Do Resistance Bands Build Muscle? Yes, But How Well?

Resistance bands are cheap, portable, and convenient. They challenge our muscles. What more do we need? There’s a whole grain of truth there. Resistance bands can stimulate muscle growth. Plenty of people get great results from training with them. You don’t need anything more.

But what if you’re trying to build muscle as quickly, efficiently, or painlessly as possible? Are resistance bands the best tool for that? That’s a different question. In that case, we need to compare resistance bands against the alternatives: bodyweight exercises, dumbbells, barbells, and exercise machines.

So, how do resistance bands compare to callisthenics and free weights? Let’s delve into it.

Introduction

Most beginners aren’t too thrilled about the idea of joining a gym. They’d much rather build muscle at home. Resistance bands are one of the most popular ways to do that. But why? Of all the ways to train at home, why resistance bands? Are they especially good for building muscle?

Some claim resistance bands are better for building muscle than free weights because of “variable resistance.” Elastic bands get progressively harder as your stretch them, creating a unique resistance curve. It’s what sets resistance bands apart from the cable machines you’d find at a gym. That raises a question. If variable resistance is good for building muscle, why do commercial gyms invest in equipment that provides the opposite resistance curve?

And why are free weights so popular? They’re bulkier and more expensive than resistance bands. If they’re worse for building muscle, why bother with them at all?

You Can Build Muscle With Anything

Before we dive into whether resistance bands are ideal for building muscle, it’s worth pointing out that we can build muscle in imperfect situations. You don’t need to build muscle in the “ideal” or “optimal” way.

If you can do these three things, you can build muscle:

- Eat enough calories to gain weight: the ideal rate of weight gain depends on how skinny you are, how new to lifting you are, how lean you are, and how aggressively you want to bulk. But the important thing is that you gain at least some weight on the scale each week.

- Eat enough protein to build muscle: about one gram of protein per pound bodyweight per day is a good rule of thumb. Fat and carbs are important and nutritious, too, but you probably already eat enough of them.

- Challenge your muscles. This signals your body to invest in muscle growth.

If you can do those three things, you can build muscle. You could build muscle stranded on a desert island with nothing but your body weight and a weight-gainer supplement. I’m also confident that you could clean your house with a toothbrush and some vinegar. There’s a difference between something being possible and something being easy.

Not everything needs to be optimal. I know people who have decently muscular physiques from swimming laps in a pool. Some people gain an abundance of muscle as a byproduct of becoming overweight. Other people have already built muscle and are just trying to maintain their size, strength, and health in an enjoyable way.

But I’m coming at this from the perspective of the skinny guy who was desperate to bulk up. When deciding what equipment to buy, I didn’t want to see a photo of a muscular fitness model holding resistance bands saying, “Anything is possible with hard work, sweat, and a credit card!” No, I wanted to know what the pros and cons were. I wanted to know how resistance bands compared to barbells, dumbbells, and kettlebells.

Are Resistance Bands Good for Building Muscle?

Whether we’re using resistance bands or free weights, the same general principles of muscle growth still apply. We need adequate rest between sets so that we’re limited by the strength of our muscles rather than by our cardiovascular fitness. If our workout is a long circuit designed to leave us winded, that’s not hypertrophy training, that’s cardio. That disqualifies a lot of bodyweight workouts, resistance-band workouts, and even free-weight workouts, but it doesn’t mean the tools are inappropriate, just the training style.

Whether we’re using free weights or resistance bands, we still want to focus on the big compound lifts, add in some isolation lifts, lift with a large range of motion, bring our sets close to muscular failure, and do enough of those challenging sets each week. So let’s review these principles and how they apply to resistance bands.

The Problem of Variable Resistance

As a rough rule of thumb, lifting with a deep range of motion is good for building muscle. It forces our muscles to do more work, we stimulate a wider variety of muscle fibres, and we often engage more overall muscle mass. But there’s some nuance to it, too. Two specific parts of the range of motion are disproportionately important:

- The sticking point: our muscles only grow when we challenge them, and some parts of the range of motion are more challenging than others. The sticking point is the most challenging part of the range of motion. That’s where we tend to fail, and it’s also where we tend to stimulate the most muscle growth. For example, the sticking point of a squat is when our thighs are horizontal with the ground. If we squat to that point, we get most of the benefit of squatting, so it’s considered a “complete” squat. If we squat higher than that, it’s considered a “partial squat,” and we miss out on some muscle growth.

- The stretch at the bottom: the most important benefit of increasing our range of motion beyond the sticking point is that it allows us to get a loaded stretch on our muscles at the bottom of the lift. For example, if we squat even deeper, we’ll get an even better stretch on our quads, and we’ll stimulate even more muscle growth. This is probably why deep front squats and goblet squats stimulate just as much muscle growth as back squats, even though back squats are much heavier. This is also why seated hamstring curls, which put our hamstrings under a deeper stretch, build muscle faster than lying hamstring curls (study).

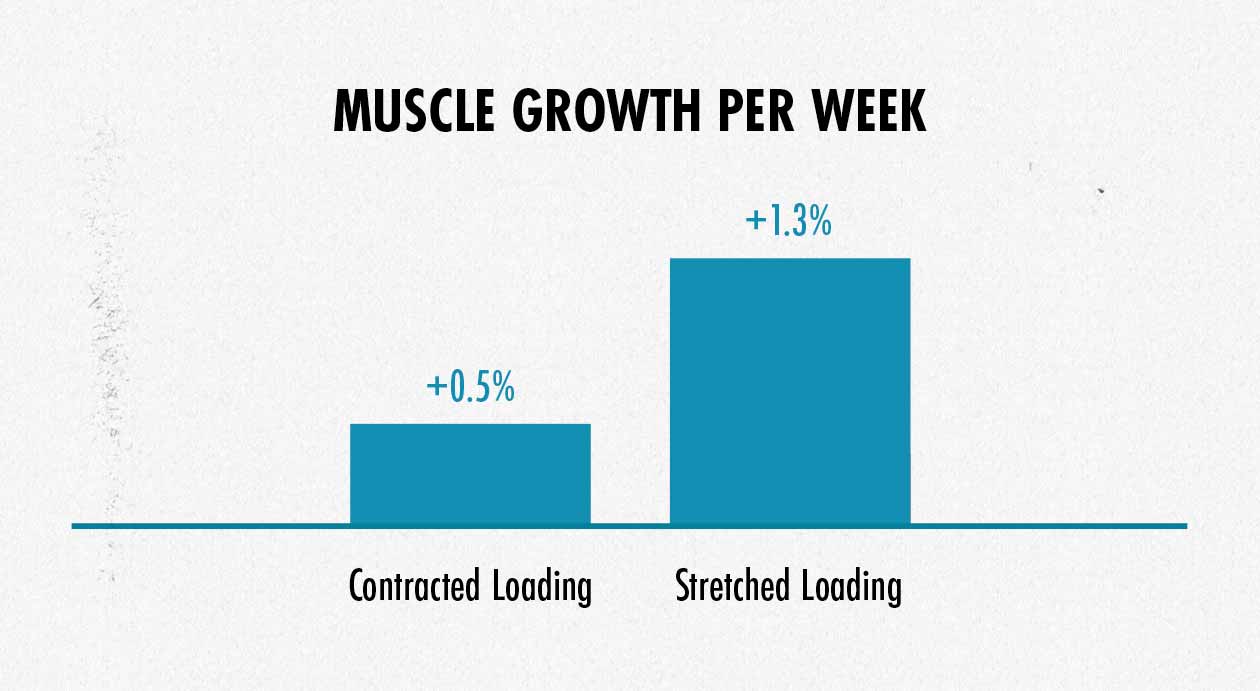

But how much does it matter? Are we talking about a 5% difference in muscle growth? 30%? 50%? This is where things get interesting. Let’s look at a meta-analysis of the relevant studies. Challenging our muscles in a stretched position stimulates 260% as much muscle growth as challenging them in a contracted position:

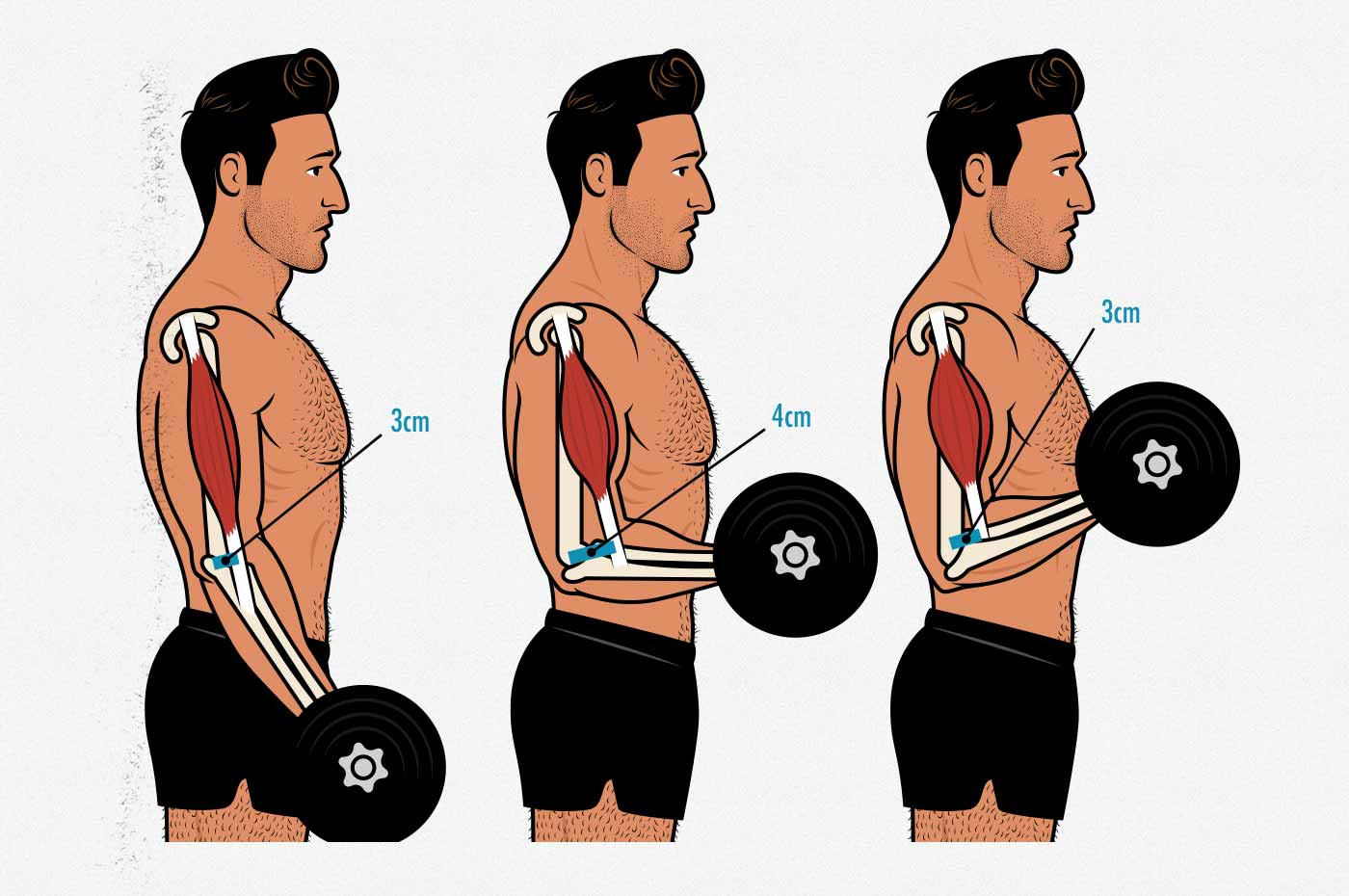

These findings have been confirmed by several recent muscle-building studies, too (Pedrosa, Maeo, Yanagisawa), with more coming out every month. All of them show that challenging our muscles at longer muscle lengths leads to greater muscle activation and 2–3x more muscle growth. This explains why deep squats, bench presses, Romanian deadlifts, and push-ups stimulate such tremendous amounts of muscle growth. They all challenge our muscles in a stretched position.

The next question is, why does challenging our muscles in a stretched position stimulate so much muscle growth? The main way we produce force with our muscles is by contracting them (active tension). But our muscles are like resistance bands. When we stretch them, they pull themselves back toward their resting length, creating passive tension.

When we contract our muscles as hard as possible while stretching them, we combine both active and passive tension. This puts more overall tension on our muscles. Tension is the main driver of muscle growth, so having more of it means more muscle growth.

Now, you might be thinking, what does this have to do with resistance bands? After all, nothing is stopping us from using a full range of motion with resistance bands, right? And if we use resistance bands properly, we can ensure tension on our muscles at the bottom of the range of motion.

The problem is resistance bands gradually apply more force the further we stretch them, making the bottom of the range of motion much easier than the top. We aren’t giving our muscles enough of a challenge at the bottom of the movement, so we aren’t getting the full benefit of training at longer muscle lengths.

Free Weight Strength Curves

“Variable resistance” is the term used to describe the resistance curve of resistance bands. To understand how that affects muscle growth, we can compare that resistance curve against the natural strength curves of our muscles to see how well they match up. If resistance bands are tough where we’re strong and loose where we’re weak, that’s a good match. But if they’re tough where we’re weak and loose where we’re strong, that’s a poor match.

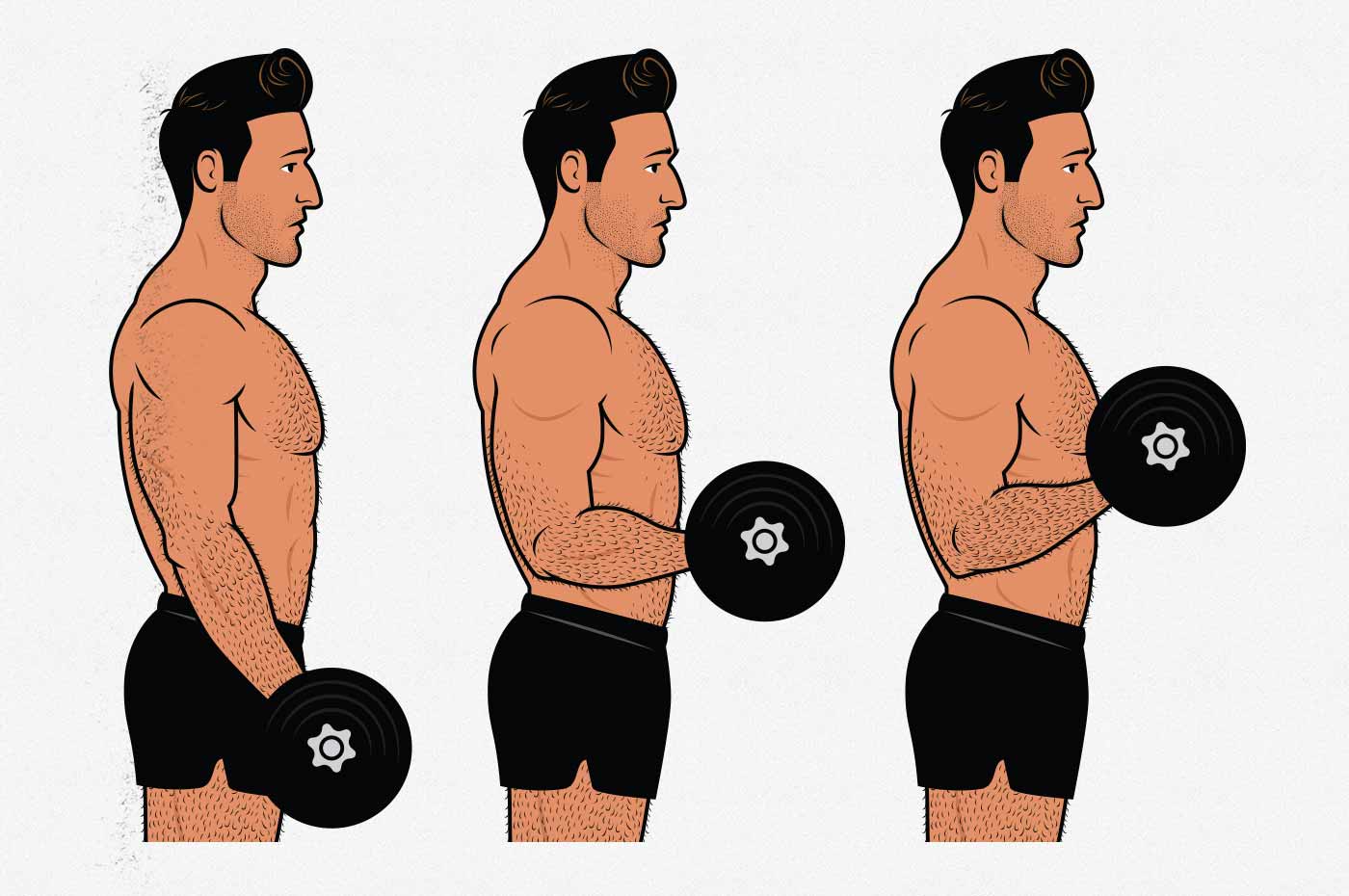

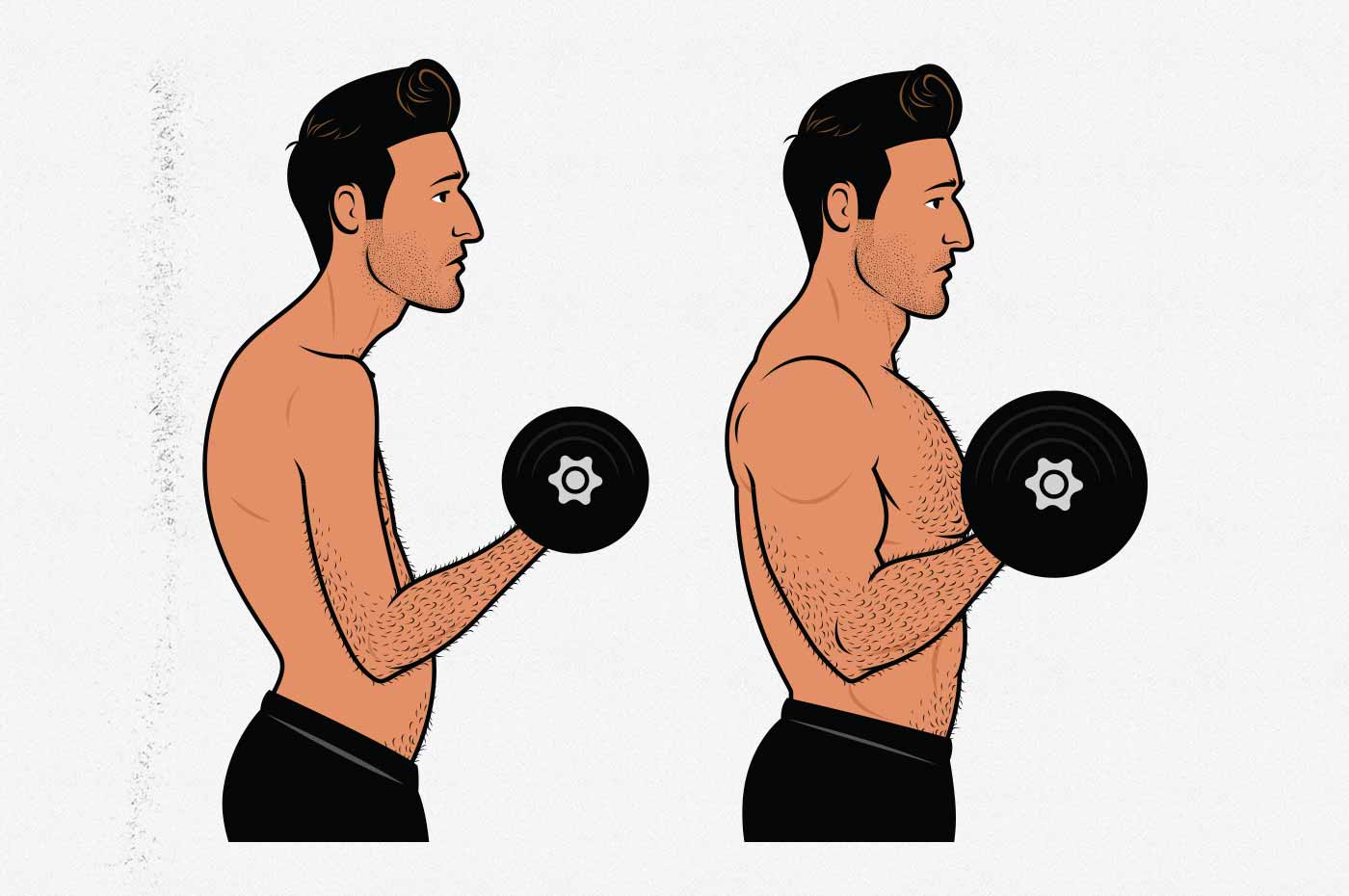

If we look at the dumbbell curl, we see that we can work our biceps through a fairly complete range of motion. We don’t get a full stretch at the bottom, but our biceps are at least brought to their full resting length (or slightly beyond). But as discussed above, we also need to see if our muscles are being challenged throughout that range of motion.

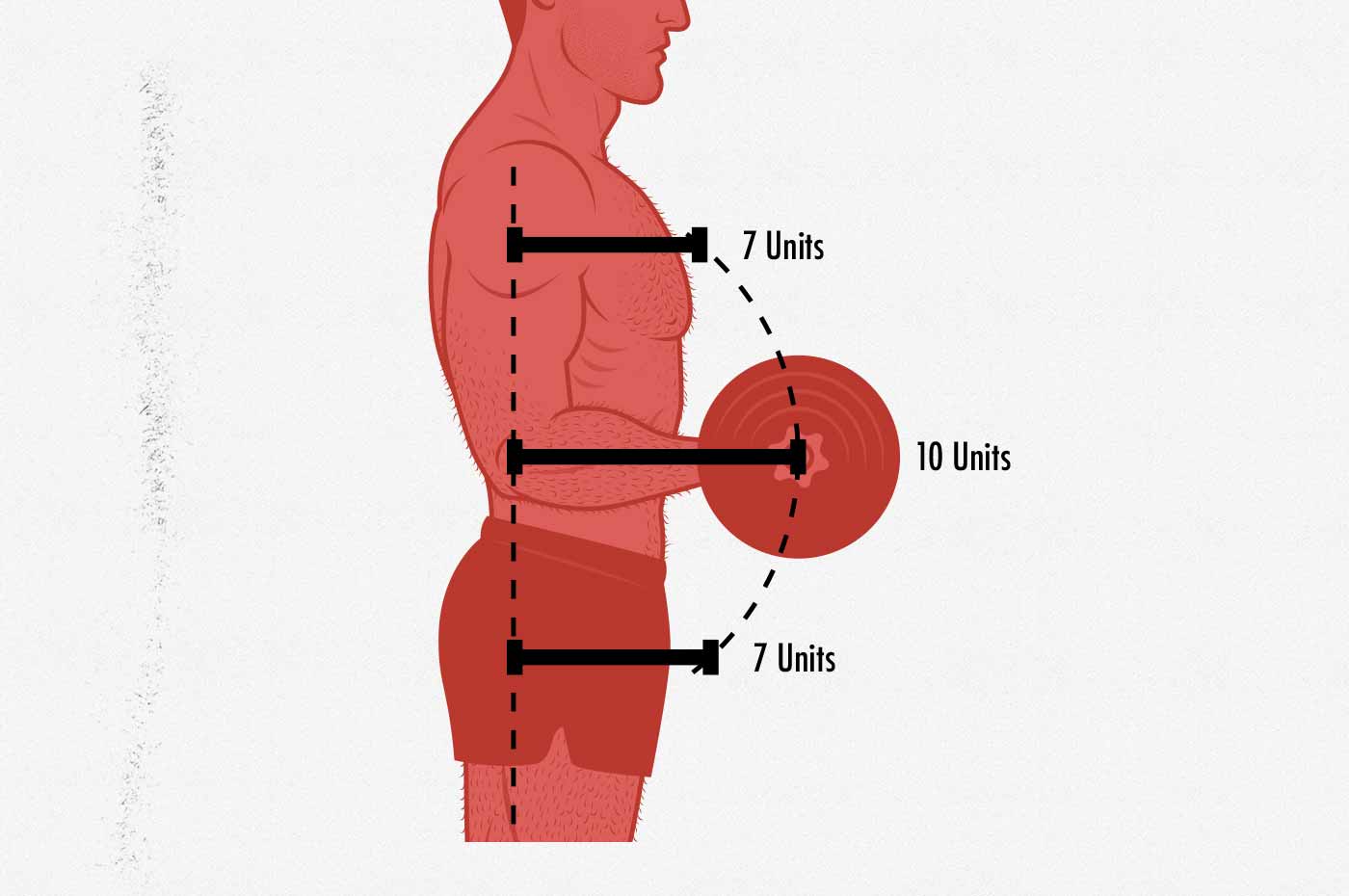

The beginning of the lift is fairly easy, it gets harder in the middle (when our forearms are horizontal), and then the lift gets easier again. In that middle position, the weight is about 40% heavier, so most people will fail there. That’s the sticking point. However, we also need to factor in our internal leverage:

Those little blue lines represent the moment arms created by our muscle insertions and joint angles. That shows that our biceps have poor leverage at the start, we get stronger in the middle, and then our leverage gets worse again at the top.

I’m using loose numbers here, but in this example, our leverage is about 30% better at the sticking point. Most (but not all) of the resistance curve is cancelled out by our internal leverage. The dumbbell is light at the beginning and end of the lift because that’s where we’re weaker. The dumbbell is heaviest in the middle because that’s where we’re strongest.

Most free weight lifts are like bicep curls, with their resistance curves at least partially flattened by our natural strength curves. We’re strongest at the toughest part of the squat, the bench press, and the deadlift, too. This allows us to lift fairly heavy weights, and it means our muscles are challenged through most of the range of motion (including at the bottom, which is key).

Our bodies are built to lift free weights. Of course they are. We’ve been lifting things against gravity for millions of years.

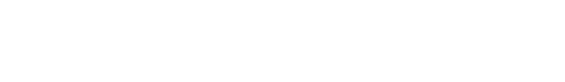

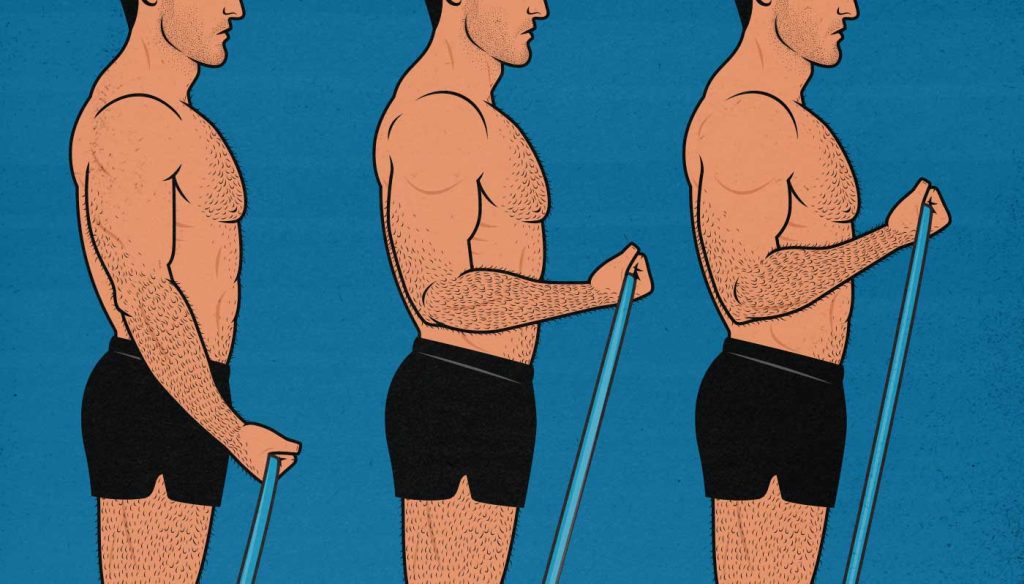

Resistance Band Strength Curves

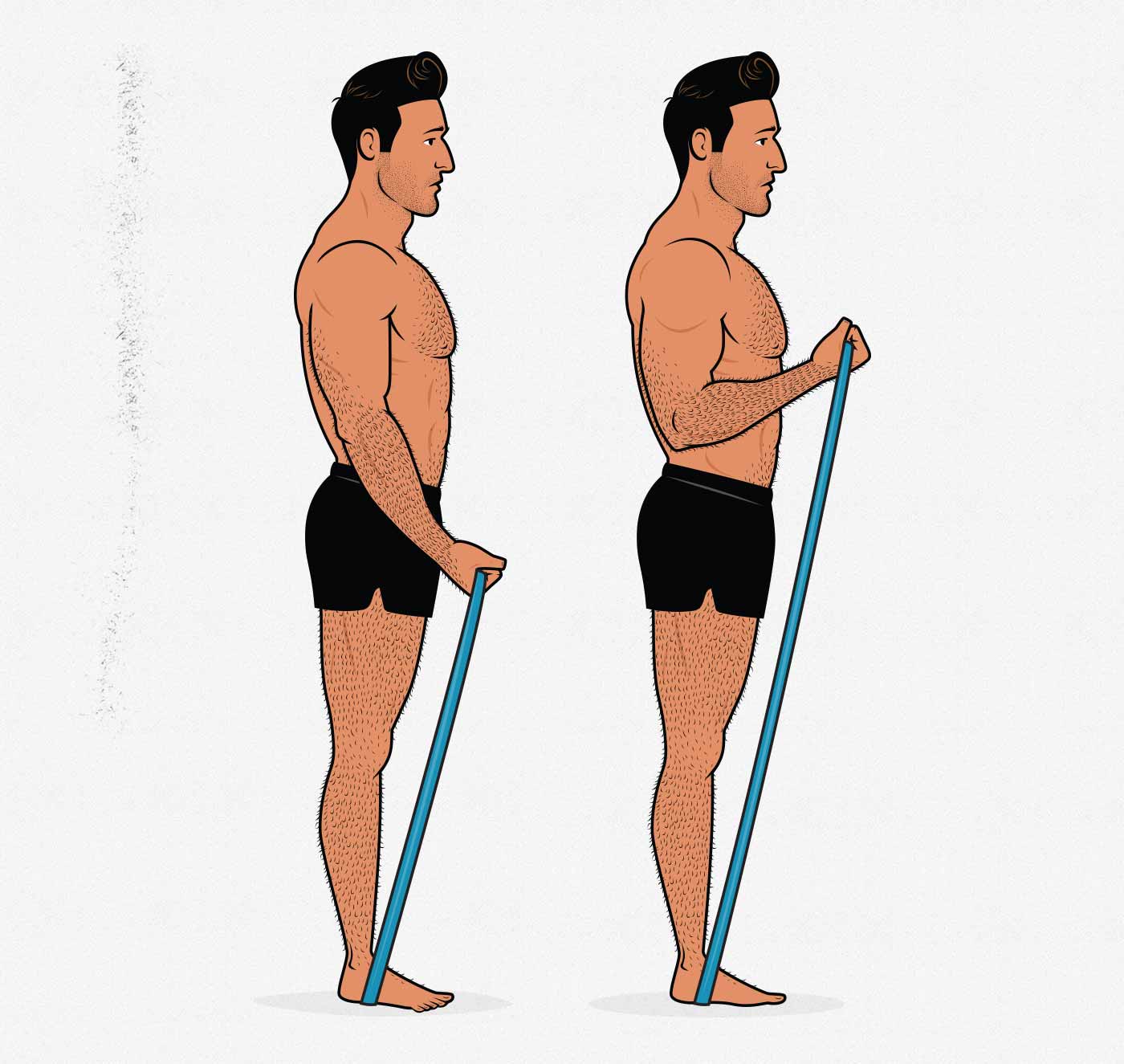

Okay, so what happens when we look at resistance bands? In this case, assuming we hook the bands under our feet, the line of pull is great. That slightly backward angle means that we can actually get a bit more of a stretch on our biceps in the bottom position and that the sticking point will shift a little bit lower. That’s good.

So at first glance, resistance-band curls appear to be better than dumbbell curls. But resistance bands are not the same as cables. Resistance bands have variable resistance. As we stretch resistance bands further, the load gets progressively heavier. The beginning is fairly easy. The band only truly challenges our muscles at the end. We’ve turned a full biceps curl into a partial biceps curl. And, worse, it’s the most important part of the range of motion that’s rendered most useless.

Now, there are a thousand caveats here. We could pre-load the resistance band with enough tension to fail at the beginning of the range of motion. We could attach the resistance band at different angles. We could even do several sets with varying degrees of tension so that we fail at varying parts of the range of motion. Or we could take the set long past failure, to the point where we can’t stretch the band a single inch. But none of that is ideal. Resistance bands still make it harder to build muscle.

But just to make sure, I also asked the hypertrophy researcher, Eric Helms, Ph.D. He said, “Not a lot of research on the topic, but I would agree with your general recommendations of free weights and machines for hypertrophy, with bands and bodyweight working in a pinch.”

Accommodating Resistance

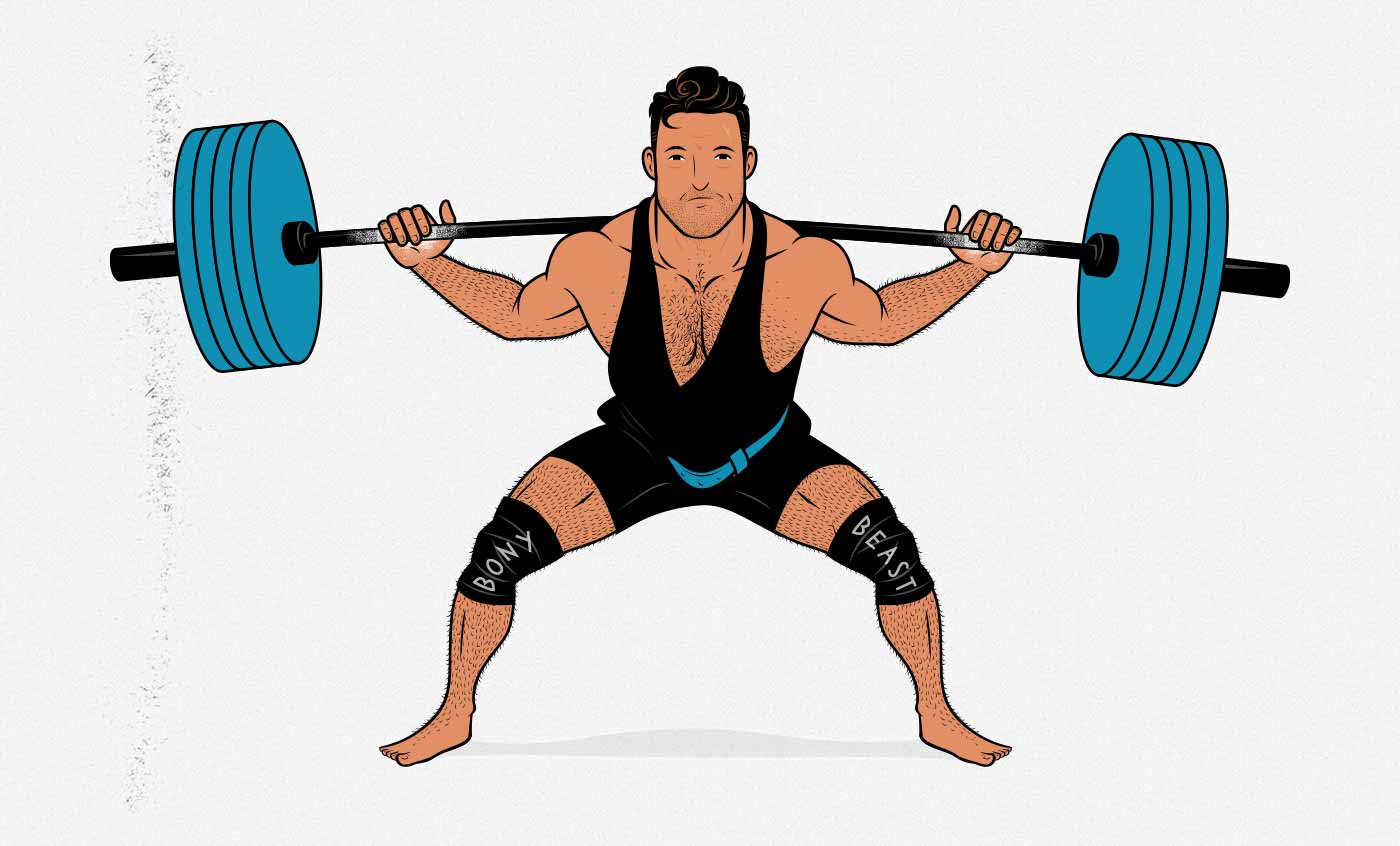

Accommodating resistance is when we add resistance bands or chains to free-weight lifts, such as the barbell back squat, bench press, and deadlift. Sometimes it’s used as an example of how resistance bands can be good for gaining muscle size and strength, but it’s actually quite different. To understand why that is, we need to understand what it’s for and what it does.

Accommodating resistance originated in geared powerlifting, where lifters would compete in squat suits, bench press shirts, and knee wraps designed to give them extra strength at the bottom of their lifts.

For example, let’s consider adding resistance bands to a barbell squat. Powerlifters do everything they can to improve their squatting leverage: standing with a wider stance, sitting further back, and holding the barbell lower on their backs. This creates a squat with a shortened range of motion, and it makes the bottom of the lift very hard. The bottom being hard isn’t a problem for building muscle, but to win at their sport, they need to lift the most weight possible.

One way to make the bottom of a squat easier is to wear a squat suit that stretches out at the bottom, giving the hips a boost. Another trick is using knee wraps, which stretch out at the bottom, helping them spring back up. This helps to flatten the strength curve. The beginning of the lift is still the sticking point, but it’s a bit easier, so they’re able to lift a bit more weight.

But powerlifters wanted to lift a lot more weight, and as squat suits and knee wraps got thicker, the strength curve began to reverse. The beginning started to become the easier part of the lift, and the lockout started to get harder. That changes the type of strength a powerlifter needs.

Now, how can a geared powerlifter train their lockout strength? One option is to train in squat suits, bench shirts, and knee wraps. But those clothes are a pain to put on, and the training is rough to recover from. Fortunately, their weird strength curve can be mimicked by attaching bands (or chains) to a barbell. If the bands make the lift heaviest at the top, the powerlifter can focus on training their lockout strength.

Nowadays, raw powerlifting is more popular than geared powerlifting. It’s rare to see a powerlifter who wears knee wraps and a triple-ply squat suit. Unless someone plans on wearing gear, that style of accommodating resistance isn’t needed.

But then, a new idea started cropping up. Couldn’t we build more muscle if we made the entire range of motion equally challenging? That doesn’t seem to be the case. Recent research has shown that the deepest part of the range of motion is by far the most important. Making the other parts more challenging doesn’t seem to help.

Resistance Bands Without the Barbell

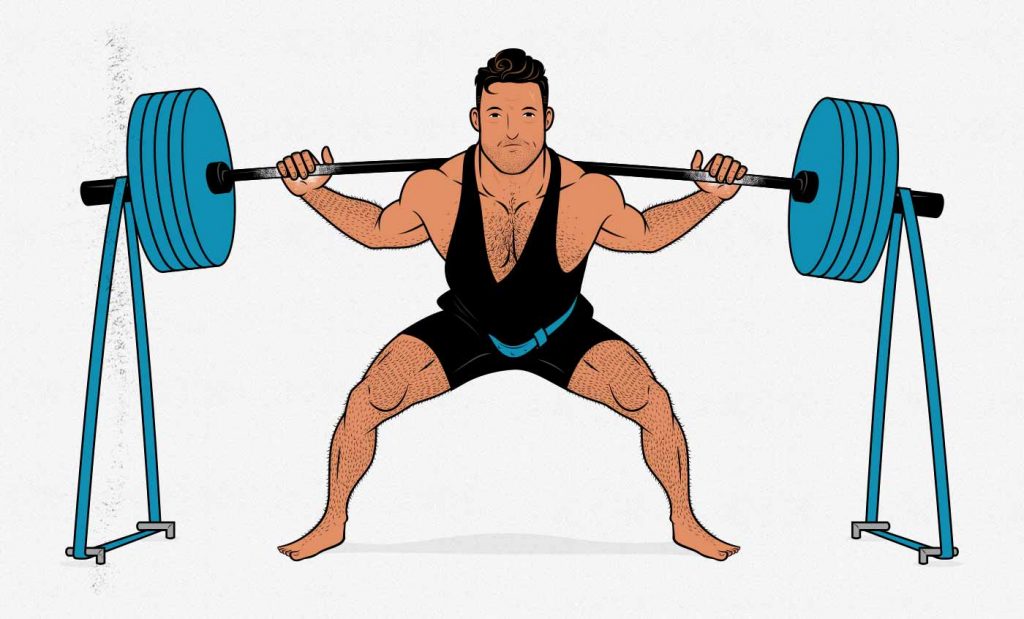

What if we remove the free weights entirely and squat with ONLY resistance bands? In that case, we’re making the resistance curve radically worse for stimulating muscle growth. Not that the lift becomes useless; it’s just that doing a regular squat with free weights would be much better.

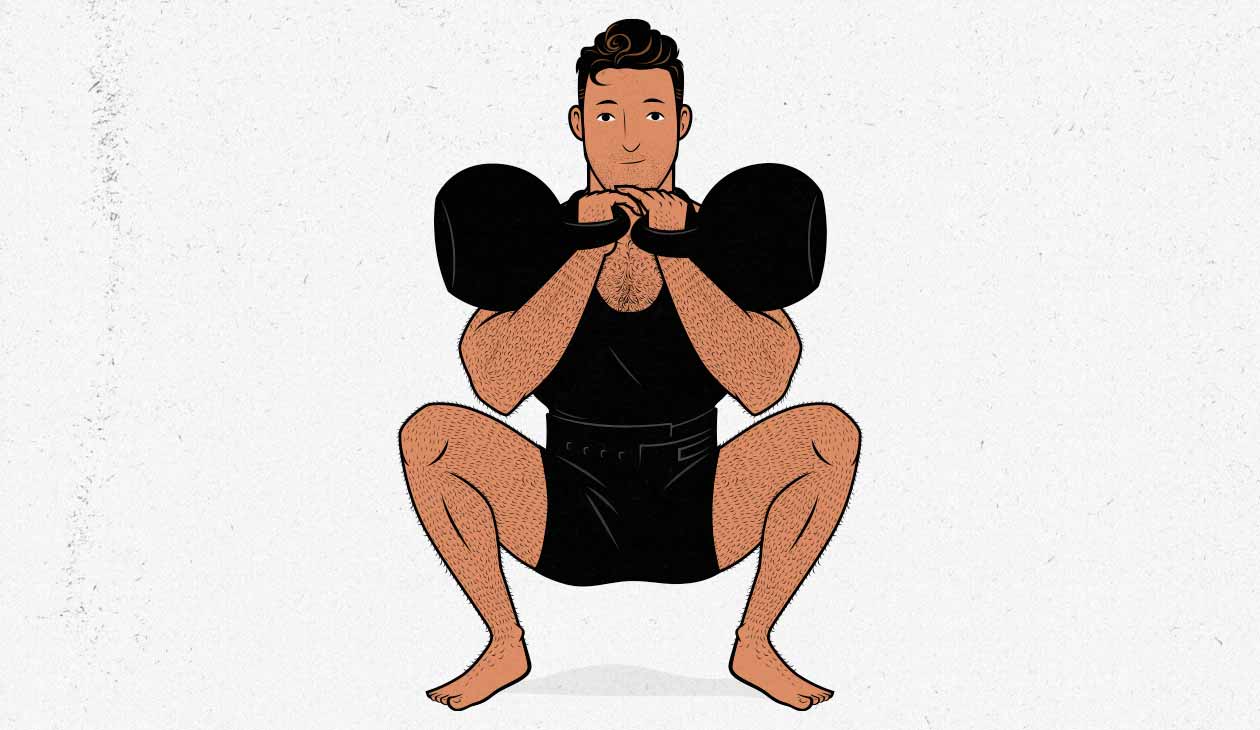

Moreover, if we’re training to gain muscle size and general strength, shouldn’t be lifting like powerlifters. Instead of doing our squats with a wide stance and a shortened range of motion, probably better to do a deeper squat with the weight held in front of us. It reduces the amount of weight we can lift, yes, but it works our muscles through a longer range of motion, and it does a better job of bulking up our upper backs.

The sticking point of a squat is always when the thighs are horizontal. The front squat goes much deeper than that. This changes the strength curve. If we explode out of the hole, we can gather some momentum to help us drive through the sticking point. Plus, the tension on our upper backs comes from holding the weight in front of us, which is constant throughout the entire range of motion. The lockout is still the easiest part, so accommodating resistance might still help, but the strength curve is already a bit flatter.

This same general trend is true of the other big compound hypertrophy lifts. Powerlifters bench press with big arches, reducing the stretch on our chests at the bottom of the lift. That’s bad for building muscle, so when lifting for hypertrophy, we use a smaller arch and focus on getting a bigger stretch. This gives us a bench press with a flatter strength curve and thus diminishes the value of accommodating resistance. Not that it’s necessarily useless, mind you, just not all that important.

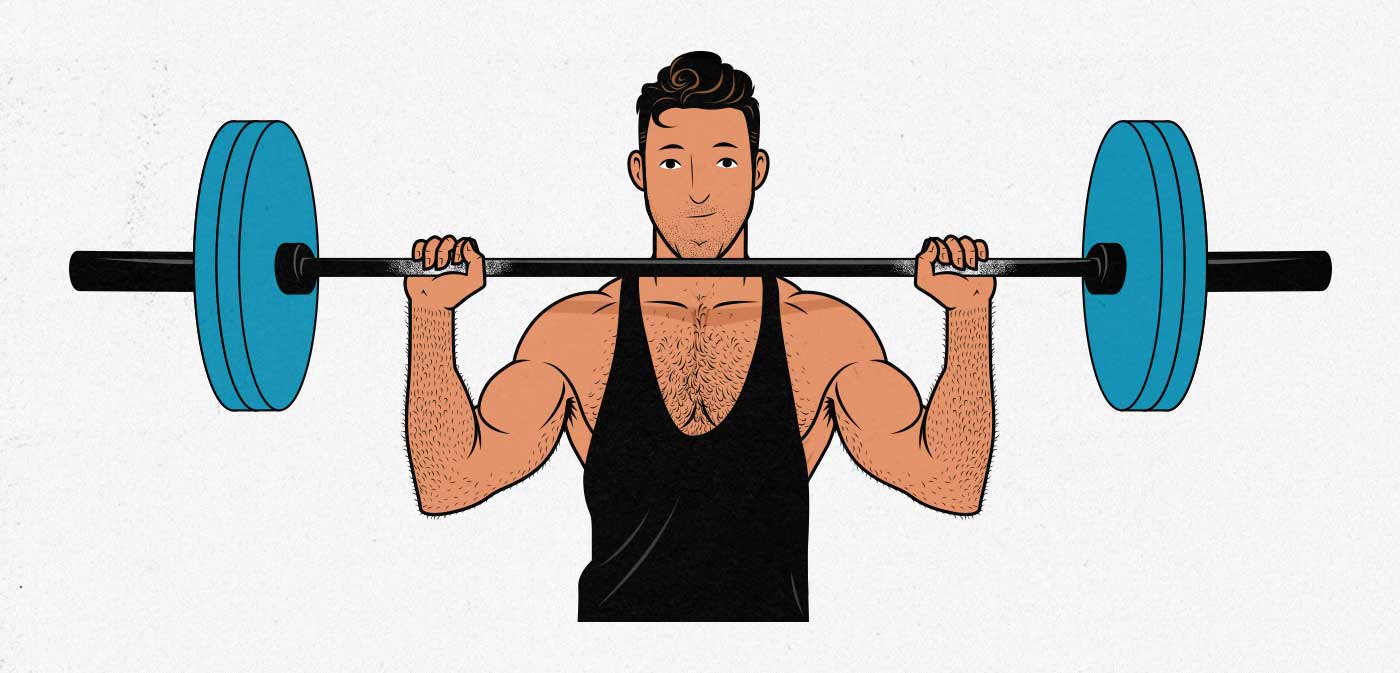

The Big Compound Lifts

Most of our muscle growth comes from doing the big compound lifts. Let’s review some examples of how using resistance bands change the dynamics of the big compound lifts.

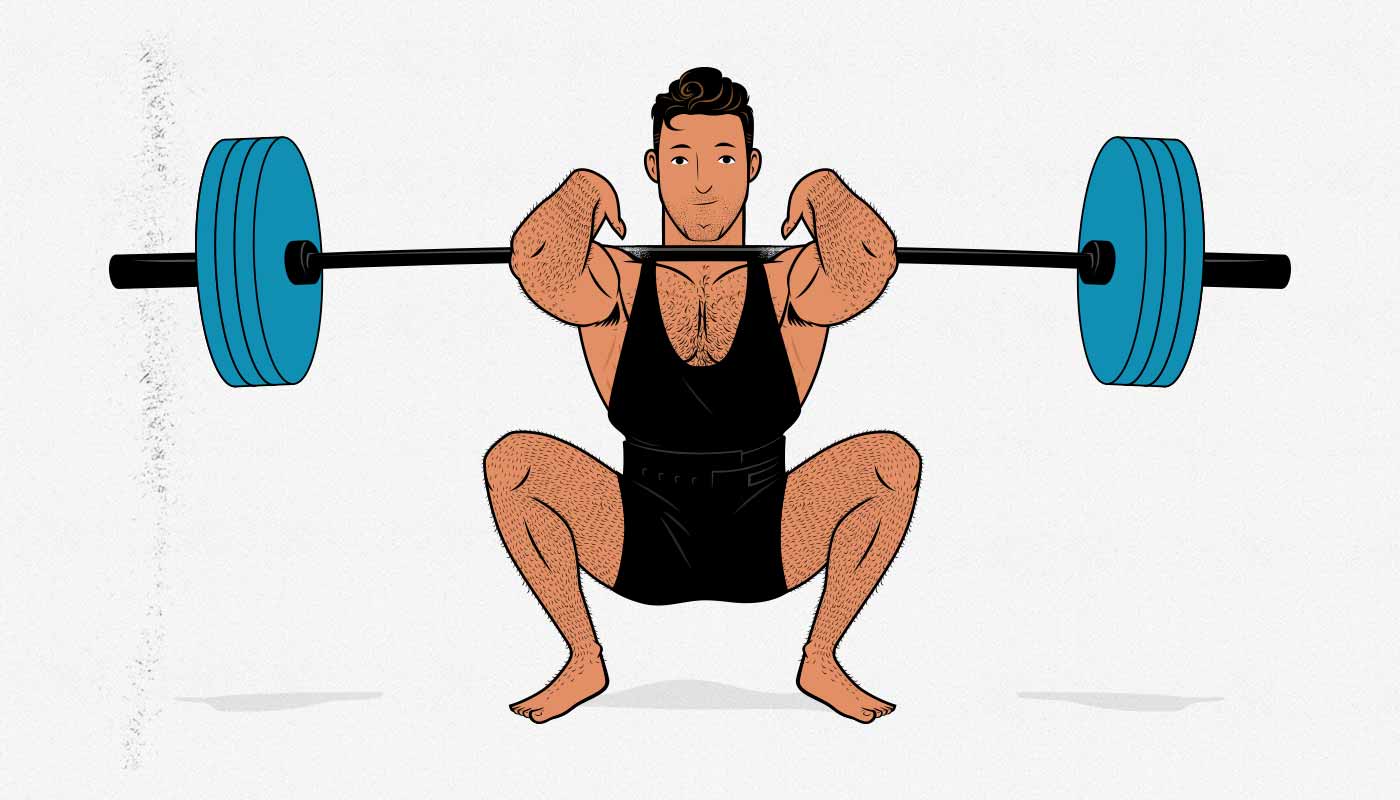

Consider a front-loaded squat done with a barbell, dumbbells, or kettlebells, where we squat down as deep as our hips and knees allow, getting a nice stretch on our quads. These have proven, time and time again, to be better for building our quads than partial squats, even though partial squats are twice as heavy. Why is that? It’s because with a partial squat, we’re cutting out the most important parts of the range of motion: the sticking point and the stretch.

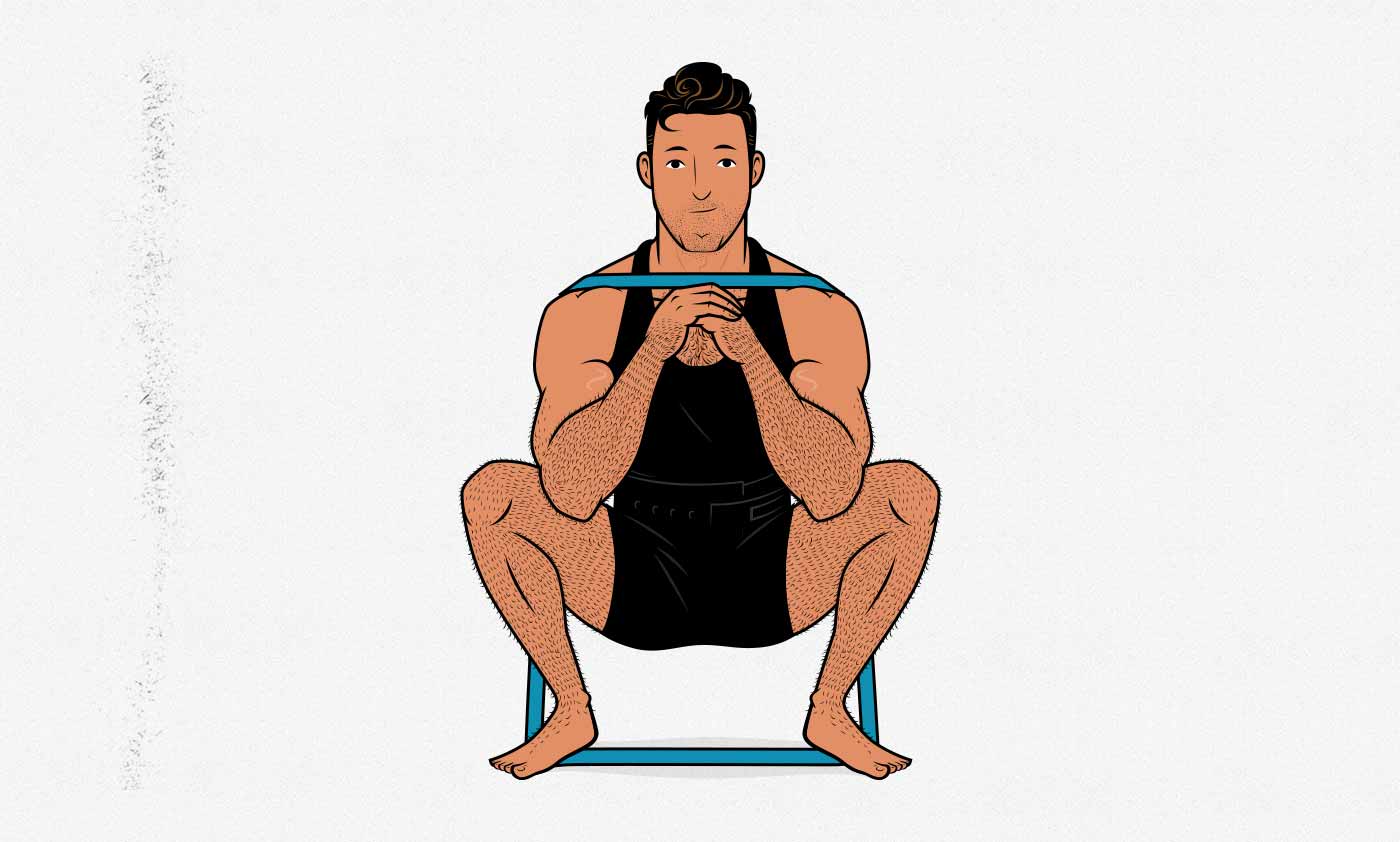

Now consider what happens when we do bodyweight squats with resistance bands. In the bottom position, the resistance band is loose, so it’s very easy. Not good. As we get closer to the top of the range of motion, the resistance band is stretched, so the lift gets harder. This means we’re only truly challenging our quads at the top of the range of motion. That’s not great for building muscle. Better than nothing, for sure, but it might not be better than body weight. We may build more muscle by doing bodyweight single-leg squats, where the bottom is the heaviest part of the lift:

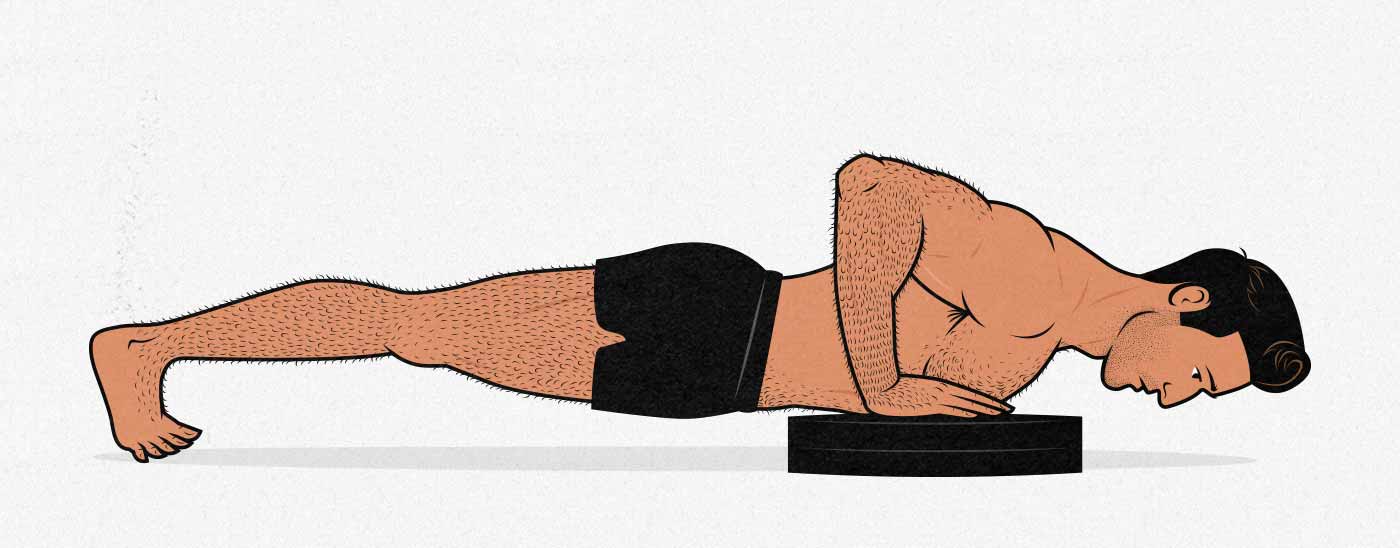

The same is true with push-ups. Yes, we can load it heavier with resistance bands, but they make the top of the lift disproportionately harder. This means we’re no longer challenging our chests in a stretched position. Rather, we’re challenging our triceps at the lockout. A better way to replace the bench press is with the deficit push-up, where we raise our hands up so that we get an even bigger stretch on our chests and make the bottom of the lift harder:

We start to run into problems when we get to back training. Most back lifts already have fairly poor strength curves. They’re easy at the bottom, hard at the top. That’s why it’s so hard to touch the barbell to our chest when rowing, and so hard to touch our chests to the bar when doing chin-ups. If we add resistance bands to these pulling movements, they become atrocious. Resistance-band rows are incredibly easy at the start and extremely difficult at the end. Getting a cheap chin-up bar that you can bolt onto a wall or hook onto a doorframe doesn’t completely solve the strength curve, but it’s much better.

Different Lines of Pull

One feature of resistance bands is that depending on where we anchor them, we can create different lines of pull. That’s the same advantage of using a cable machine, and it can definitely be handy. However, that’s usually accompanied by the statement that because free weights resist gravity, they only allow us to train with a single line of pull. That’s not true, and it’s easy to see why.

If we think of a dumbbell or barbell overhead press, it’s true that, yes, we’re just pressing the weight straight up. It’s a vertical press. So the advantage that bands offer is that we can anchor them to a wall or door frame and create a horizontal press, right? That’s true.

But we can change the line of pull by changing the angle of our torsos. That gives us a bench press, a floor press, or a push-up. These free-weight variations have better strength curves for gaining muscle size and strength.

If we think about back movements, it’s the same thing. Chin-ups are a vertical pull, yes, but that does not limit us. If we bend at the waist, we can do horizontal rows with a barbell or dumbbell. And again, the free-weight variation has a strength curve that’s better for building muscle.

This isn’t to say that resistance bands don’t offer any advantages. Being able to anchor the resistance bands in different positions can indeed allow us to get creative with our lifts. I think that’s one of the cooler things about them.

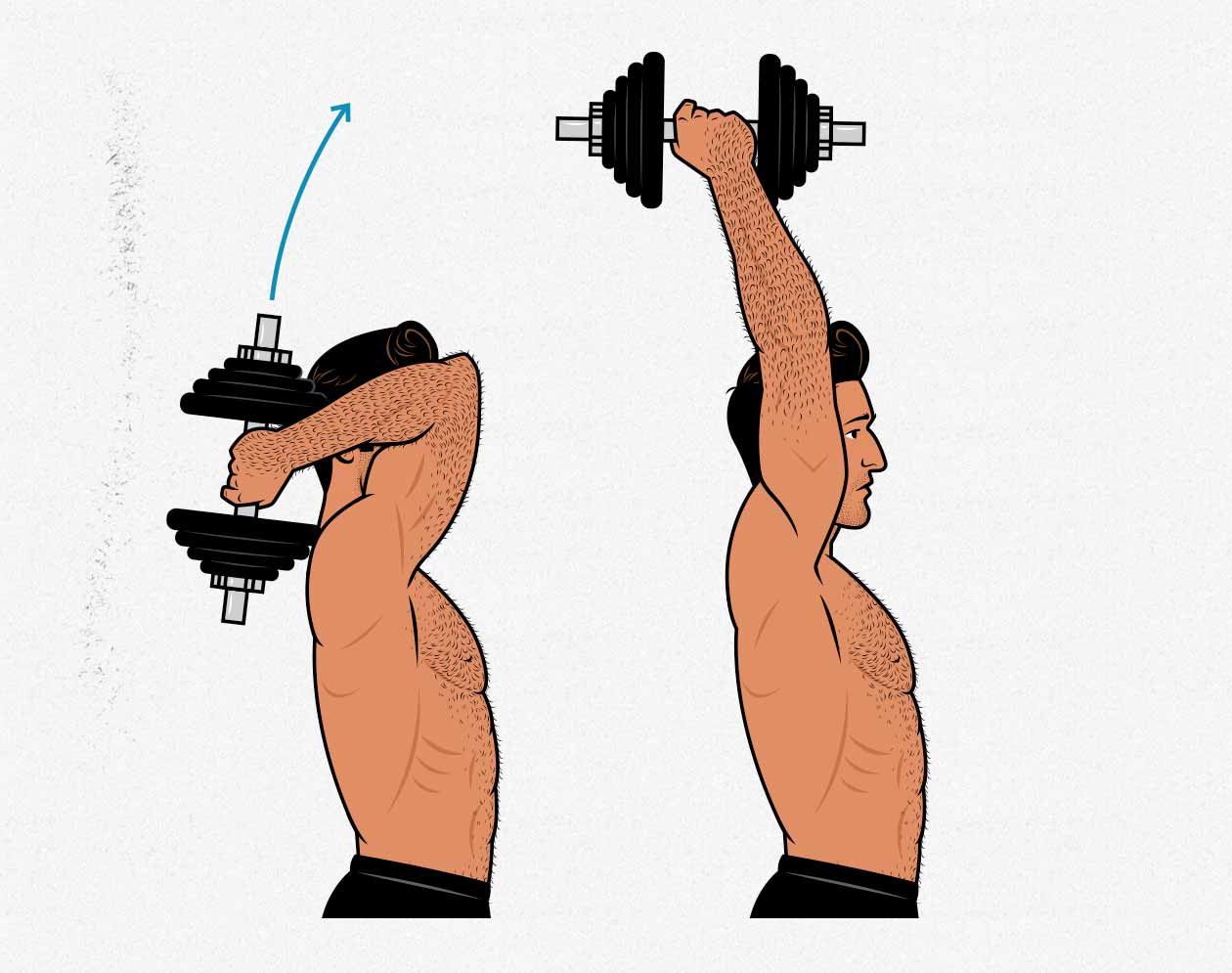

However, most of those movements have a dumbbell variation. Dumbbell pullovers can replace straight-arm lat pulldowns. Triceps pushdowns can be replaced with overhead triceps extensions. And in most of these cases, the free-weight versions do a better job of challenging our muscles in a stretched position, so they do a better job of stimulating muscle growth.

Mobility & General Strength

When I started seeing these recommendations for resistance bands popping up everywhere, I asked Marco his thoughts on using resistance bands to develop general strength and athleticism. (Marco has coached college, professional, and Olympic athletes. He’s studied under the top strength coaches in the world.

Marco told me, yes, we can build muscle with resistance bands, but it would be hard. We’d lose out on some general strength benefits. If someone had no equipment, he recommends bodyweight training instead. If they want something similar to resistance bands, they could get something without variable resistance, such as a TRX system or gymnastic rings.

There are a few reasons why free weights are so ubiquitous for helping guys get stronger and more athletic. One reason is that we stretch our muscles under load and then lift a weight through a large range of motion. This not only makes our muscles physically longer (which happens as we gain muscle) and able to stretch further (flexibility), but it also gives us strength through that complete range of motion (mobility). This makes strength and hypertrophy training great for improving our general strength and athleticism.

The problem with resistance bands is that we aren’t loading ourselves heavily in those stretched positions. That’s not only worse for stimulating muscle growth, it’s also worse for developing general strength and improving our mobility. After all, if the lift is easy at the bottom of the range of motion, then we aren’t developing as much mobility or strength there.

Mind you, any exercise can benefit us if we do it properly. Doing light exercise through a large range of motion still has many benefits. It’s just that if we have the choice, free weights are popular for strength and athletics training for a reason.

Improving Posture

Another great thing about lifting weights is, provided that we’re smart about it, it can be great for improving our posture. As with the above section, I don’t want to oversell the benefits of lifting weights or overstate the harms of having poor posture—plenty of people have poor posture and never appear to suffer from it.

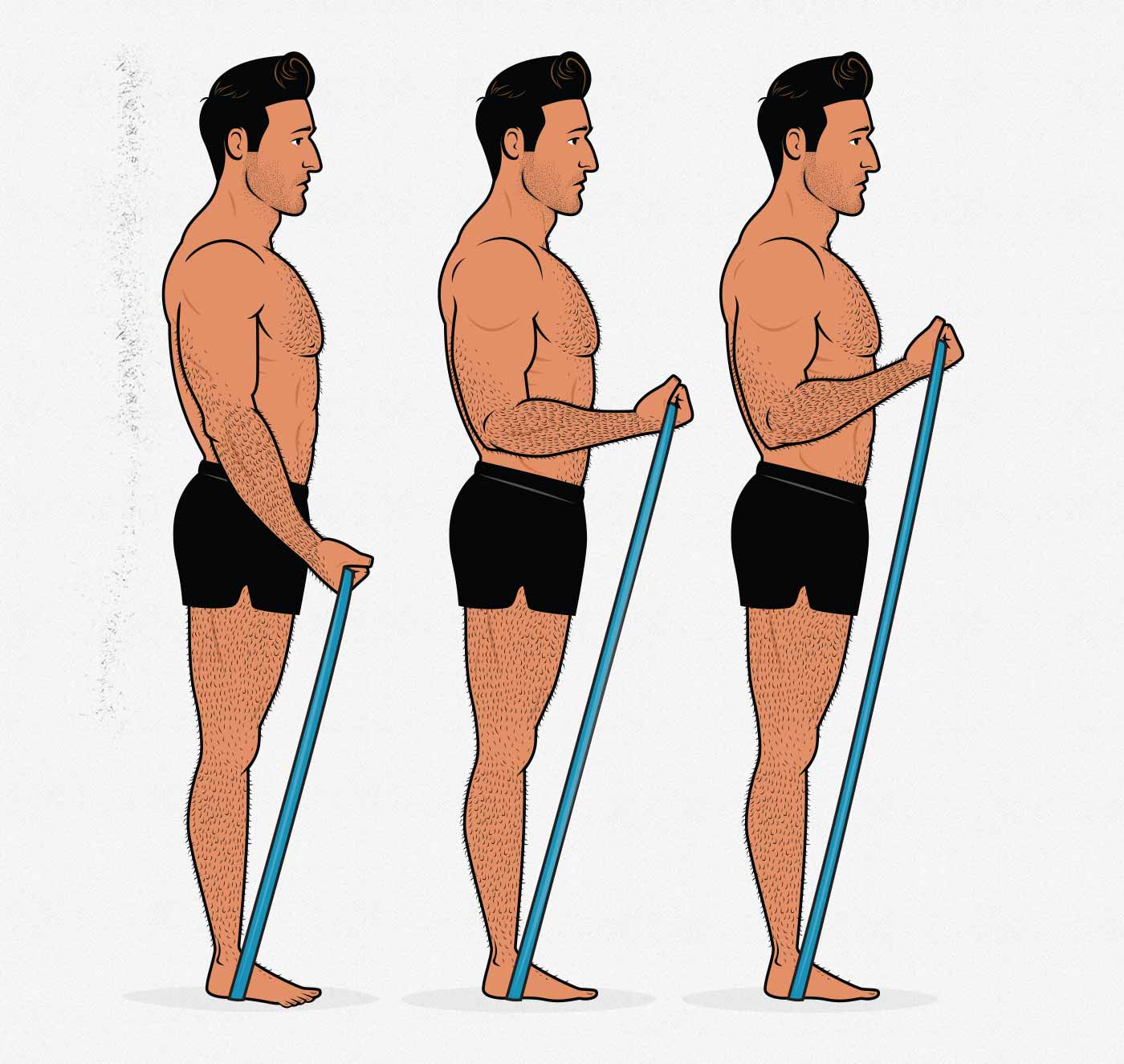

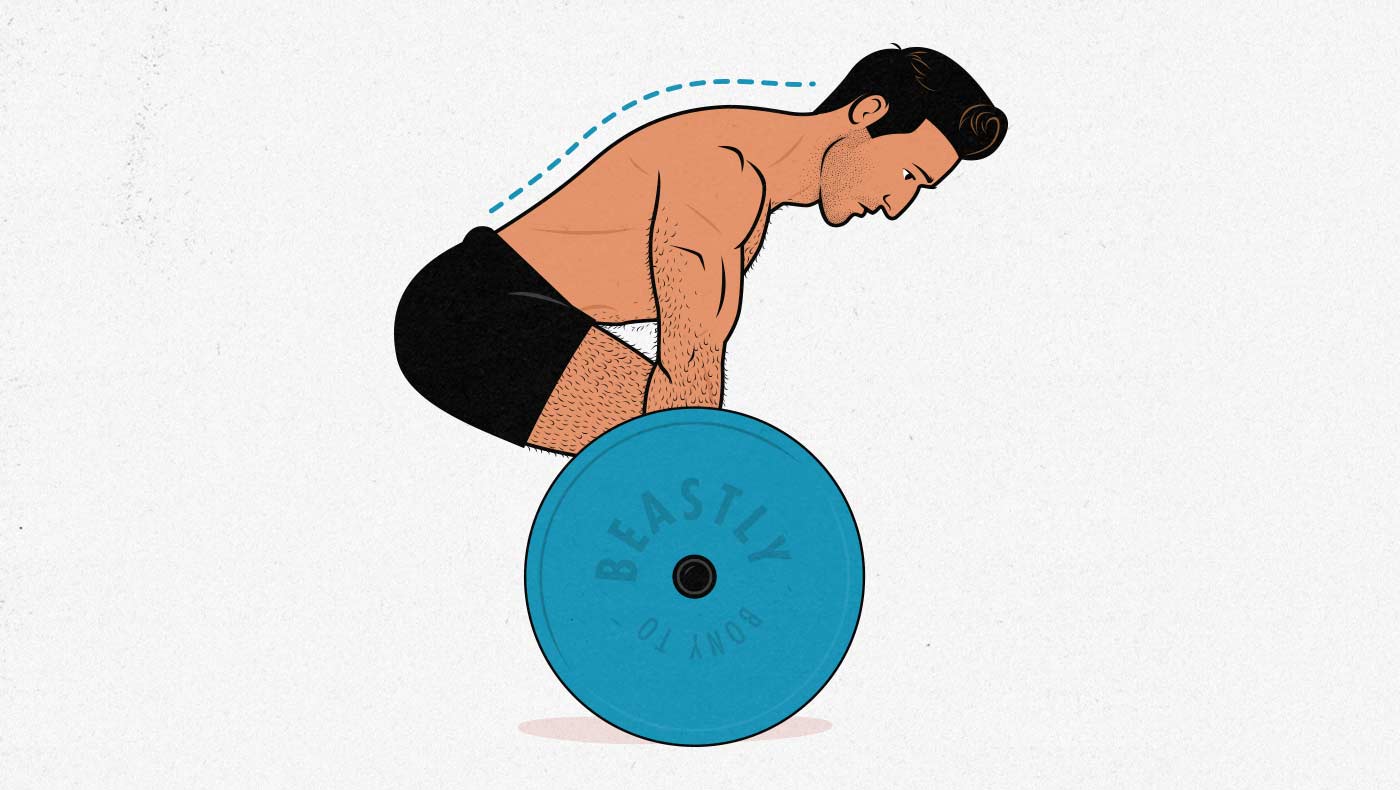

Even so, I like how over the course of gaining fifty pounds of muscle, my back gradually straightened out, my gut stopped sticking out, and my head stopped jutting forward. Why did I get those postural improvements? Because when we deadlift, front squat, and even do biceps curls, our postural muscles need to hold us in the proper position, which strengthens our abs, obliques, spinal erectors and the myriad other muscles that hold us upright.

This may not be the case for everyone, but it seems we have poor posture because our postural muscles are too weak. When we strengthen those postural muscles, the problem fades.

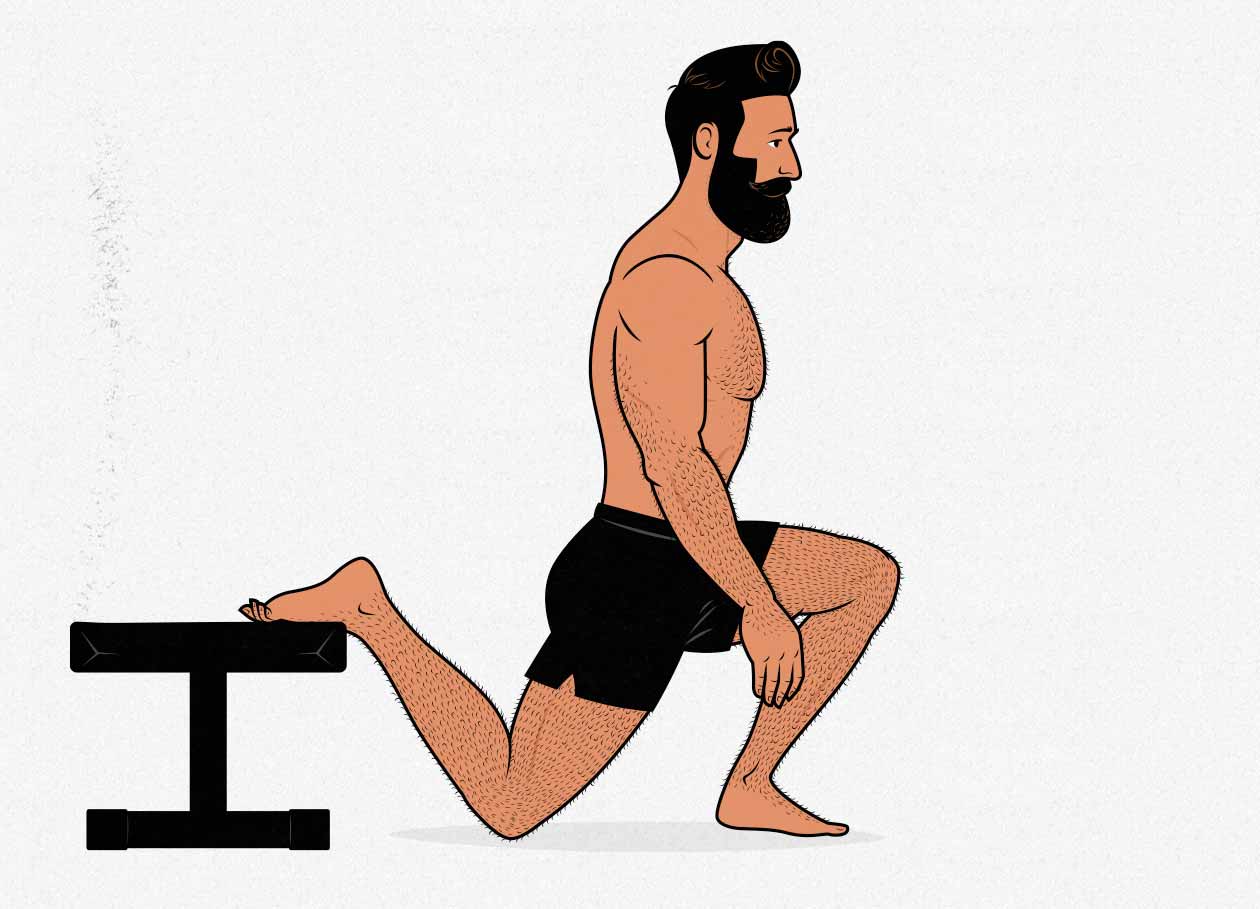

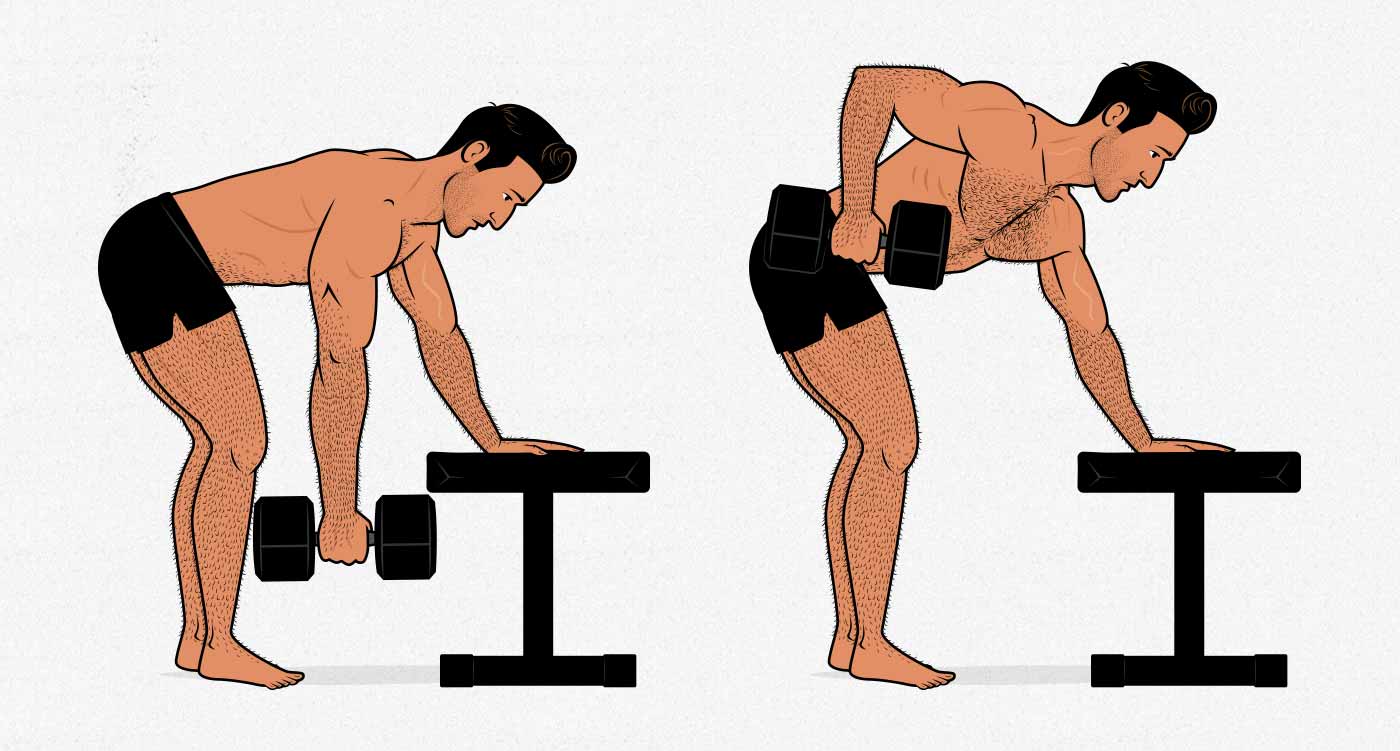

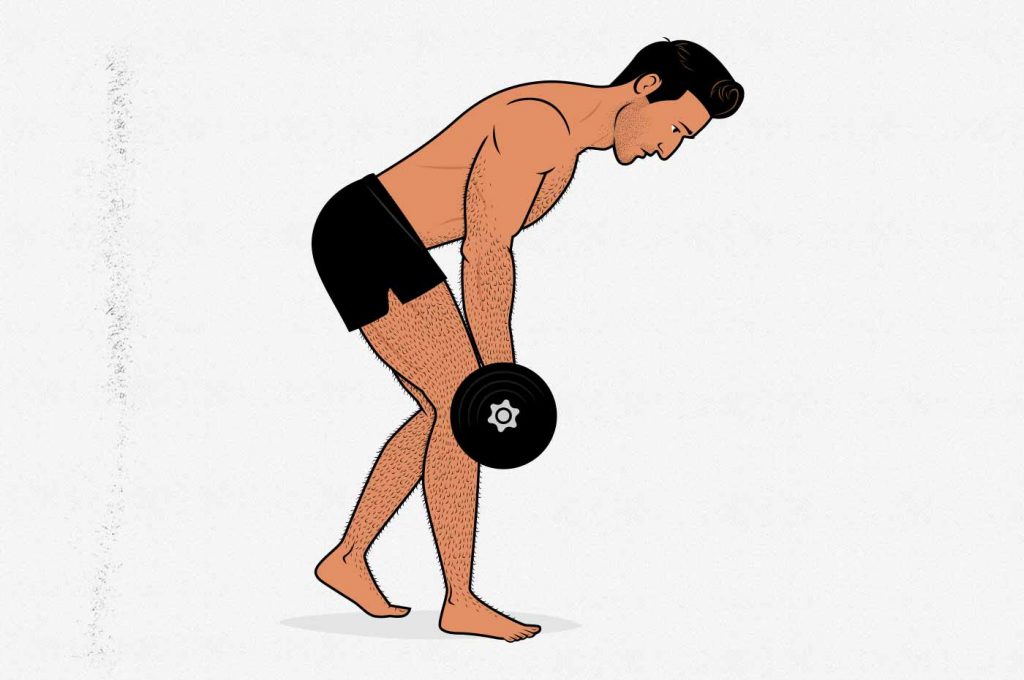

A barbell is nice, but we don’t need one. If we have a reasonably heavy dumbbell or two, we can do all of those same movements, just in higher rep ranges or while training one limb at a time. For example, we can swap out heavy conventional deadlifts for split-stance Romanian deadlifts while holding a dumbbell in each hand:

Even though the dumbbell Romanian deadlift is quite a bit lighter than a barbell deadlift, our spinal erectors and other core muscles must work for twice as long, giving them a fairly good stimulus.

The next question, then, is whether resistance bands will give those same postural benefits. They might, but perhaps not to the same extent. With resistance bands, the lift is only heavy at the very top, often when the load on our spinal erectors is the lowest (as with the deadlift). Plus, most of the range of motion is easy on our postural muscles, meaning there’s less overall work done with every rep.

The Advantages of Resistance Bands

Accessibility & Affordability

There are a few obvious benefits to resistance bands. They’re cheaper and more portable than free weights, and they allow us to do a ton of different exercises from the comfort of our living rooms. This makes them a nice addition to a bodyweight workout routine. This doesn’t necessarily make them better than free weights, but it does make them better than nothing. And again, perfection isn’t needed to build muscle. If we challenge our muscles, they will grow.

Pump Training

Another thing that resistance bands are famous for is that they make it easy to do metabolite training. Metabolite training is when you lift in higher rep ranges (12–40 reps per set) while keeping constant tension on your muscles (often doing partial reps), using short rest times between sets. This floods our muscles with metabolite-filled blood, gives us a muscle “pump,” and increases our production of local growth factors and hormones (such as growth hormone).

Dr. Brad Schoenfeld proposed that metabolite “pump” training stimulates muscle growth via metabolic stress (study). The potency of that pathway has been questioned lately, but there’s no doubt that it can provoke muscle growth.

The Hormone Hypothesis

When discussing metabolite training, we should also talk about the hormone hypothesis. This is the idea that if we train in a way that increases our production of certain hormones, such as growth hormone, we can build muscle more quickly. Recent research shows that this probably isn’t the case. There doesn’t seem to be a connection between growth hormone and muscle growth, even when researchers give study participants extremely high doses.

Furthermore, doing heavier sets of 6–12 reps, easing tension between reps, and taking longer rest periods between sets seems to work just as well for building muscle—sometimes better (study).

Can Resistance Bands Stimulate MORE Muscle Growth?

Moving onto the more scrupulous claims, there’s one resistance band company claiming resistance bands stimulate THREE TIMES as much muscle growth as free weights. The first problem with that claim is that they reference a study on accommodating resistance, which is not the same thing as resistance-band training (as covered above). The bigger problem is that the study states: “while lean body mass was not significantly different between groups, both groups did significantly increase their lean body mass over the course of the study.”

The study proves the opposite point. It found that free weights stimulate muscle growth whether we add resistance bands.

Research Comparing Free Weights vs Resistance Bands

We have a few reasons to think resistance bands might not be ideal for building muscle. However, it’s hard to say any of this with certainty. Resistance bands don’t seem to have ever been considered very seriously for building muscle (outside of physiotherapy).

Most resistance-band research doesn’t relate to muscle growth. There’s research looking at accommodating resistance, where free weights are combined with resistance bands, but that’s entirely different—the vast majority of the load comes from the free weights. And there’s also EMG research looking into muscle activation with resistance bands versus free weights, but that’s useless here because EMG favours exercises that are harder at shorter muscle lengths, which isn’t ideal for building muscle. Finally, there are studies comparing resistance bands with isometric dumbbell lifts, but that’s not how people lift weights (because it’s not as good for building muscle).

Training with resistance bands feels harder. What’s interesting is that in a lot of these studies looking into resistance bands, the participants said that they needed to put in a lot more effort to stimulate their muscles with resistance bands. Maybe that’s because they’re less stable, or maybe it’s because of the unnatural strength curve, but the research does show that building muscle with resistance bands feels harder (study, study).

We also have some research showing that resistance bands aren’t as good at stimulating our prime movers. For example, in a bench press, resistance bands aren’t as good at stimulating our chests. We’ve already talked about why that might be. Our chests grow best when loaded in a stretched position, and resistance bands don’t do that. It’s our shoulders and triceps that wind up bearing more of the load.

Another thing that keeps coming up in the research is that resistance bands are inherently less stable. As a general rule of thumb, stable training is better for building muscle because it allows us to focus more on moving the weight and less on stabilizing it. Mind you, dumbbells demand more of our stabilizer muscles, too, and are just as good at stimulating muscle growth as barbells (article), so I’m not sure if this would actually have an impact on hypertrophy. Mind you, resistance bands are much less stable than dumbbells.

We know that free weights are great for building muscle, and we can say that with certainty—they’re the industry standard. There are also good reasons to think that resistance bands wouldn’t be as effective, but it’s hard to say how much or whether it matters.

The Best Resistance Bands for Building Muscle

Resistance bands may not be totally ideal for building muscle, but they’re quite convenient. Maybe you want to buy some anyway. There are a few different types of resistance bands, all somewhat similar. After all, they all have variable resistance, where the resistance increases the further you stretch them. Still, some bands are notably better than others.

The cheapest resistance bands tend to be tubes with handles at the ends. However, those resistance bands are known to snap, sending the handles flying and taking out eyes and TV screens. Most of us have a spare eye, but we don’t all have spare TV screens. Better to get the more durable looped bands.

The thicker looped bands can be used for accommodating resistance, assisted chin-ups, banded deadlifts, and other heavier movements. The lighter ones can be used for biceps curls, triceps extensions, lateral raises, and banded push-ups. Of these, I think Rogue’s Monster Bands are the best quality. These are the ones I got.

As a bonus, Rogue Fitness has other valuable home workout tools. They’ve got a parallette set for doing deficit push-ups, handstand push-ups, and dips, as well as a variety of pull-up bars and gymnastics rings that you can do chin-ups with. Their products aren’t cheap, but they’re great.

*These are affiliate links. But even before becoming an affiliate, I bought my entire barbell home gym from them. Rogue’s stuff is great.

With that said, you don’t need to get this specific brand of resistance band; just try to get this specific type of band. Look for the sturdy looped bands, as shown in the photo above. These are the same bands you’ll see from popular companies like UnderSun Fitness.

2023 Update: Biceps Growth

A new study by Pedrosa and colleagues found greater biceps growth when challenging the biceps at the bottom of the range of motion than at the top (study). This lines up with the evidence we covered earlier in the article. Again, this hints that resistance bands may not be ideal for stimulating muscle growth.

Conclusion

You can build muscle with resistance bands. If that’s all you have access to, you may as well take advantage of them. However, it’s quicker and easier to build muscle with free weights.

Alright, that’s it for now. If you want more muscle-building information, we have a free bulking newsletter for skinny guys. If you want a full foundational bulking program, including a 5-month full-body workout routine, diet guide, recipe book, and online coaching, check out our Bony to Beastly Bulking Program. Or, if you want a customizable intermediate bulking program, check out our Outlift Program.