DOMS: Is Muscle Soreness A Sign of Muscle Growth?

When I first started lifting weights, I was absolutely crippled by muscle soreness. I would wince when sitting in chairs, struggle to lift my knees high enough to climb stairs, and barely be able to get glasses from the cupboard. I loved it. I was sick and tired of being skinny, and I thought muscle soreness was a sign that my muscles were growing.

A couple of months later, my soreness faded away to almost nothing. I could sit down in a chair without everyone in the room grimacing. I could even hold myself upright in it. I started to feel less like a burning puddle of oil, more like a human being. It was awful.

My gains had started to slow down as well, and I was convinced that my waning muscle growth was connected to my fading muscle soreness. Was my fading muscle soreness causing my plateau?

Muscle soreness is intimately connected to muscle growth, but most have no idea how it works, making the process more confusing. So in this article, let’s go over a few of the more common muscle soreness questions that we get:

- What’s the link between muscle soreness and muscle growth?

- How much muscle soreness is good?

- Should you work out if you still feel sore from the last workout?

- Can muscle soreness interfere with muscle growth?

- What can you do to reduce muscle soreness?

- Can you build muscle without getting sore?

- What if a muscle never gets sore?

- What if your joints or tendons get sore?

- What if your lower back gets sore?

- What is Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)?

- Does Muscle Soreness Indicate Muscle Growth?

- Why Do Beginners Get So Sore?

- The Repeated Bout Effect (RBE)

- Should We Work Out If Our Muscles Are Still Sore?

- How to Lift With Sore Muscles

- What If We’re Still Sore After Warming Up?

- What If A Muscle Isn’t Getting Sore?

- How to Make Our Muscles Less Sore

- What If We Have Sore Tendons or Joints?

- What if We Feel Achy & Inflamed Overall?

- Should We Have a Sore Lower Back After Deadlifts?

- How Can We Build Tougher Lower Backs?

- How To Tell the Difference Between DOMS & A Back Injury

- What If Your Lower Back Is Always Sore?

- Summary

What is Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)?

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS): the soreness caused by weight training or other forms of exercise. Our muscles will likely feel the sorest 24–72 hours after lifting weights, but if your workouts are quite a bit more strenuous than you’re used to, the soreness can last up to a week (or more).

When you challenge your muscles with a workout they aren’t prepared for, you cause small-scale damage (microtrauma) to your muscle fibres. Your immune response will then slowly kick into gear, sending in blood and nutrients to repair the damage (acute inflammation), and causing your muscles to feel tender, stiff, and sore (study). The good news is that your muscles will often adapt by growing back bigger and stronger than they were before.

It’s worth noting that lowering a weight causes more damage to your muscles than lifting it. This means that if you focus on just the lifting portion (the concentric), as is done in Olympic lifting, then you won’t be causing much muscle damage, and so you won’t feel very sore afterwards.

However, if you emphasize the lowering portion of the lift (the eccentric), such as learning how to do chin-ups by jumping up to the bar and then slowly lowering yourself down, then you’ll cause quite a lot of muscle damage and soreness.

You shouldn’t base your style of training around muscle soreness. Instead, if your goal is bulking up, then you’ll want to use a proper lifting tempo for muscle growth, which will involve lifting explosively, accelerating the weight through the range of motion, and then lowering the weight down under control.

If the weight is light (8–20 reps), then you’ll be able to blast through those reps fairly quickly, which won’t cause much soreness. But if the weight is heavy (4–6 reps), it’s going to be much harder to accelerate as you lift the weight up, and when you lower it back down, you might need to do it quite slowly in order to maintain control. This slower, more grinding tempo can cause more muscle soreness.

A good hypertrophy training program that’s designed to stimulate muscle growth will emphasize both the concentric and eccentric parts of the lift and will prioritize the 6–20 rep range (with sets of 4–40 reps sprinkled in). As a result, it will probably make you quite sore, especially if you’re relatively new to lifting weights.

Does Muscle Soreness Indicate Muscle Growth?

No, muscle soreness doesn’t necessarily indicate muscle growth. Only certain types of exercise cause us to adapt by building bigger muscles, but any type of strenuous exercise can cause delayed onset muscle soreness. For instance, doing cardiovascular exercise can make our muscles quite sore, but cardio won’t cause a significant amount of muscle growth.

If you’re working out in a way that stimulates muscle growth, such as hypertrophy training, bodybuilding, strength training, or even CrossFit, then soreness tends to be a sign that you’ve caused enough stress to provoke an adaptation, but even then, there’s some nuance to it. Not all types of weight training are designed to stimulate muscle growth. A bodybuilding or hypertrophy routine is the most specific way to train for muscle growth, and so soreness from doing those workouts is most strongly linked to muscle growth.

Why Do Beginners Get So Sore?

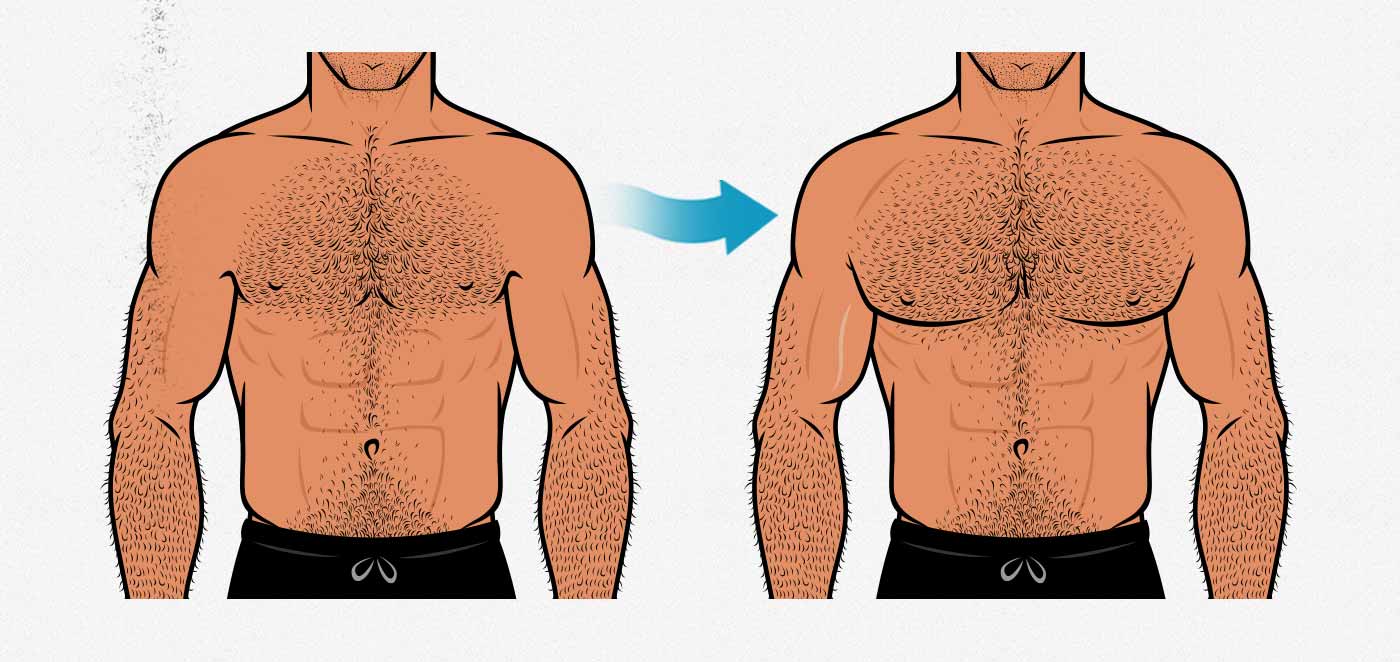

Beginners haven’t developed much muscle toughness yet, which can make them vulnerable to extreme amounts of muscle soreness. Beginners can also build muscle very fast (i.e. newbie gains). This means that when a beginner is feeling most sore, he may also be experiencing the most rapid muscle growth. Then, as he gains experience lifting weights, the soreness will fade and his rate of muscle growth will slow. This makes it seem like soreness is an indicator of muscle growth. But there are a few problems with that assumption.

The more muscle damage we cause, the more resources need to be invested in repairing our muscles. But we aren’t interested in muscle repair, we’re interested in muscle growth. This is an important distinction to make because there’s some research showing that more resources being invested in muscle repair leave fewer resources available for muscle growth. This makes sense intuitively, too. Better to spend our time building new muscle instead of just repairing the damage we’ve caused.

Besides, excessive damage and soreness drastically extend the recovery process, preventing us from stimulating new waves of muscle growth as frequently. For instance, most research shows that our muscles grow best if we train them 2–3 times per week, but if our workouts are making us sore for several days, then we might find ourselves delaying our training, and thus missing out on opportunities to trigger new waves of muscle growth.

The Repeated Bout Effect (RBE)

The repeated bout effect: when we lift weights, it stresses our muscles, causing our muscles to adapt by growing bigger, stronger, and tougher. This toughness reduces the amount of stress of lifting weights, making it harder to provoke more adaptations.

Lifting weights doesn’t just make us stronger, it also makes us tougher. This toughness allows us to handle weights without sustaining as much damage. But new lifters haven’t developed any of this toughness yet, making them incredibly vulnerable to muscle soreness.

As a result, it’s usually better for beginners to ease into weight training slowly, doing enough work to stimulate muscle growth while minimizing the amount of stress and muscle damage. This reduces soreness and speeds up muscle growth. Some muscle soreness is to be expected (and is a good sign) but it shouldn’t be a crippling amount of soreness. If the soreness makes it hard to walk or move your arms, or if you aren’t able to lift as much weight in your next workout, then it’s a sign that we’ve caused excessive damage.

Mike Zourdos, PhD, recommends beginning each training phase with some intentionally easier training. Enough to cause maximal muscle growth, but not so much that we cause excessive muscle damage. A recent study lends support to this idea, showing that we can protect ourselves from the stress of a hard workout by doing easier workouts beforehand.

In the Bony to Beastly Bulking Program, we do this by starting each phase with something called a deload week. These deload weeks have just two sets per exercise, and we recommend stopping each set two reps shy of failure. This frees up more time and energy to learn the new lifts, and it also reduces the amount of muscle damage you sustain, resulting in less muscle soreness and more muscle growth. Then, as you get deeper into your workout routine, you’ll develop more toughness, and you’ll thus be able to handle longer and more challenging workouts. This means that a good workout routine should start off fairly easy and then get progressively harder, keeping up with the toughness you’re developing, and always challenging your muscles just enough to provoke growth without causing excessive damage.

What’s interesting is that this toughness applies to the specific muscles being trained, but also to our entire bodies. If you build up a strong squat, for example, your legs will gain the most toughness, but your entire body will grow tougher, giving you the ability to withstand more stress without becoming sore or fatigued. This is why you’ll see advanced lifters being able to handle horrific workouts. They’ll take sets to failure, use cheat reps, do drop sets, and all kinds of insanity that would destroy a beginner or intermediate lifter.

Should We Work Out If Our Muscles Are Still Sore?

Yes, it’s usually okay to work out even if our muscles are still sore. However, if the soreness is intense enough that it’s interfering with our ability to train, it can be a sign that we’re causing too much muscle damage, and so we might want to ease into our workout routine a bit more gradually.

To build muscle, first we need to stress our muscles enough to stimulate muscle growth, then repair the damage we’ve caused, and then adapt by adding extra muscle mass. This process takes around 48 hours, at which point we can head back to the gym to stimulate a new wave of muscle growth. That’s why many good beginner/intermediate lifting programs will look something like this.

- Monday: Full-body workout

- Tuesday: Rest

- Wednesday: Full-body workout

- Thursday: Rest

- Friday: Full-body workout

- Saturday: Rest

- Sunday: More rest (Why? We’ll cover that below.)

As you can see, muscle soreness peaks 24–72 hours after training, but we have a workout scheduled every 48 hours. This means that if we have a typical recovery timeline, you should expect to be training with muscles that are at least somewhat sore.

That’s odd, right? If muscle soreness is linked to muscle damage, why would we want to work out while our muscles are the most damaged? But that’s not the case. Muscle damage is the highest right after we finish our workouts. Muscle damage is highest before the repair process begins. This is also when we experience the greatest loss of strength.

Muscle soreness, on the other hand, lags behind. In fact, by the time our muscle soreness is peaking, our strength has likely recovered (study). Furthermore, stimulating a new wave of muscle growth doesn’t seem to harm recovery (study), so lifting weights with sore muscles doesn’t seem to cause any problems.

How to Lift With Sore Muscles

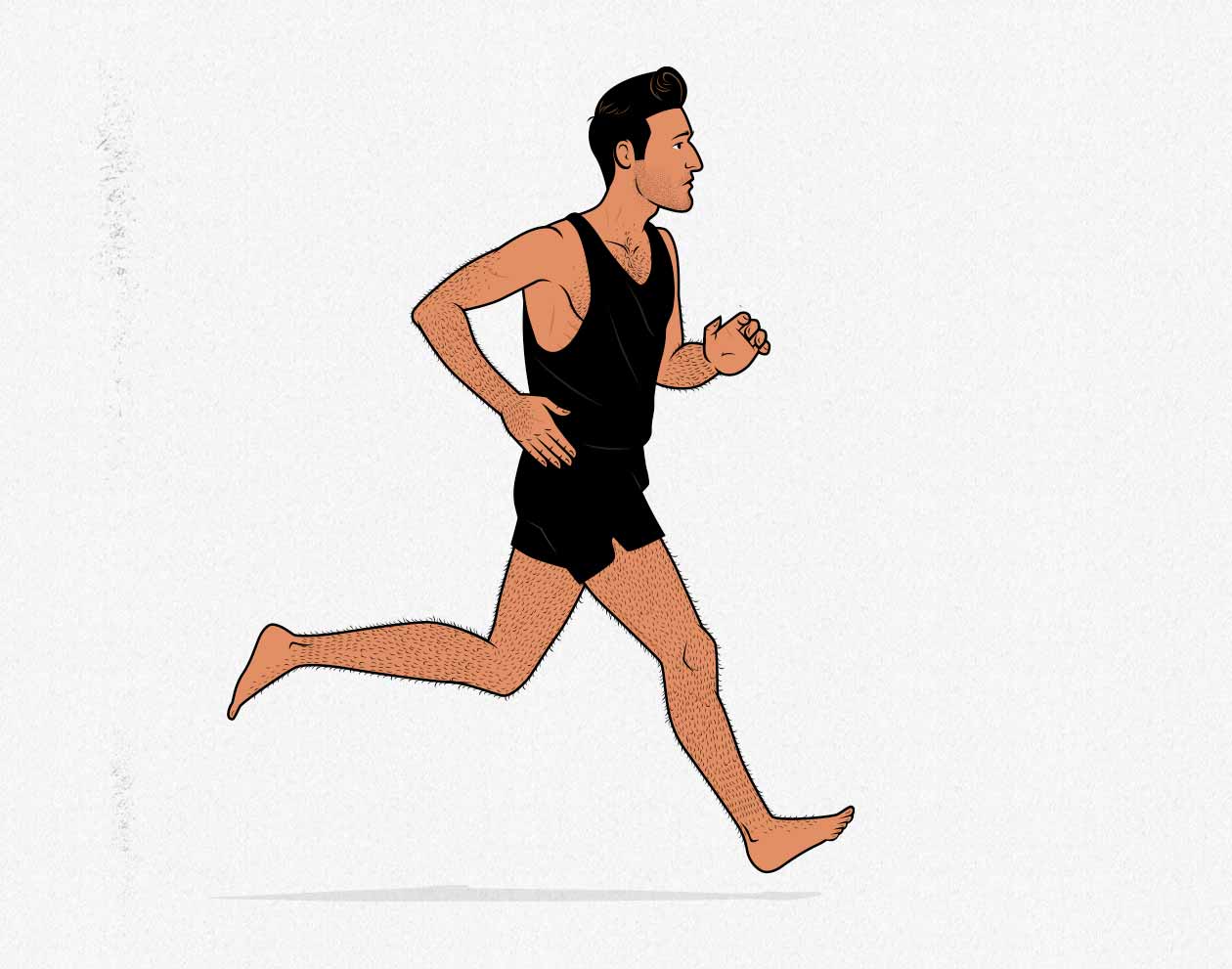

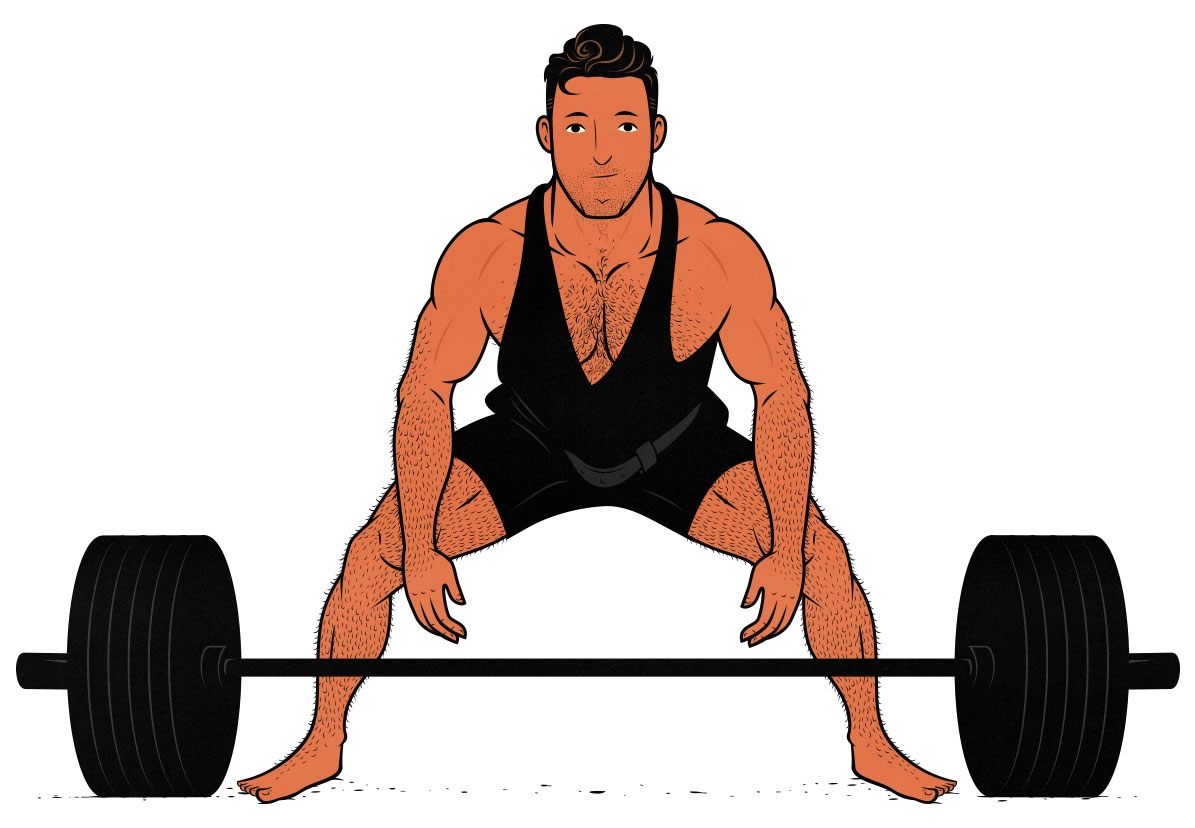

Even if you’re still feeling sore, you’re probably strong enough to stimulate a new wave of growth. The obvious problem with training while sore is that it hurts. A less obvious problem is that soreness makes your muscles stiffer, which can make it harder to do the lifts properly. You might find it harder to set up for a deadlift, sink deep into a front squat, and bring the barbell down to your chest during a bench press.

If you’re a beginner, your mobility and technique might still be pretty limited, making this an even bigger issue. The last thing we want to do is have you hobbling through a workout, lifting with poor posture, and risking injury.

The best way to prepare a sore muscle for heavy lifting is to do some dynamic warm-ups and then some light warm-up sets. That will get some blood flowing into the area, “warming it up,” which will reduce your soreness, reduce your stiffness, and thus reduce your risk of injury (study, study). By the time you finish your warm-up sets, your mobility should be restored, and you’ll probably feel ready to lift heavy.

What If We’re Still Sore After Warming Up?

Soreness is fairly subjective. Everyone has a different pain threshold (the point at which pain is felt) and a different pain tolerance (the amount of pain someone can bear), so the best way to figure out if you’re ready to lift weights again is to use something more objective: strength.

Do some dynamic warm-ups and light warm-up sets, then get under the bar to attempt a working set. If you’re a beginner, you should fully expect to be able to outlift yourself every workout, even if you’re sore. Some of that new strength will come from improved lifting technique (practice), some from improvements in coordination (neural gains), and some from gaining extra muscle mass. You’ve got three types of adaptation on your side, so always fight for progressive overload.

- If you’re stronger, great. Finish your workout and keep doing what you’re doing.

- If your strength is similar to before, that’s still okay. The fact that you’ve regained your strength shows you’ve recovered enough to stimulate a new wave of muscle growth. Ensure that the other aspects of your bulking routine are on point: enough calories to gain weight, enough protein to build muscle, and plenty of sleep. Try to show up stronger next time.

- If you’re weaker than you were last time, that’s a sign that your muscles aren’t ready yet. They’re still too damaged. If it’s discomfort and you can’t lift properly—with good technique and strength—your muscles haven’t recovered enough for heavy lifting.

If your muscles are still too sore to lift properly, we recommend doing some light sets for every exercise in your routine to get some blood flowing into your muscles. These light workouts are called “active recovery,” if your soreness is impairing your workout performance, it’s much better than simply resting. It will not only speed up your recovery from the previous workout, but it will also toughen your muscles in preparation for the next workout (study). Plus, it will help clear out the crippling muscle soreness.

Even if your entire workout is just warm-up sets, count the workout as complete and continue on with your workout program as planned. Make an effort to eat more calories, more protein, and get more sleep. Perhaps by the following week, you’ll be a little tougher, and the workout will go as planned. If not, you may need to adjust your workout routine: stop lifting so close to failure, do fewer sets per muscle group, and so on.

What If A Muscle Isn’t Getting Sore?

If some of your muscles are getting sore, but a specific muscle isn’t, as you may have feared, this can be a sign that you aren’t stimulating it properly. For example, let’s say that you’ve been doing the bench press, but you’re only feeling sore in your shoulders and triceps. This could be a sign that your chest isn’t a limiting factor, and you aren’t bringing it close enough to failure to stimulate muscle growth. In this case, if we don’t find a way to stimulate your chest, your chest may lag behind your other muscles.

However, don’t expect your muscles to all feel equally sore. For example, this study shows that your shoulders aren’t as prone to muscle soreness as your legs, meaning that if you wake up after doing a full-body workout and feel far more soreness in your quads than in your shoulders, that doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s an imbalance in your training.

On the other hand, most people choose lifts that challenge their shoulders in a contracted position (such as with lateral raises, overhead presses, and incline bench presses) instead of challenging them in stretched position (such as at the bottom of a close-grip bench press). We stimulate far more muscle growth if we challenge our muscles in a stretched position, and so if you aren’t able to make your shoulders sore, you might want to double-check that you’re giving your shoulders a good workout.

If a muscle isn’t feeling sore two days after a workout, what I’d recommend is that you start palpating—poke and prod your muscles, looking for any traces of tenderness. If there’s even the tiniest bit of soreness when you massage the muscle, you know that you’ve caused at least a little bit of stress. The degree of soreness isn’t linked to the degree of muscle growth, so that’s good enough. It’s only when you don’t experience any soreness in a muscle that I’d try to give it some extra love.

What should you do if a muscle isn’t getting sore? The first thing you can do is build redundancies into your workout routine. For example, we don’t rely on the bench press to build a big chest, we follow it up with some sort of chest isolation exercise, such as a chest fly (a controversial but effective lift). We also use a variety of other chest exercises, such as push-ups and pullovers.

You can also look into your lifting technique. Perhaps your grip is too narrow on the bench press, your arch is excessive, you aren’t clenching your shoulder blades down into your back pockets, or you aren’t bringing the barbell all the way down to your chest. A lack of soreness in your chest might be a sign that you should double-check your technique. There’s some genetic diversity here, though, so that might not completely solve the issue. (Here’s our program for guys with stubborn or lagging chests.)

How to Make Our Muscles Less Sore

Feeling sore can be a real bother. With a proper workout routine, it shouldn’t be too bad, but it’s common for beginners to overdo it in their first couple weeks of lifting. It’s also fairly common for guys to come back from a vacation, jump back into their lifting routine, and absolutely annihilate themselves. So what should you do if you’re being murdered by muscle soreness?

First of all, avoid taking anti-inflammatory pills such as Advil or Aspirin. If you take enough medication to reduce your muscle soreness, you’ll also be taking enough to blunt your muscle growth. After all, the soreness is connected to the recovery process. Inflammation is your body attempting to heal and adapt. We don’t want to dampen that effect, we want to enhance it.

Instead of trying to reduce inflammation, we want to do the opposite. We want to increase blood flow to the area. You could do this with a massage or a sauna, but a more effective way is to do some warm-ups followed by some light exercise. This will pump blood through your sore muscles, speeding up recovery and also reducing muscle soreness. This is another reason why scheduling your workouts right in your moments of peak soreness can be a benefit: it gets rid of the soreness!

What If We Have Sore Tendons or Joints?

As long as muscle soreness isn’t crippling, it’s often a good thing. But what about soreness in, say, your tendons? Or what about soreness in your knees or shoulder joints? First of all, it’s important to understand that lifting, especially if you’re lifting in lower rep ranges, is going to put quite a lot of stress on everything. Your bones, tendons, and even your heart are going to be stressed by heavy lifting. And again, just like your muscles, they’ll grow stronger, they’ll grow tougher, and they’ll even grow a little bit bigger. This is usually a good thing, but there’s a caveat.

There’s nothing wrong with stressing your bones, tendons, joints, and all manner of connective tissues, but if you’ve stressed them so much that you’re feeling soreness, it’s probably a sign that you’ve taken things too far. One of the first symptoms of your lifting program being too intense is that you start to notice sore tendons and cranky joints. You don’t just feel sore, you feel worn down; you feel old.

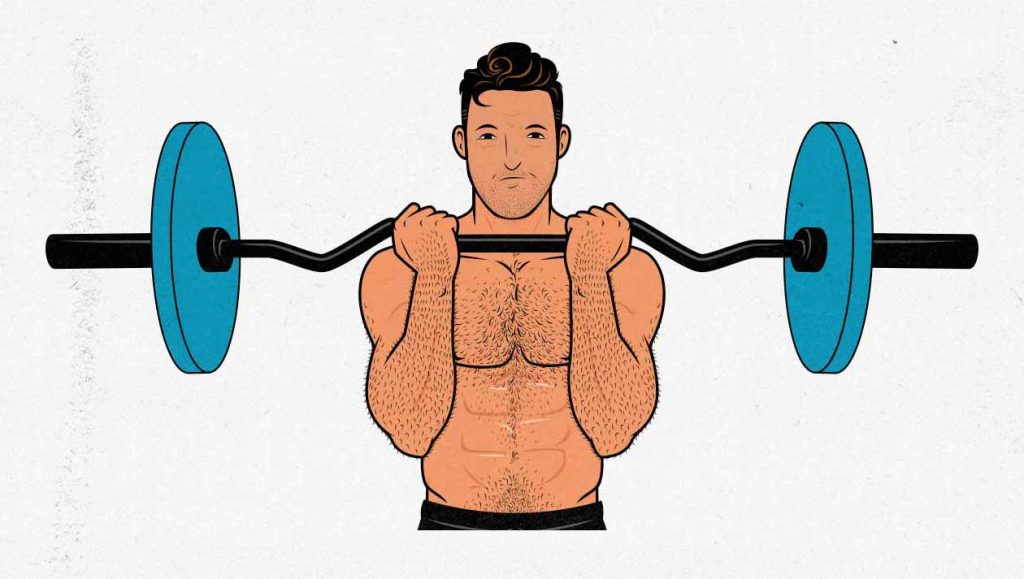

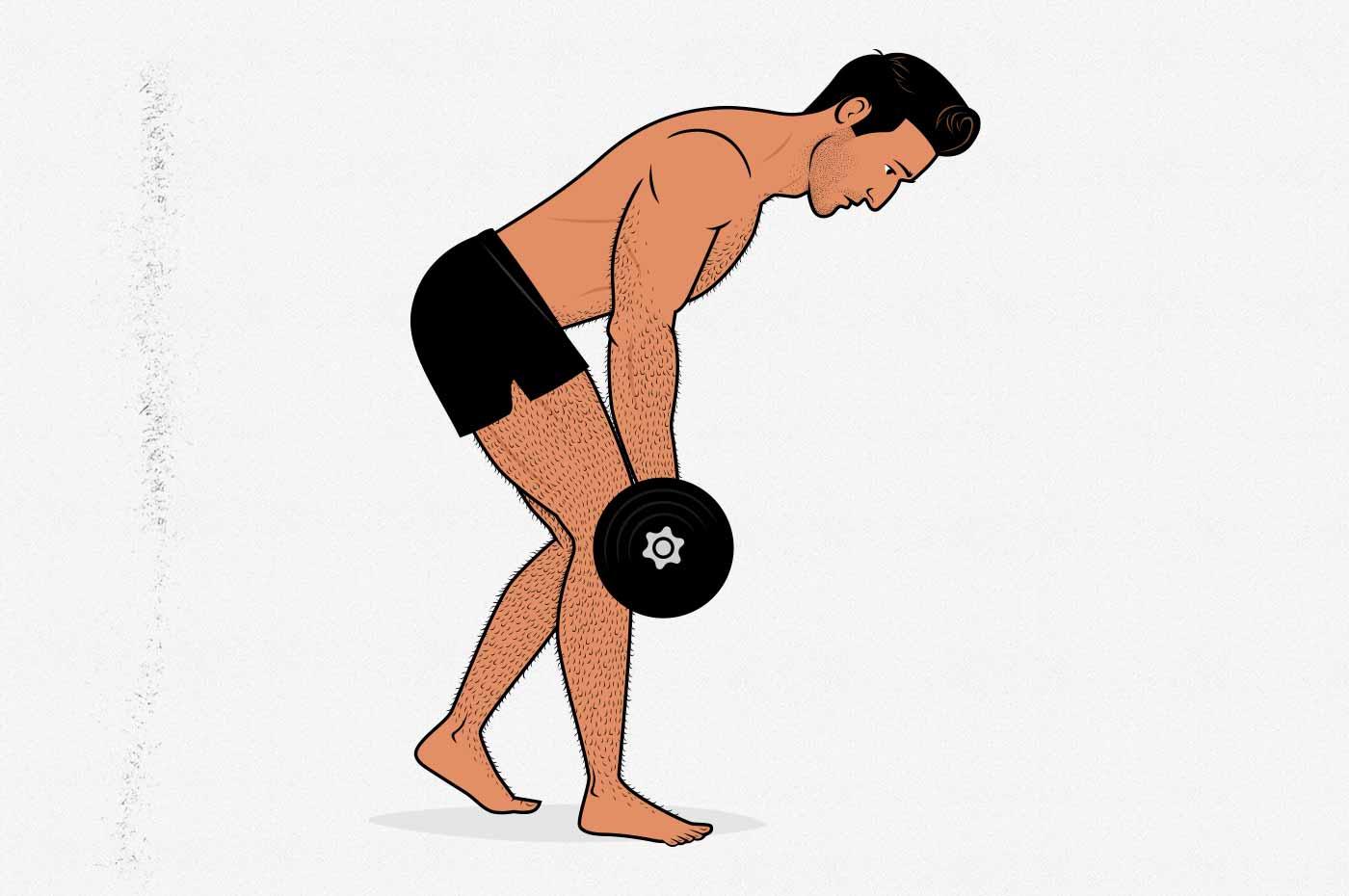

In some cases, the problem is coming from specific lifts. It’s common to get sore elbows when doing barbell curls, aching shoulders when doing the bench press, cranky hips when doing low-bar back squats, or a painful lower back when doing conventional deadlifts.

When that happens, choose different exercises that don’t bother your joints. If barbell curls or sissy curls make your elbows ache, switch to using a curl bar (aka EZ-Bar) or dumbbells. If the barbell bench press hurts your shoulders, try dumbbells or push-ups. If back squats are hard on your hips, try doing front squats. If the conventional deadlift is rough on your lower back, try doing split-stance Romanian deadlifts.

Nothing says that we need to use these variations forever. Perhaps as our muscles, bones, and tendons grow stronger, we can earn the ability to do harder lifts without pain. But in the shorter term, we want to train in a way that isn’t overly stressing our joints and connective tissues. Simply choosing lifts that suit us better is often the perfect solution.

What if We Feel Achy & Inflamed Overall?

Sometimes our lift selection is fine, and we still find ourselves feeling achy and inflamed. The reason this systemic soreness slowly sneaks up on you is that it gradually accumulates over time. Muscles usually recover within a couple of days, but it takes far longer for these other areas of your body to repair and grow.

So if you keep training hard week after week, it’s possible that your muscles are fully recovering, but you’re accumulating damage elsewhere. Some of these repairs are supposed to take place during deload weeks (which you should have every 4–10 weeks), but some will only recover when you ease back on your lifting in general, such as taking a couple of months every year where you stay within your comfort zone in the gym.

As a beginner, I would simply recommend that you follow a good lifting program. If you do that, you’ll never need to worry about managing these different recovery curves.

Should We Have a Sore Lower Back After Deadlifts?

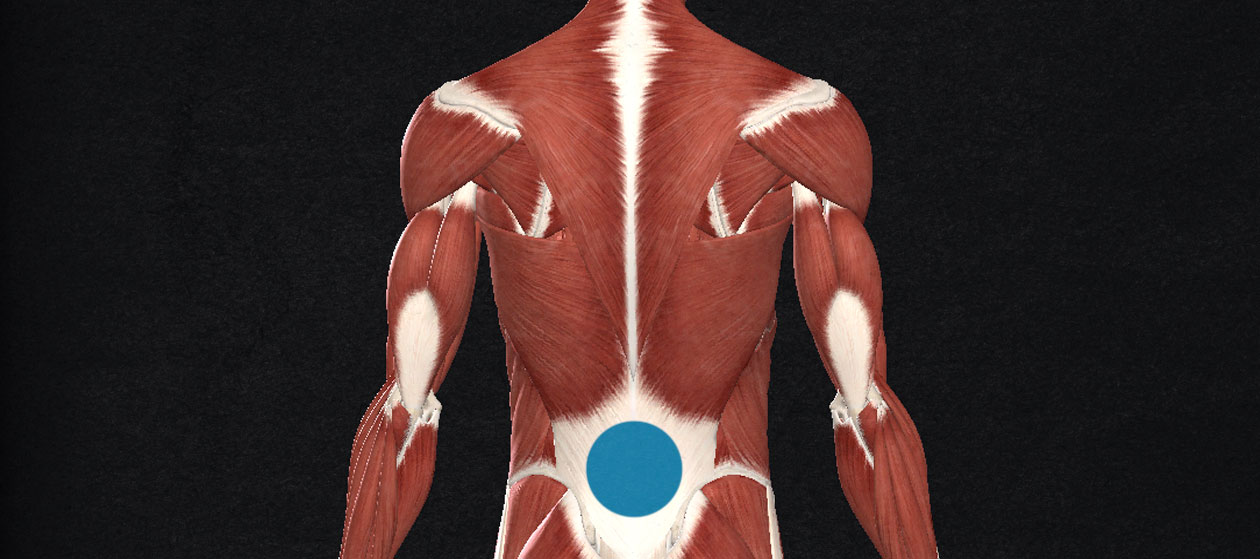

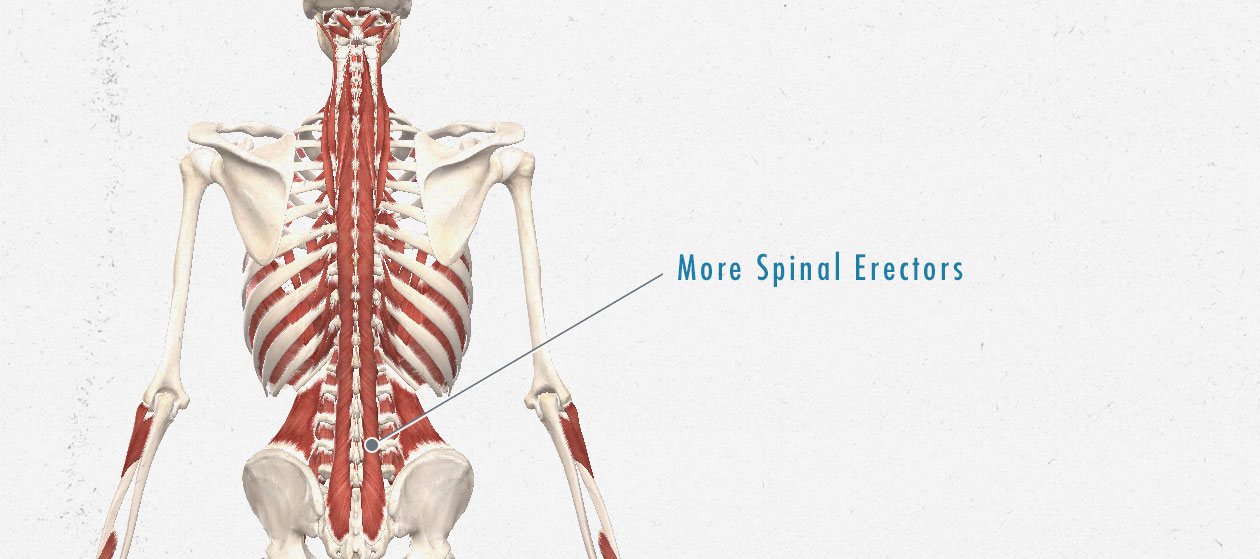

If you look at this image above, you can see why lower back soreness can be so scary. The red areas are the muscles, and the white areas are the tendons. As you can see, the lower back (blue circle) is covered with tendons, not muscles. So if that area becomes sore or inflamed, it’s not the beneficial muscle soreness; it’s the scarier tendon soreness… or is it?

To understand lower back soreness, we need to peel back the top a layer of musculature so that we can see what’s going on underneath, like so:

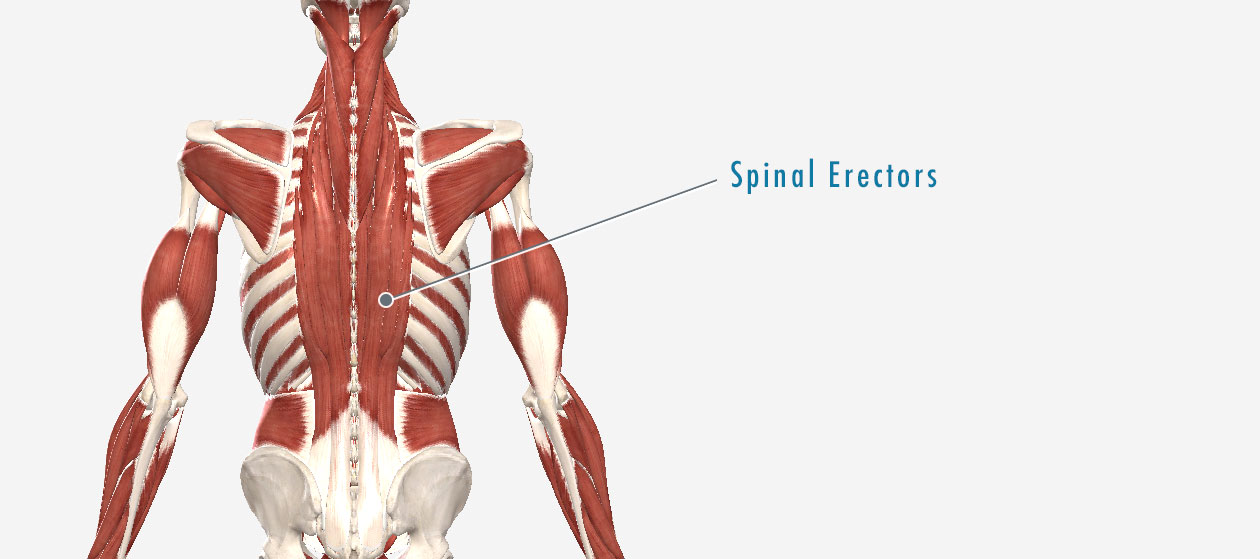

As you can see… the situation still looks kind of scary. The muscles go a little further down, sure, but it’s still just tendons covering your lower back. Worse still, those tendons might not feel all that sore, making it feel like the soreness is coming from even deeper—from around your spine itself. To figure out why that is, we need to peel back another layer:

Here we see a final layer of spinal erectors, buried deep under several layers of tendons, and butting up against your spine. As these muscles heal and grow, they’re going to go through a period of inflammation and soreness. This is why you’re so prone to feeling muscle soreness in your lower back after heavy lifting sessions, especially if you’ve been doing a lot of exercises that will help bulk up your back, such as front squats, conventional deadlifts, chin-ups, and rows.

Most soreness in your lower back muscles is good, but you do need to be mindful of your lower back when lifting. The lower back is a common area for injuries, and those injuries often take up to eighteen months to fully recover from. The healing process is painful, physiotherapy can be expensive, and it can really interfere with your bulking routine.

You’d probably still be able to lift weights with a lower back injury—and that’s often necessary in order to experience a full recovery—but you’d need to be more careful with your squats, deadlifts, and barbell rows. Far better to play it safe and avoid injuring your lower back in the first place.

The good news is that it’s quite rare to get a back injury while following a good hypertrophy program. Lower back injuries are more common in sedentary people going about their day-to-day lives as they haphazardly pick things up with weak back muscles and poor lifting technique. After all, the muscles that support their lower backs are weak, their connective tissues are fragile, and they never learned how to lift things properly.

Stressing your back in the gym is something to approach with care but not something to avoid. What you want to do in the gym is lift carefully and deliberately, making your back progressively stronger and tougher. Lifting weights should reduce your risk of a lower back injury by helping you avoid injury in your day-to-day life, both because you’ll have learned better lifting form and your lower back will be built up like a fortress.

How Can We Build Tougher Lower Backs?

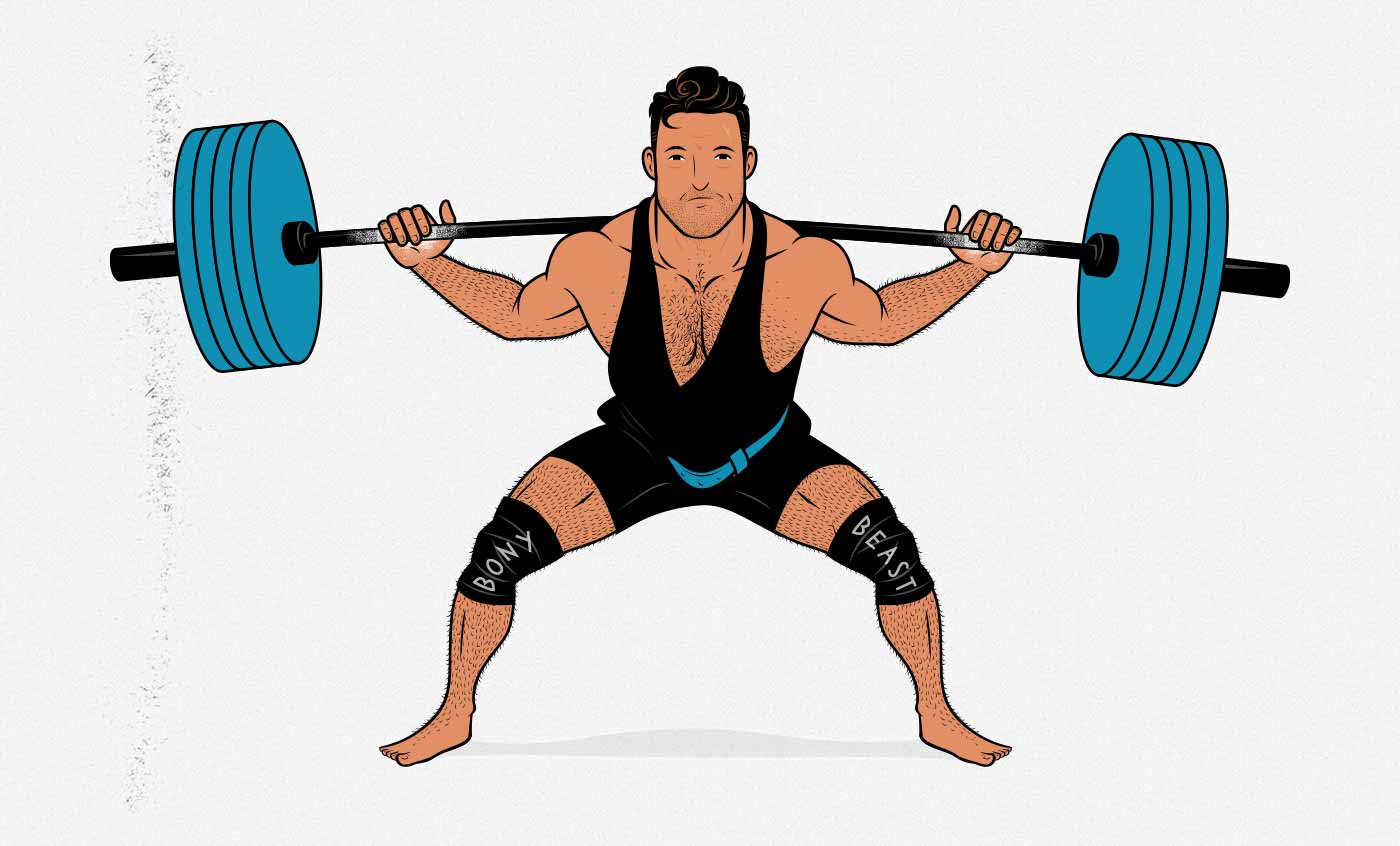

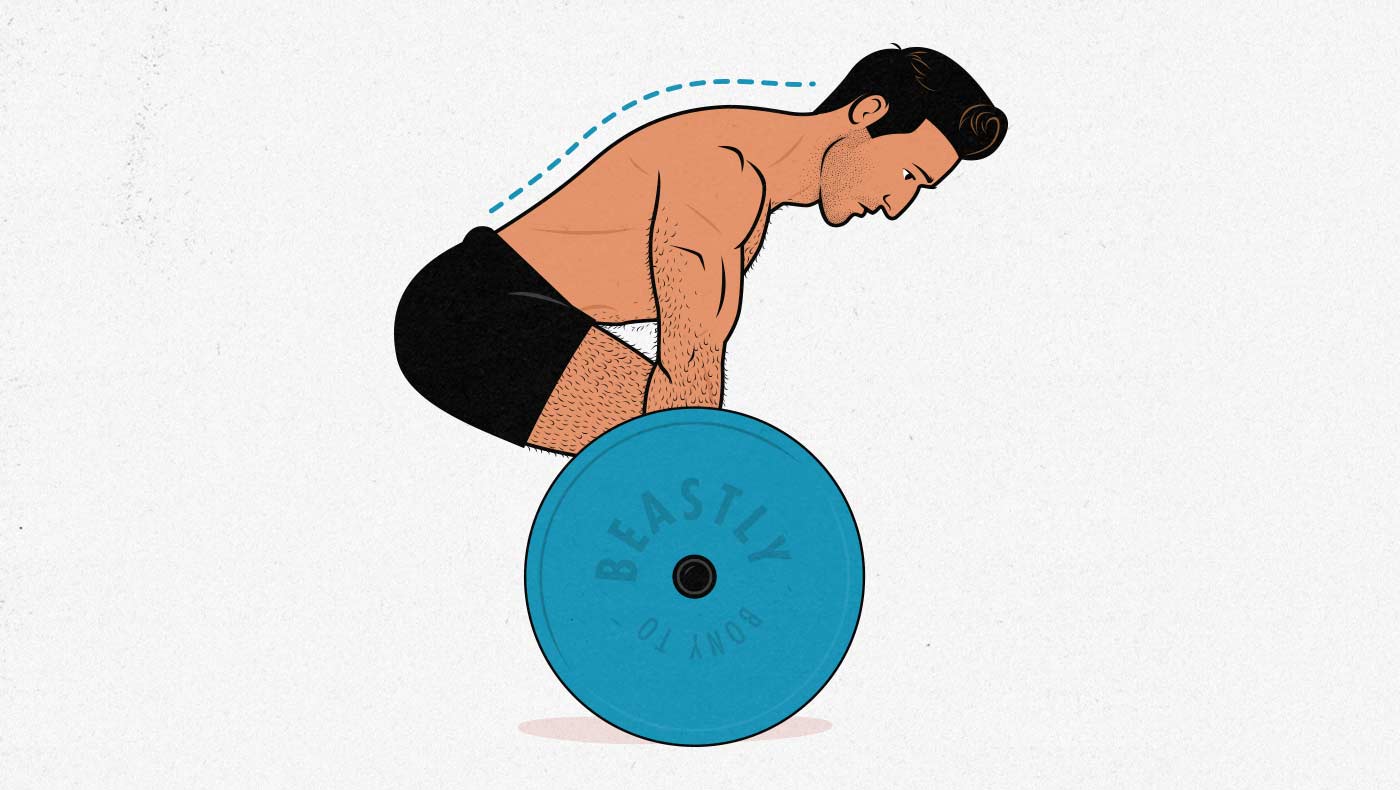

With most muscles, the best way to make them bigger and stronger is to lift a weight explosively through a large range of motion and then lower it under control. However, the safest way to train our spinal erectors is to train them isometrically—with no range of motion. If we contract them under load, yes, they’ll grow, but arching and rounding our spines can cause the connective tissues between our spinal discs to become softer and more flexible. That’s fine when doing things like yoga, but it’s not the adaptation we want for lifting weights.

To lift heavy things safely, we want the connective tissues between our discs to adapt by growing firmer, which is done by training our spines and spinal erectors isometrically. To do this, set your back in a neutral position and hold it there under load. When you squat and deadlift, use the muscles in your back to keep your spine from rounding or arching.

The cool thing about building up your spinal erectors is that they’re big muscles that run up your entire back. The bigger you make them, the thicker your torso will grow. Lats will make your back wider when seen from the back, but your spinal erectors will make your back thicker when seen from the side. If you’re like I was, and you look like a lollipop when you turn sideways, then it’s the squats, deadlifts, and bent-over rows that are going to really beef you up.

Anyway, after doing squats, deadlifts and bent-over rows, expect your lower back muscles to feel tired, and a couple of days later, expect them to feel sore. And that soreness will come along with inflammation, which can put pressure on your spine, which can feel… weird. But your spinal erectors have to go through that same healing and growth process as your other muscles, so it’s not something that we should avoid. In fact, of all the adaptations you make from lifting, I would argue that bulking up your back is the most important.

However, while rare, it is possible to injure your lower back while lifting. This often happens when people use so much weight that it causes their lower back to round or when they recklessly jerk the weight up off the ground. Keep in mind that your lifting technique doesn’t need to be perfect, though. “Neutral spine” is a range. A little bit of arching or rounding is generally considered safe, so if your back deviates a little bit while lifting, there’s no need to panic. Just keep practicing, and over time your coordination will improve.

If you’re feeling pain in your lower back while lifting, though, we want to be mindful of it. If you leave your hand on a hot stove for too long, you’ll get a burn. But if you yank your hand away as soon as you first feel pain, you can probably reduce the risk or severity of the injury. The same principle often applies when lifting weights. Pain in the gym often warns of a future injury, so if you experience pain in your lower back, that can be a sign to ease back on what you’re doing—to be more careful moving forward. (The same is true with other areas of your body. If you feel sharp pains in your shoulders while doing the bench press, stop. Fix the problem. Don’t just grind away at it. That’s how people injure their shoulders.)

How To Tell the Difference Between DOMS & A Back Injury

Soreness is a dull ache and tenderness that peaks 24–72 hours after lifting weights. If you feel soreness in your lower back muscles, that’s fine. Getting a “pump” or a “burn” in your back muscles is also fine. Your back muscles are muscles, so they’re going to burn and get sore.

It’s often the sharper “shooting” pains that warn of an impending injury. If you’re experiencing pain completely different from what you’ve been feeling in the other areas of your body, I’d recommend seeing a physiotherapist to get it checked out. On the other hand, if it feels more like muscle soreness, that’s probably a good thing. With proper rest and nutrition, the muscles that support your lower back should grow back stronger and tougher.

What If Your Lower Back Is Always Sore?

If your lower back muscles remain sore forever, not recovering as your other muscles do, that could be a sign that you’re not giving them adequate rest. This is usually a postural issue stemming from your hips being tilted too far forward, causing your lower back muscles to be perpetually flexing and tight. If your lower back muscles are always tight, they’ll never get a chance to rest and recover.

The good news is that a balanced lifting program should also help you improve your posture. After all, posture is almost always rooted in weakness. In this case, developing stronger abs and glutes that hold your hips in the proper position will do a great job of giving your lower back muscles some rest. This should resolve over time.

Another problem with a sore lower back is that you use your lower back for everything. During my first few weeks of over-zealous lifting, my spinal erectors were so sore and tired that I couldn’t even sit up straight in a chair. In our article on inflammation, we explained the problem with trying to reduce inflammation with anti-inflammatory drugs, ice, cold baths, and even antioxidant supplements, so what I’d recommend instead is to get some blood flowing in the area.

If your sore back is interfering with your day-to-day life or lifting, try doing some cat/camels (tutorial video) when you wake up in the morning and then again whenever you notice your lower back feeling especially sore or stiff. Once the blood starts flowing, the area should feel a bit fresher. You can do this before your workouts as well.

As you get used to the stresses of deadlifting, your lower back won’t just grow stronger, it will also grow tougher. It won’t get as sore or fatigued. You’ll be able to deadlift several hundred pounds and then go about your day like normal. That’s one of the best benefits of lifting weights: you’ll build a tough body capable of lifting heavy things without becoming overly stressed, fatigued or injured.

Summary

The soreness we get from lifting weights (DOMS) is a normal part of weight training. When we first start working out, it can be crippling and unpleasant. As we get bigger and stronger, we also grow tougher. As we grow tougher, our muscle soreness not only fades but also starts to feel more pleasant—almost like having gotten a massage.

The problem with being bigger, stronger, and tougher is that it can get harder to stress our muscles enough to provoke muscle growth. As a result, it’s important to focus on progressive overload: adding more weight, more reps, and more sets over time.

- More soreness isn’t always better. Soreness can be a sign that you’re challenging your muscles, which is good. If you’re following a good bulking program, that could be a sign that you’re stimulating muscle growth. However, more soreness isn’t always better. After all, the more muscle damage you cause, the more resources need to be invested in repairing that damage, leaving fewer resources available for building bigger muscles. Excessive damage will also extend the recovery process, interfering with your workouts and preventing you from stimulating a new wave of muscle growth. Some soreness is often good, but crippling soreness is usually bad.

- Beginners should be especially wary of causing excessive muscle damage. If you’re new to lifting weights, you should gradually ramp up your training over the course of a few weeks. This will reduce muscle damage, reduce soreness, and allow you to build more muscle. This doesn’t necessarily mean lifting lighter, but it probably means stopping each set a couple of reps shy of failure as well as keeping your workouts fairly short.

- When workouts stop making you sore, periodize your training. Muscles adapt to a bulking routine by growing bigger, stronger, and tougher. As your muscles become tougher, your workouts won’t cause as much muscle damage or soreness. This is why your workout routine should be ramping up in intensity from week to week to prevent your growth from plateauing. After a few weeks of ramping up the intensity, drop the intensity back down and begin the process again with different lifts and rep ranges.

- It’s okay to lift even if you’re still sore. A bulking workout will stimulate around 48 hours of growth, and muscle soreness peaks between 24–72 hours. If you want to keep your body steadily growing, you’ll need to be training while sore. The good news is that lifting while sore is safe; it’s great for building muscle and even reduces muscle soreness.

- If a muscle isn’t getting sore, make sure you’re stimulating it properly. If a specific muscle group isn’t experiencing any soreness, that might be a sign that your workout isn’t stimulating it, stressing it enough to provoke muscle growth. You might want to consider adjusting your technique or adding in some isolation exercises. For example, if doing the bench press doesn’t stimulate any soreness in your chest muscles, try benching with a wider grip or adding some pec flyes into your routine.

- It’s normal to have a sore, tired lower back after doing deadlifts, squats, and bent-over rows. Your back is supported by several different muscles, including your lats, glutes, and spinal erectors. These spinal erectors run up the entire length of your spine, and when they get sore, you’ll feel it in your lower back. These are beefy muscles with massive growth potential, and they’ll get sore after a challenging workout, so it’s totally normal to have a sore lower back after lifting weights. This isn’t a reason to panic. Remember that lifting weights will make you tougher, and having tough back muscles, bones, and tendons will help keep your back healthy.

Alright, that’s it for now. If you want to know the ins and outs of bulking up, we have a free newsletter. If you want a full muscle-building program, including a 5-month workout routine, a bulking diet guide, a gain-easy recipe book, and online coaching, check out our Bony to Beastly Bulking Program. Or, if you want a customizable intermediate bulking program, check out our Outlift Program.