We Get Sick While Bulking?

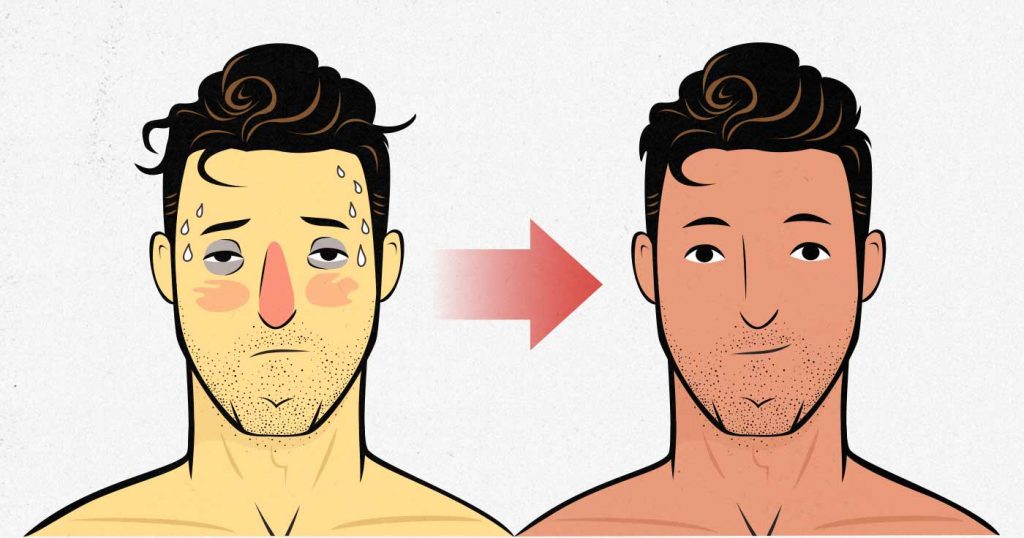

There’s a counterintuitive thing going on here. Working out causes stress, which forces us to adapt by growing bigger, stronger, healthier, and better looking—all great things. However, there’s that brief interval after working out where we haven’t recovered from the stress yet, and thus leave ourselves more vulnerable to getting a cold (or whatever). Or at least that’s what conventional wisdom tells us.

This idea of our immune systems being impaired after working out started in the 1980s when studies started coming out showing that running marathons raised the runners’ chance of getting sick. However, recent research by John Campbell, professor of health science at the University of Bath in England, found a problem with those studies: the runners were self-reporting their sniffles. Bath’s follow-up research found that most of the runners weren’t actually getting sick. Rather, running 26 miles had irritated their airways. They had sore throats, yes, but it was from all the huffing and puffing, not because they had gotten sick.

This led to a stream of new research which found that marathon runners actually had superb immune systems, presumably from being in such great shape, and thus got getting fewer colds than average. This advantage likely extends to less extreme training, too, with rodent research showing that even casual exercise leads to a greater chance of surviving violent strains of the flu.

However, researchers also discovered something they called the “open window” theory. The idea was that strenuous workouts could temporarily deplete our immune systems as we recover and adapt from the stress of training. By the time we’ve adapted, our immune systems are stronger, and so there’s no doubt that regular exercise winds up being a net benefit in the longer term. Even so there was quite a lot of controversy about whether beginners who start exercising for the first time are more vulnerable to getting sick in the hours following those first workouts.

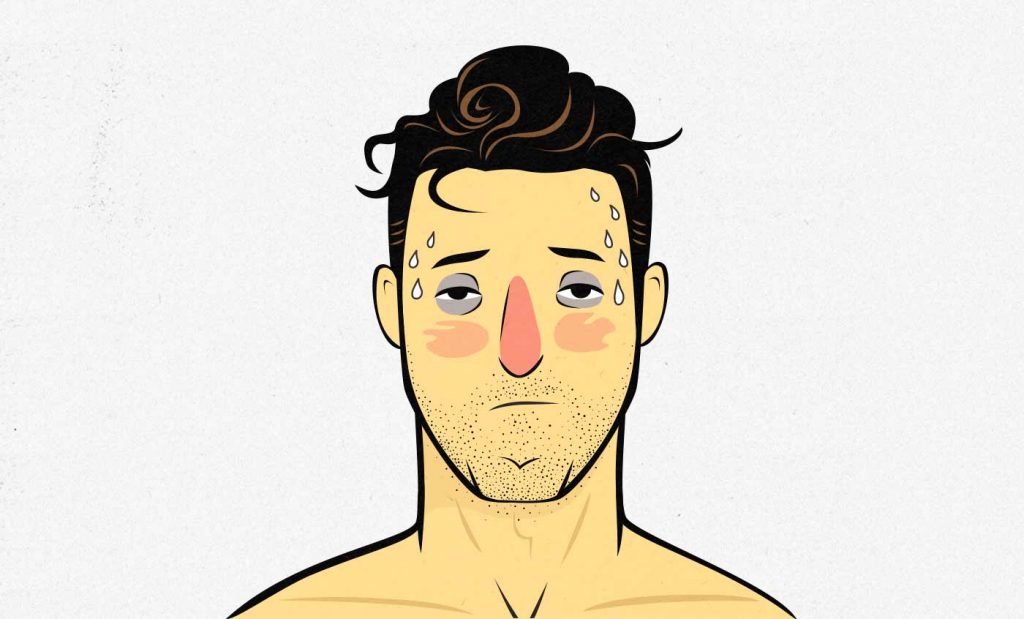

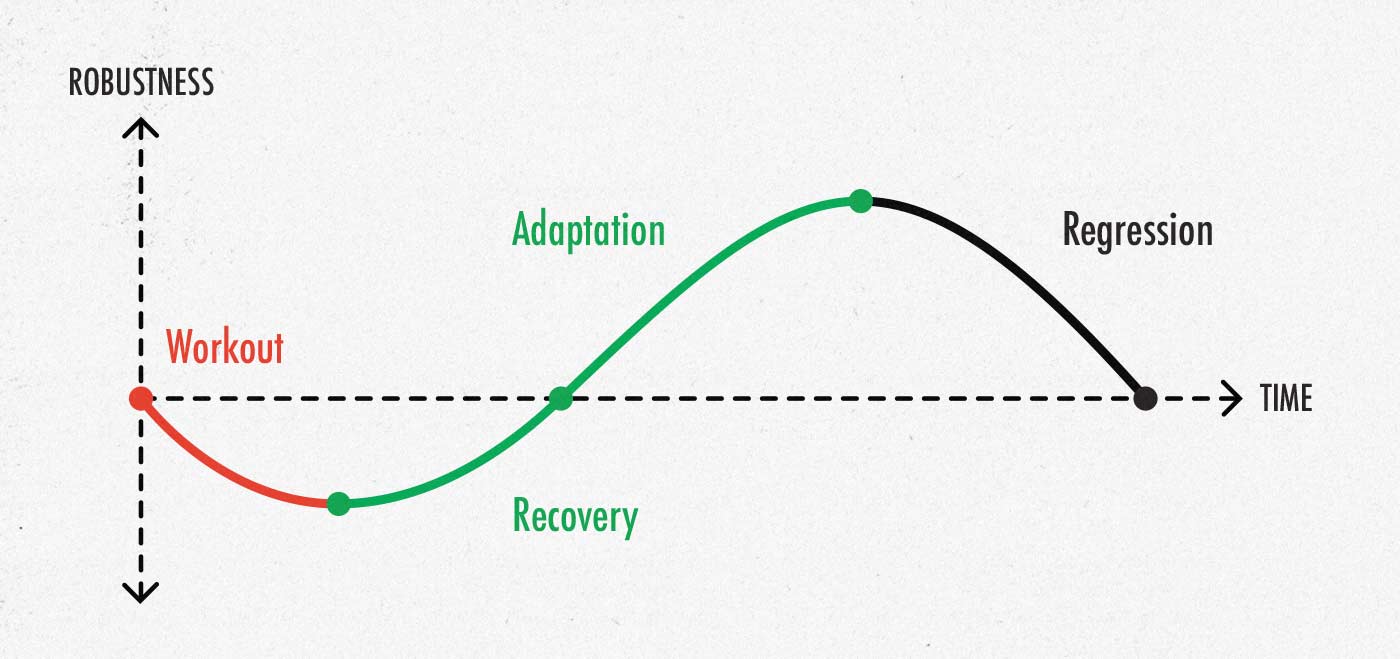

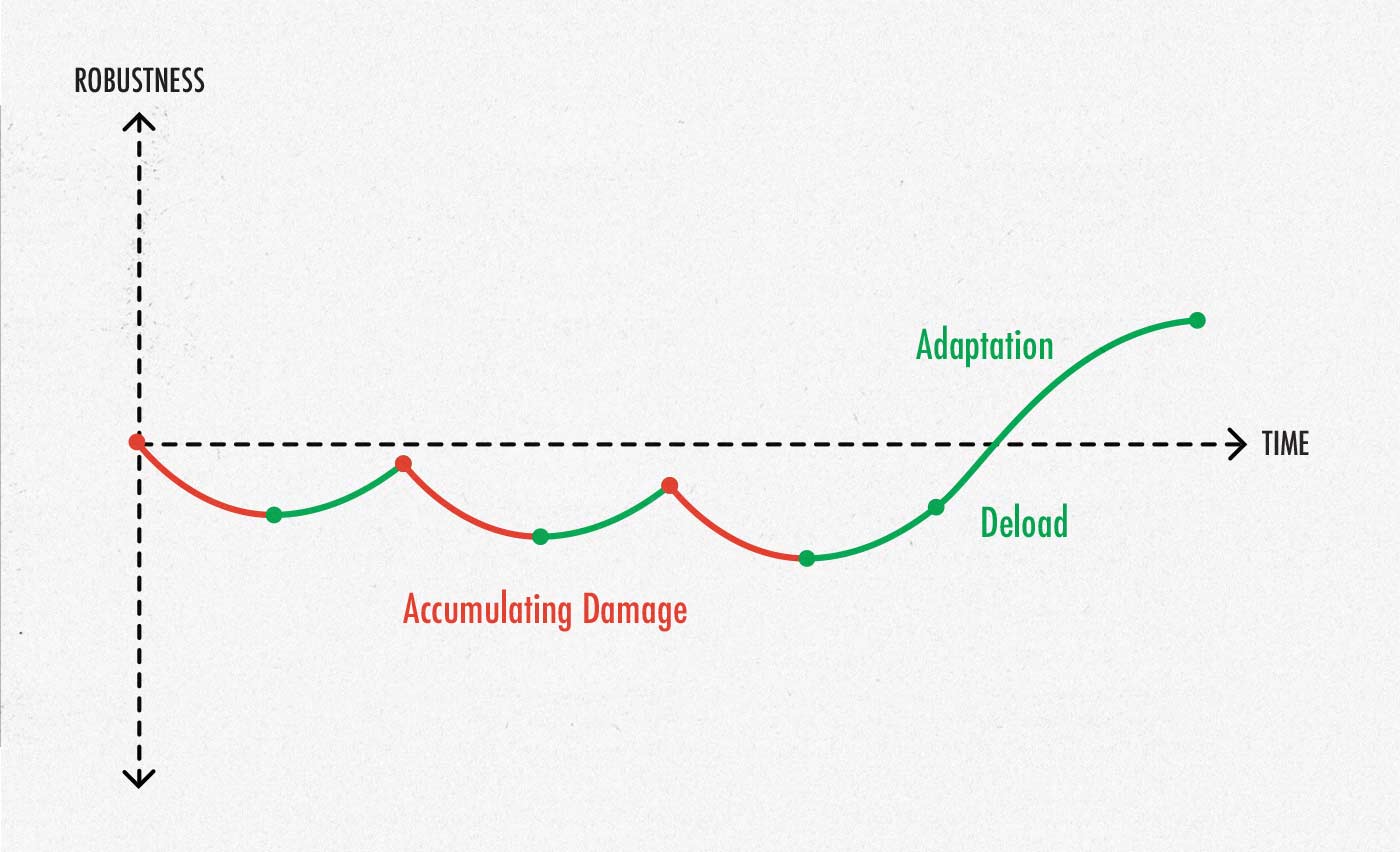

This gives us something called a stimulus, response, adaptation curve, usually shortened to simply SRA curve. What we see here is that we’re temporarily weaker after our workouts (recovery), but then grow more robust with time (adaptation). If we stop training, of course, then that adaptation disappears (regression). But the whole point of working out is to stack our workouts together to give us cumulative improvements, like so:

This is why marathon runners get fewer colds than the average person—because even if their immunity takes a hit from a hard training session, it’s still much higher than average. This was confirmed with the latest rodent research, showing that fit rodents have stronger immune systems than sedentary ones, even immediately after strenuous workouts.

Unfortunately, if this model applies to our immune system, then it would mean that someone who’s new to working out might briefly go through a period of getting sick more often. However, as we mentioned above, this is still quite controversial, with contemporary research showing that even beginners see enhanced antibacterial and antiviral immunity immediately after training (study).

Now, so far we’ve been talking research looking at people running marathons, which is quite extreme. Is this open window theory applicable to guys who are lifting weights a few times per week? Sort of. It’s more the professional powerlifters, bodybuilders, and athletes who run into problems from their far harder training. This is often because they’re doing multiple rigorous workouts per day, and sometimes with a heavily restricting calorie intake. Moreover, their careers depend on steady training, so even if they get sick less often than average, they may still want to reduce their risk even further.

So what does this mean for us? It means that a good bulking program probably isn’t intense enough to cause any immune problems, and should, in theory, lead to immunity improvements right from the very first workout, especially if we ease into our training somewhat gradually.

In fact, the average person is at greater risk of getting sick not because they’re exercising too much, but because they aren’t exercising enough. If we’re out of shape, we don’t have the robust immune systems of those who’ve been exercising for a solid decade. So as we fight to improve our long-term health, we may as well also implement some habits that will help keep us from getting sick in the short-term. Otherwise, we may get sick at similar rates to other sedentary people—a few colds per year.

Some of these habits that help us avoid getting sick go hand-in-hand with bulking, anyway. Eating tons of good food greatly improves our ability to recover from our workouts, as does making sure to get plenty of good sleep each night. If we’re eating and sleeping big while following a sensible bulking program, we should be able to lower our risk of infection in both the shorter and longer terms.

Should We Lift Weights While Sick?

The short answer is nope, don’t do it. Especially if we train at a public gym, where we’d be risking making everyone else sick. We ought to think of our fellow bulkers. If we can’t be gaining, at least they can. But even if we train at home, it’s still best to wait until we’re fully recovered before we start training again.

The long answer is, it depends on your symptoms are. Some experts, such as the researchers who conducted this study, recommend using the “above the neck” rule, where it’s okay to exercise if our symptoms are exclusively above the neck: a sore throat, an earache, a stuffy nose, and so on.

If all we have is a mild cold, we may not need to completely avoid exercise. To quote the experts at the Mayo Clinic, “Mild to moderate physical activity is usually OK if you have a common cold and no fever. Exercise may even help you feel better by opening your nasal passages and temporarily relieving nasal congestion.”

Unless you’re feeling like a train wreck I always recommend low intensity, low heart rate “cardio” during the first few days of sickness. Generally I prefer 20-30 minute walks done either outside (in the sunshine) or on a home treadmill (if you can’t get outside).

Dr John Berardi, Precision Nutrition

Furthermore, some symptoms persist even after our immune systems have already vanquished a virus. For example, it’s common for people to produce extra mucus after they’ve fought off a cold. That extra mucus then drips into our throats, giving us a lingering cough. Or maybe the extra mucus makes us breathe through our mouths while we sleep, giving us a sore throat. So some of these “above the neck” symptoms can occur even when we’re no longer sick. In that case, there’s likely no harm in exercising, and we may even be able to get away with jumping back into lifting weights.

To make things even more confusing, as with the marathon runners from earlier, it’s common to confuse the soreness and inflammation from lifting weights with being sick. A couple of days after doing neck curls for the first time, oi, those sore muscles in the front of our necks can really feel like having swollen lymph nodes. It’s also common to confuse allergies for catching a cold. As a result, especially when our symptoms are quite minor, we don’t always want to jump right to thinking that we’re too sick to lift, let alone to do any exercise at all.

On the other side of the spectrum, some symptoms, such as nausea, aches, fever, diarrhea, and phlegmy coughs are more indicative of a battle that’s still raging, and so we don’t want to add more stress into that mix. Better to not even dream about lifting until our symptoms move above the neck.

Now, even once we’re cleared to exercise, that doesn’t necessarily mean we want to jump back into lifting hard and heavy. Going for a walk outside in the sun and getting some blood flowing can be a good way to ease back into exercise when you’re still kind of sick and not quite ready to lift weights yet.

Finally, when we do go back to lifting weights, it’s best to start with a “deload” week—a week of easier training—as we’ll discuss below. We’ll be sensitive to the stimulus of lifting weights (and might have some lost muscle to regain), so even those easier workouts will be more than enough to stimulate muscle growth.

Losing Weight While Sick

As a general rule, eating enough food to at least maintain our body weight tends to be good for our health and immune systems. Strenuous strength training and bodybuilding workouts tend to combine well with abundant diets that are rich in whole foods, protein, and calories. If you’re worried about getting sick, it’s not the best time to embark on an ambitious cutting diet. Better to focus on building muscle.

However, our appetites usually do a pretty good job of telling us how many calories we need to maintain our health and immune systems (study). That’s what our appetite is for, after all. It’s not here to help us bulk up, but it is there to help us stay healthy. If you’re trying to build muscle, extra calories are certainly helpful, but even just eating in line with our appetites should be enough to reduce our risk of getting sick.

The same holds true if we get sick. If our appetites disappear when we get a fever, that can be a sign that our bodies don’t need an influx of calories right now (study). Even if our appetites have disappeared, though, it may still help to eat plenty of protein to reduce the amount of muscle mass that we lose as we inevitably lose weight overall.

Finally, I know it’s hard for us hardgainers to gain weight, and that losing weight while sick can be heartbreaking. But the last thing we need while trying to recover is to stress about losing weight. Building muscle is hard, but rebuilding it is quick and easy. There’s no need to stress about losing muscle while sick. Just focus on getting better.

How to Get Sick Less Often

There’s nothing we can do to eliminate our risk of getting sick, but there are some well-established guidelines that have been shown to help. If we look at the recommendations of Neil P Walsh from the European Journal of Sport Science, we get the following list (study):

- Try to avoid sick people, especially in the fall and winter.

- Ensure good hygiene and proper vaccination.

- Avoid touching the eyes, nose, and mouth.

- Don’t lift weights with “below-the-neck” symptoms.

- Try to keep chronic stress low.

- Carefully manage training stress.

- Replace overly long lifting sessions with shorter sessions.

- Deload more frequently, such as every second or third week.

- Aim for at least seven hours of good sleep every night.

- Eat a well-balanced diet and avoid losing weight.

Let’s go over some of these points in more detail.

Basic Gym Hygiene

No real secret that gyms have a bunch of germs, sweat, and tears in them, but there’s also research to prove it. That isn’t necessarily a problem, but again, there’s a temporary period right after hard training when our immune systems are slightly suppressed.

The worst thing we could do is avoid going to the gym. We’d be temporarily avoiding germs while missing out on the long-term benefits that come from growing bigger, stronger, fitter, and healthier. But we can also practice the basic hygiene that the CDC recommends:

- Stop touching your face (and picking your nose).

- Wash your hands after lifting weights.

Not rocket science, and it should significantly reduce your risk of getting an infection.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. If you build yourself a home gym, does that mean you get to pick your nose? I can see an argument for that, certainly, but it’s still probably best to practice good hygiene.

Don’t Train Too Hard Too Early

Lifting weights hard enough to provoke muscle growth will cause stress. That’s a good thing. That’s how we build ourselves stronger, tougher bodies and immune systems. However, more stress isn’t always better.

For new lifters, remember that as we lift weights, we adapt by growing both stronger and tougher. That means that when we first start lifting weights, we aren’t very tough yet. That’s an adaptation we make over time.

Going back to John Campbell’s immunology research, he says, “If you have not been exercising, now might not be the ideal moment to start an extremely ambitious and tiring new workout routine.”

For beginners, it’s often best to start with fairly low training volumes—just a couple sets per exercise—and then gradually work our way up. That will ward off the crippling soreness, it will be easier on our immune systems, and it will still be enough to provoke muscle growth, so we aren’t losing anything.

For seasoned lifters, have you ever taken a break from lifting weights, gotten a bit detrained, and then gone back to lifting? Your habitual workout routine probably destroyed you, leaving you miserably sore for days at a time. That’s because your body lost some of those beneficial adaptations. Those adaptations will come back, but it’s better if we ease back into it.

For those of us who are detrained and just getting back into lifting weights again, it’s often best to start with just a couple sets per lift. That will be enough to stimulate muscle growth without totally destroying ourselves, and as we recover and adapt, we’ll earn back our ability to train with higher volumes. The next week, we can add another set to each lift. The week after, we can add another. Within a month, we’ll be back to our higher training volumes, and we’ll have made solid gains along the way.

We Don’t Need to Train to Failure

To build muscle, it’s true that we need to challenge ourselves. If we lift too far inside of our means, then there’s no need to adapt: we’re already strong enough. So we need to lift close to failure while trying to build muscle.

However, we don’t need to lift all the way to failure. Stopping 1–3 reps short of failure when doing hypertrophy training produces just as much muscle growth as lifting all the way to failure. This is important because stopping even just a couple of reps shy of failure imposes significantly less stress on our systems, and can reduce the amount of time it takes to recover between workouts by as much as 50%. This is especially important with the big compound lifts.

That isn’t to say that we should never train to failure, but we might want to leave a couple of reps in reserve by default, only going near failure when we have a good reason to. For example, we might want to take our final sets to failure sometimes just to make sure that we aren’t leaving too many reps in reserve. This can be especially important for beginners who are trying to learn what it feels like to stop just shy of failure.

We may also want to go all the way to failure on the final sets of our isolation exercises. The risk of injury is low and smaller lifts are fairly easy to recover from anyway. But that’s a far cry from taking every single set of every single exercise to failure every single workout, and so it should dramatically reduce the amount of stress we need to manage.

Take Breaks Before Fatigue Accumulates

Our muscles recover pretty quickly and easily. They’re designed to adapt based on the demands we face. That’s why building muscle works so incredibly well. This means that so long as our training program is reasonable, our muscles shouldn’t have much trouble recovering between our workouts, especially if we’re resting a day or two between workouts. Great.

Furthermore, lifting weights stresses our cardiovascular systems. So much so that lifting weights for an hour counts as doing thirty minutes of dedicated cardio. Like our muscles, our cardiovascular system can recover and adapt quickly. Also great.

However, when we’re lifting weights, we’re not just stressing our muscles and cardiovascular systems. We’re also stressing our connective tissues and loading up our bones with tons of weight. This is good too, of course, but it also complicates things. Our bones and connective tissues have different recovery curves from our muscles. They can take weeks to heal instead of days. So as we do workout after workout, sometimes the stress on our overall system can accumulate. Eventually, it reaches a breaking point and we get injured, demotivated, or even catch a cold.

One way to get around this is to schedule “deloads” where we intentionally train with a lower volume, with a lower intensity, or we stop our sets further from failure—perhaps all three. This ensures that we aren’t accumulating stress, and that every new phase of our training starts off from a fully recovered baseline.

There’s some debate about how often to schedule deloads. Serious athletes who are doing several hours of intense training every day may benefit from deloading quite frequently, which is why the European Journal of Sport Science recommends deloading every 2–3 weeks. However, few of us are serious athletes, and most of us are only lifting weights for a few hours every week. We accumulate fatigue less quickly, and so it may be best to deload every 4–7 weeks instead, giving ourselves longer to provoke muscle growth between our breaks. If you’re particularly worried about getting sick, though, or if you’re starting to feel worn down, then there’s no problem in deloading more often.

The good news about deloads is that even if we take a week completely off from working out, most research shows that it wouldn’t even slow down our muscle growth. Let me repeat that: even if we take a week completely off from lifting, we still build muscle at the same overall pace.

Mind you, if we take a week off from training, we’d lose some of the toughness we developed, and we’d need to deal with greater amounts of soreness when we return to our workout programs. We’d also risk falling out of the habit of lifting. For those reasons, it’s usually better to do a proper deload week. But still: no harm in breaks.

Live a Generally Healthy Lifestyle

When we’re sick, there’s not a lot we can do. We can try to eat the proper amount of protein and try to avoid falling into too deep of a calorie deficit. But once we’re already sick, the main thing is just to wait it out, get better, and then go back to working out afterwards. We just have to chill out (literally, sometimes) and be patient.

If we’re repeatedly getting sick, though, we might want to see if there’s something we can do to improve our general health. It’s not that we can necessarily “boost” our immune system, but rather make sure that it has everything it needs to function properly. There are a few things that have been shown to help:

- Getting more good sleep. At least a couple of studies show that getting enough sleep reduces our risk of getting sick (study, study). Sleep is an important part of maintaining good health and immune function, and when we’re lifting hard, eating big, and making a massive renovation to our physiques, it only becomes that much more important. For more, we’ve got an article on how to get better sleep while bulking over on Outlift.

- Reducing chronic stress. Being chronically stressed in our day-to-day lives can interfere with our hormones and our ability to recover from hard training. There’s no single solution that works for everyone, but anything that minimizes our chronic stress can help (such as meditation or prayer, joining a community, reading fiction in the evening, etc).

- Eating more whole foods. Part of having a robust immune system is eating enough fruits, veggies, and whole foods in general. Aim for 5+ servings of fruits and veggies per day, and try to get at least 80% of your calories from minimally processed foods. There are plenty of great bulking foods that are nutritious while still making it easy for a skinny hardgainer to eat enough calories to gain weight.

- Checking for micronutrient deficiencies. Some nutrients seem to have a bigger role in building a strong immune system than others. Having around a clove of garlic every day, for example, seems to reduce the incidence of illness. So does having enough vitamin C. And it’s important that you aren’t deficient in iron or zinc. For more, Examine has a good article about which supplements can help with colds and the flu.

- Eating more probiotics. Recent research shows that having probiotics in our diets, such as those found in yogurts, hard cheeses, kefir, Yakult, kimchi, and sauerkraut, can help reduce the incidence of illness while lifting hard.

- Getting daily sunshine. Getting enough sunshine every day allows us to produce enough vitamin D, which helps regulate immune cells during infections. This could be as simple as taking a walk in the sun every morning or going outside for lunch (even in the winter). If that’s not realistic, there’s a 2017 meta-analysis showing that supplemental vitamin D also reduces the risk of getting respiratory tract infections.

These general lifestyle habits aren’t just good at improving our immune systems, they’re also habits that will help us train harder, build more muscle, and gain more strength.

Key Takeaways

Regular exercise can improve your immune system and general health over time. However, if you’re a beginner, there’s some controversy about whether a hard workout could make you more vulnerable to getting sick. Most modern research suggests that beginners do just fine, though, even if the workout is rigorous (study).

What’s clear, though, is that as the benefits of exercise accumulate, your immune systems will grow quite a bit stronger, leading to several general health benefits:

Evidence from epidemiological studies shows that leading a physically active lifestyle reduces the incidence of communicable (e.g. bacterial and viral infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g. cancer), implying that immune competency is enhanced by regular exercise bouts.

John P Campbell and James E Turner, Department for Health, University of Bath.

Even so, keep in mind that regular exercise merely reduces your risk of getting sick. It doesn’t eliminate the risk entirely. Most people get a few colds per year. By exercising, maybe you drop that down to just a couple. If you can drop that even lower by making some improvements to your diet, exercise routine, and lifestyle, even better.

The first thing you can do to reduce your risk of getting sick is to practice good basic hygiene, especially in the gym:

- Stop touching your face (and picking your noses).

- Wash your hands when you leave the gym.

There are also a few things you can do to make your training less stressful while still provoking an optimal amount of muscle growth:

- Gradually work your way up to longer, harder workouts.

- Leave a couple of reps in reserve on most sets most of the time.

- Take an easy deload week every few weeks to reset your recovery back to baseline.

Finally, you can try to improve your overall lifestyle:

- Get more good sleep.

- Reduce your chronic stress.

- Eat more whole foods, including eating enough garlic, vitamin C, iron, and zinc.

- Include probiotics in your diet—foods like yogurt, hard cheese, or sauerkraut.

The good news is that regular exercise, eating a good bulking diet, and getting plenty of sleep all have positive effects on both your general health and immune system. You’re already on the right track.