Should Beginners Lift to Muscle Failure?

As a new lifter trying to gain muscle size, how close to failure should you be lifting? Some argue that beginners should stop shy of failure, leaving a few reps in reserve (RIR). There’s some wisdom to that advice. It allows beginners to better practice their technique, reducing the risk of injury.

Others argue that beginners should take their sets all the way to muscular failure, ensuring they’re pushing themselves hard enough to stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth with every set. But does taking a set all the way to failure actually stimulate more muscle growth? Let’s take a look at the research.

Finally, not every lift is the same. Some suit training to failure better than others. So, it’s not as simple as saying that a beginner should always train to failure or avoid training to failure. It often depends on the specific lift.

What Is Training to Failure?

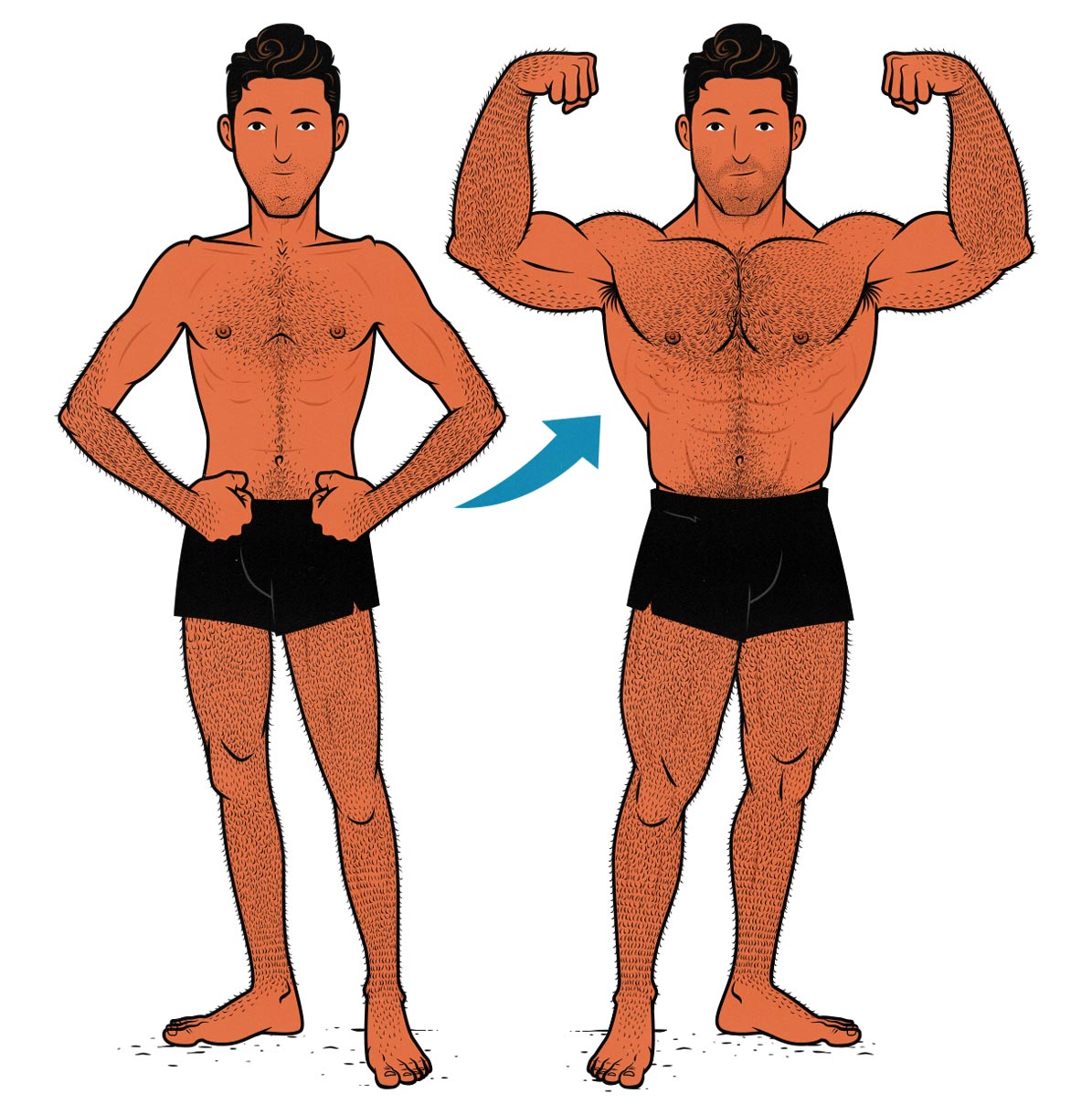

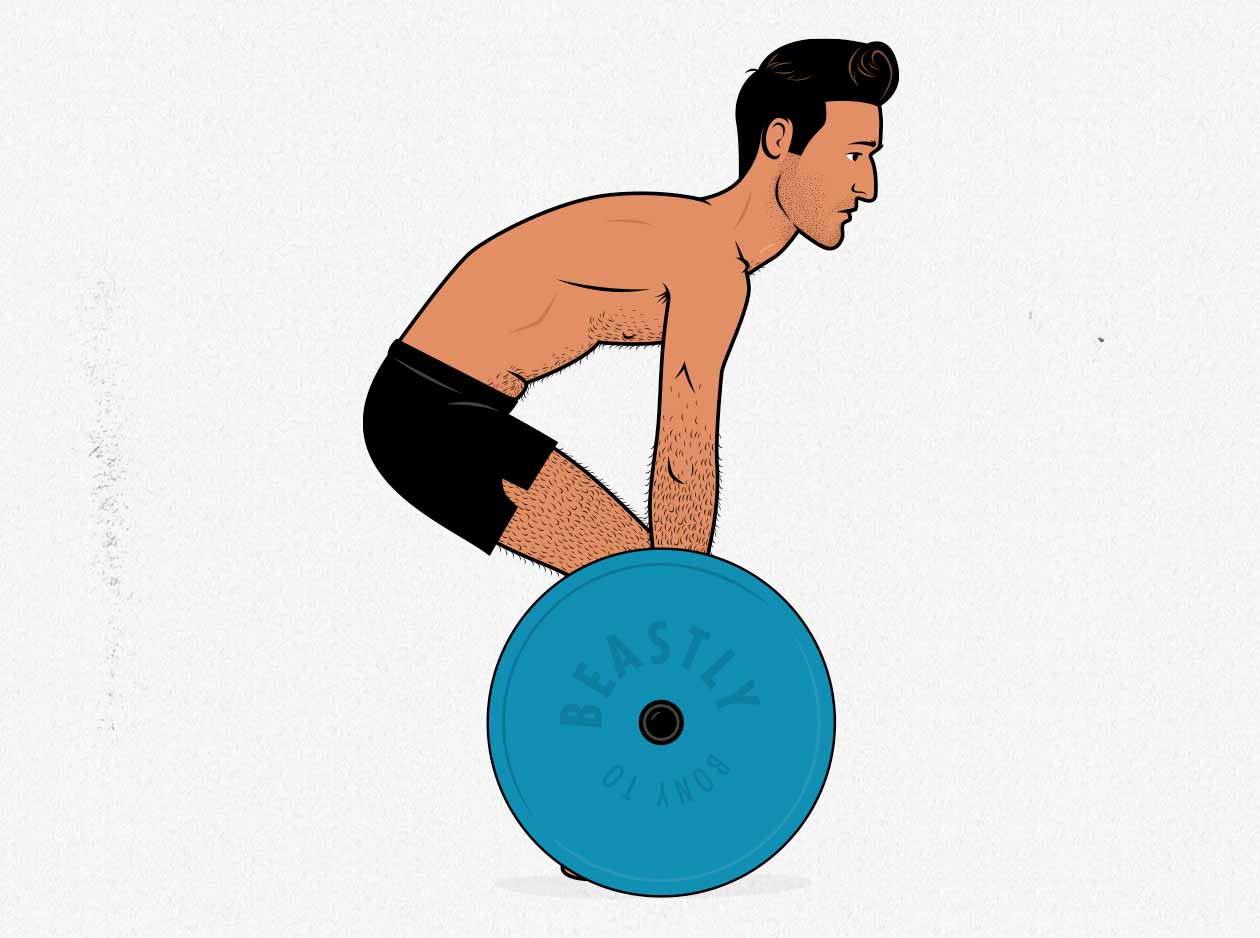

There are a few ways of defining failure. The most objective way of defining failure is absolute failure—the point where you can no longer move the weight. If you simply cannot lift the barbell off the ground, no matter how much you bend your lower back, you’ve hit absolute failure. This type of failure is often used in lifting research because it allows the researchers to standardize their results. They have the participants lift until they can’t lift anymore. Simple.

The downside of training to absolute failure, though, is that it can be needlessly risky. By the time you’re deadlifting with a rounded lower back, it means that either your hips are past muscular failure, and so you need to improve your leverage by shortening your lever, or it means that your spinal erectors have passed failure and have given out. Either way, you’re multiplying the shear stress on your spine, and the muscles you’re trying to grow are already past failure anyway.

That’s why most bodybuilders, strength trainees, and casual gymgoers use what’s called technical failure, where you stop lifting when your form starts to break down. It’s less objective, yes. Different people will stop their sets at slightly different points. But it’s also quite a bit safer because, even on the final rep, your lifting technique is still quite good.

There’s also the idea of stopping just shy of failure. You grind out a final good rep, realize you can’t get another, and stop your set there. You haven’t actually hit failure, but you’ve done as many reps as you can. Instead of doing, say, 10.3 reps, failing a third of the way up, you’ve done 10 reps. This is even more subjective. Some people will stop their set when it becomes painful or hard, not when they’re actually flirting with failure. But again, it has the advantage of lowering the risk of injury and reducing fatigue.

A good rule of thumb is to stop your set when you can’t lift with proper technique (or a little bit before).

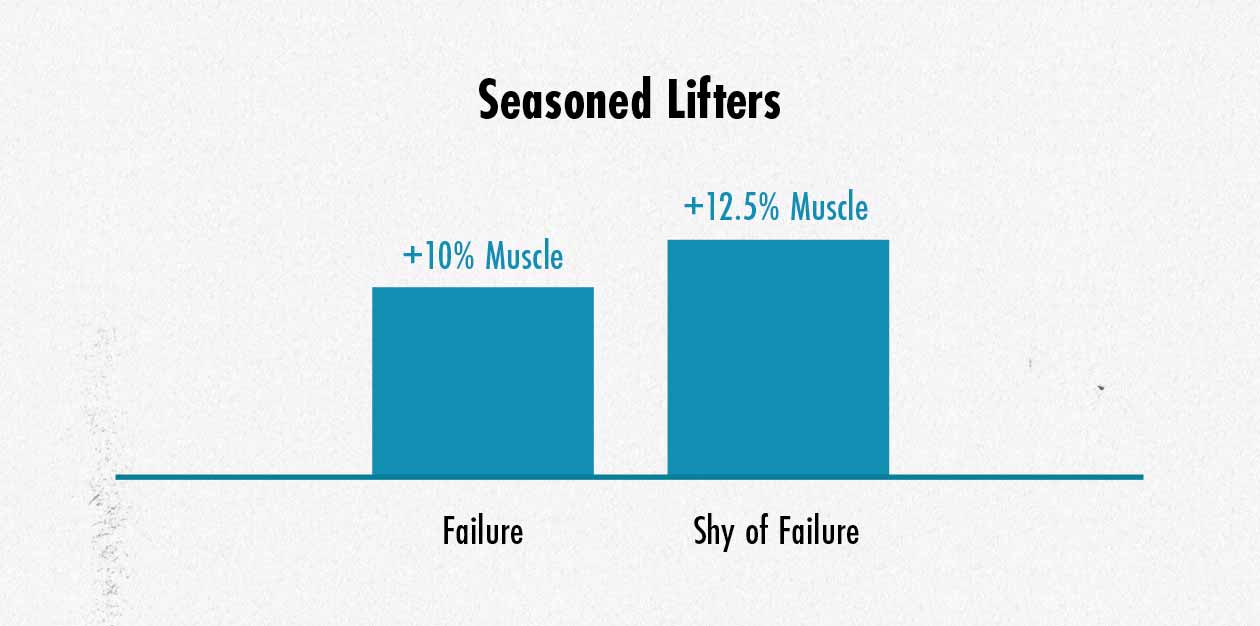

Intermediate Lifters Benefit from Avoiding Failure

Recent research quite clearly shows that for more advanced bodybuilders, there’s usually a benefit to stopping sets just shy of failure (study, study, study, study, study), leaving somewhere between 0–3 reps in reserve. They’re lifting with good technique, they’re lifting heavy weights, and they’re great at contracting their muscles. As a result, they can stimulate muscle growth quite well without needing to lift all the way to muscular failure.

In fact, by stopping short of failure, they cause less muscle damage, generate less fatigue, and retain more of their strength, allowing them to recover more quickly between sets and between workouts, allowing them to get more quality work in. As a result, they actually wind up stimulating more muscle growth by stopping shy of failure.

Now, that isn’t to say that intermediate lifters should never lift to failure. If their technique is good, they’re using a safe setup, and they know to stop before their form degrades to a dangerous degree, then there’s little risk of taking sets to failure. It may even make sense to take some of their final sets to failure to make sure they’re really pushing themselves hard enough. Or perhaps they wish to use a training style that suits pushing to just shy of failure, such as reverse pyramid training.

So, with intermediate lifters, we have a situation where it’s often better to stop their sets just shy of failure, but there’s little harm in pushing all the way to failure. There’s no real wrong answer. With beginners, though, it’s much trickier.

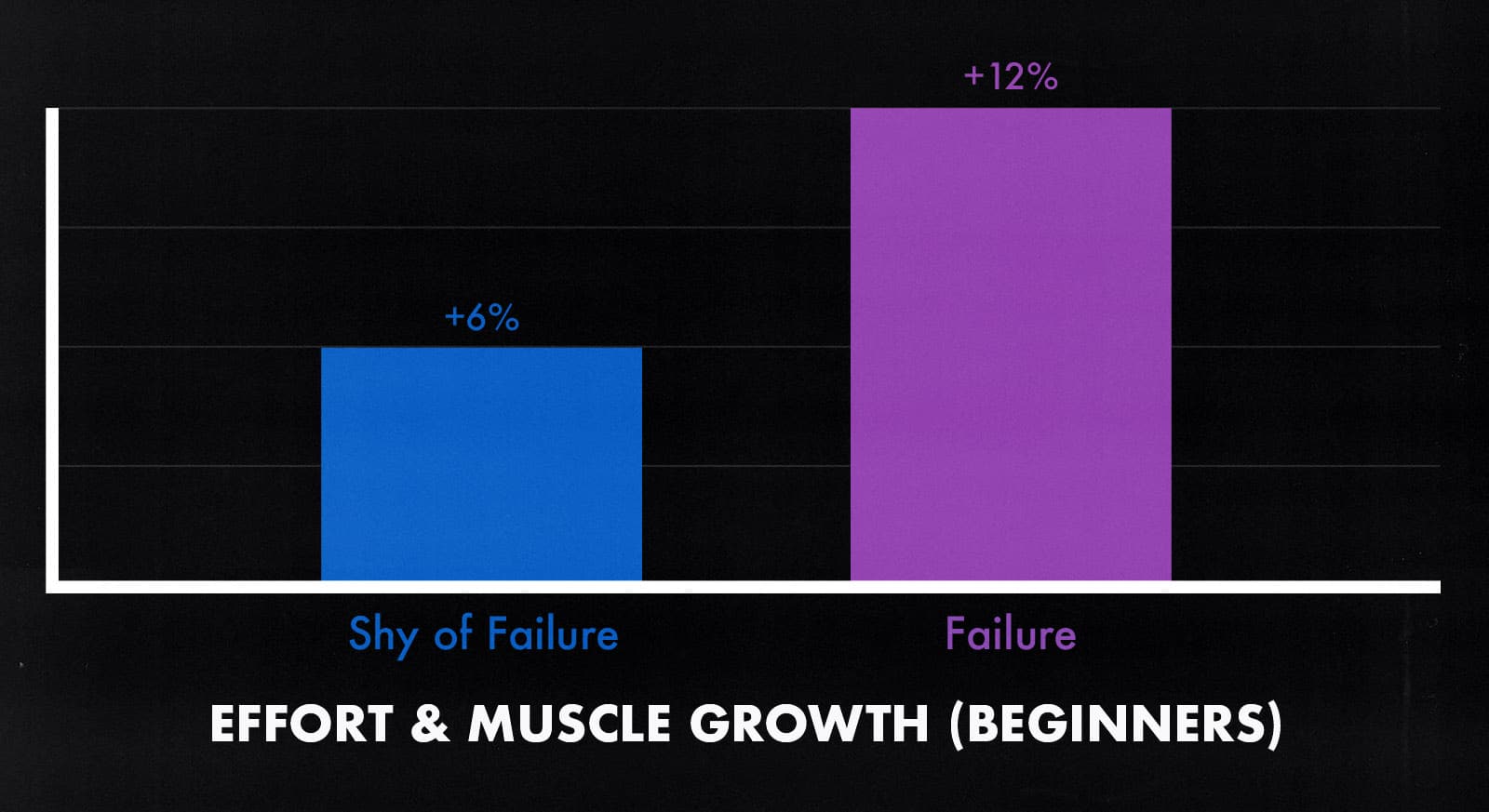

Beginners Gain Muscle Faster When Lifting to Failure

Beginners aren’t lifting with great technique, their weights aren’t very heavy yet, and they aren’t very good at contracting their muscles. As a result, by stopping too far away from failure, they might fail to adequately challenge their muscles, reducing the amount of muscle growth they stimulate with each set.

The research reviewer, Greg Nuckols, pooled the data from all the studies on training intensity on beginners, and he found that training to failure caused twice as much muscle growth (Sampson, Goto, study, Nóbrega).

That’s an awkward truth because when beginners take their sets all the way to failure, they increase their risk of injury. Most of these injuries are fairly minor. A pulled muscle in the neck, a sore lower back, and some elbow pain. But still, that’s often enough to turn people off of lifting, and even if it isn’t, it can introduce some serious delays.

Plus, training to failure as a new lifter often means grinding out a few ugly reps at the end of each set—crooked torsos, lopsided shoulders, throbbing neck veins, and rounded lower backs. Practicing poor technique can make it harder to improve their skill as lifters, keeping them stuck in the beginner stage for longer.

So, should beginners take their sets to failure to get some extra short-term muscle growth? Is it worth the risk? To the skinny guy desperate to build muscle, it often seems like it might be worth it. It’s not until they get injured that they regret it. And not every reckless lifter gets injured, so there’s the allure of a good gamble.

When Should Beginners Lift to Failure?

It presents us with a dilemma. As experts specializing in helping skinny guys bulk up, we want to help you build muscle as quickly as possible. We were skinny ourselves. We remember what it’s like to feel desperate for growth. But at the same time, it’s our job as experts to help you avoid the mistakes we made, to teach you how to build muscle safely, to help you become skilled lifters.

Fortunately, we can get the best of both worlds:

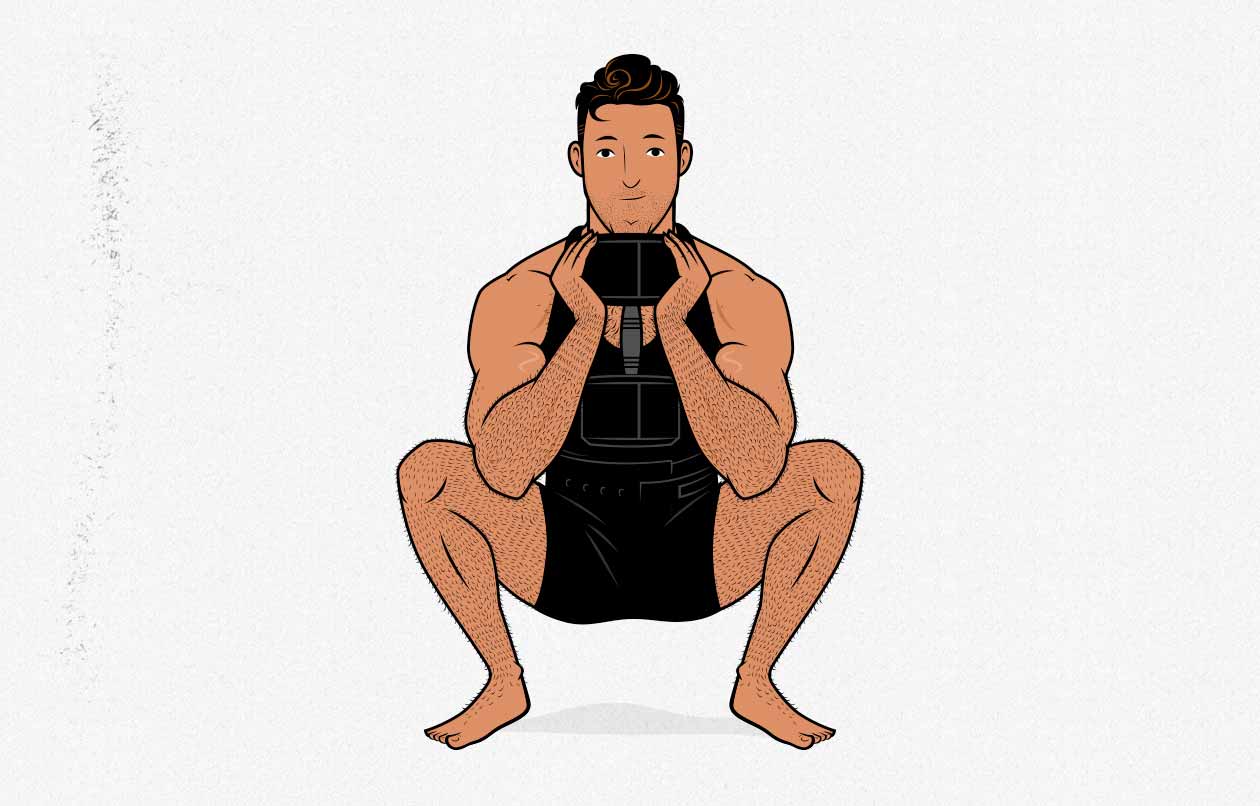

- Stop shy of failure with our compound lifts. By stopping our compound lifts shy of failure, we can reduce our risk of injury, better improve our technique over time, and recover more quickly between sets and between workouts. For example, we might want to leave 2–3 reps in the tank when doing our goblet squats.

- Push our muscles harder with isolation lifts. If we choose isolation lifts that are simple and safe, we can take our sets closer to failure with very little risk of injury, and we can give our muscles that final bit of stimulation they need to grow at full speed. For example, we might want to take our final set of biceps curls all the way to muscle failure.

There are plenty of exceptions, but stopping shy of failure on compound lifts and then pushing harder on isolation lifts works quite well as a general rule of thumb. I asked Greg Nuckols—the researcher who parsed this data on training to failure—what he thought of that approach, and he concurred:

For training new lifters, I personally like to keep them far from failure on compound lifts, with the goal of teaching good technique, but also choosing single-joint exercises that will let them go to failure safely, getting them a bit of a pump.

Greg Nuckols, Monthly Applications in Strength Sport (MASS)

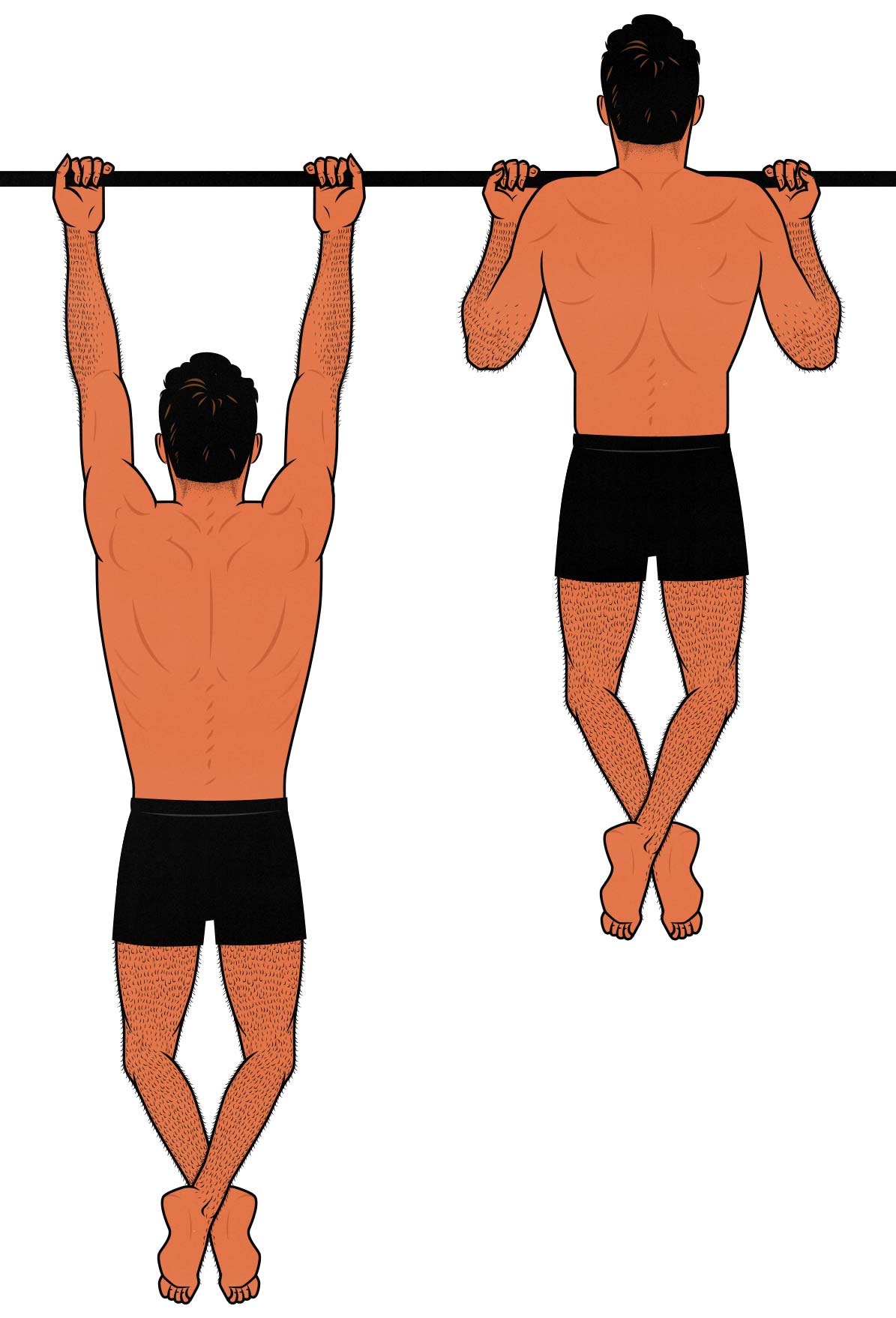

Some compound lifts can be taken to failure with little risk, too. Chin-ups, for instance. Beginners are often unable to do full chin-ups, so they often benefit from jumping up to the bar and lowering themselves back down. That means that, technically, they’re doing cheat reps—they’re lifting beyond failure. But even so, the risk of injury is still very low, and any degradations in technique don’t tend to cause problems with learning the lift.

The same is true for beginners who can do full chin-ups. They often do fine by stopping when they can no longer bring their chins (or chests) to the bar. By doing that, they’re going all the way to failure, but again, there’s little risk of any adverse outcome.

Here are some lifts where it’s often wise to stop shy of failure:

Here are some lifts that suit training to failure:

- Chin-ups

- Biceps curls

- Triceps extensions

- Lateral raises

- Leg extensions

- Leg curls

- Machine flyes

- T-bar rows

Also, keep in mind that when we’re talking about lifting to failure, we’re talking about lifting to technical failure. Once your form degrades, the set is done. But with some of these safer isolation lifts, it can make sense to push all the way until we notice our form start to degrade. (Keep in mind that as a beginner, don’t expect perfection. Aiming for “good” is good enough. Your technique will improve over time.)

Becoming an Intermediate Lifter

As you gain more confidence lifting weights, your newbie gains start to slow down, and you start to move out of that beginner phase; that’s when you might want to start pushing your compound lifts a little harder. For example, instead of leaving 2–3 reps in the tank on your squats, keep adding weight to the bar, keep trying for more reps, and see what happens as you gradually push yourself harder. You shouldn’t always be training to failure, but you should know what it feels like, get used to grinding out slow reps, and start improving your ability to gauge how far away from failure you’re actually lifting.

But overall, you’ll still want to leave some reps in reserve on the compound lifts, and you’ll still want to push your isolation lifts harder. It’s just that now you’re getting full stimulation out of your compound lifts.

Remember, training to muscular failure causes a disproportionate amount of muscle damage. This means you’ll need to go through a long recovery process before you can train those muscles again. Historically, muscle damage was thought to cause muscle growth, but now most hypertrophy research shows that muscle growth is caused by mechanical tension and metabolic stress, not muscle damage. Furthermore, excessive muscle damage means that your body will need to invest more resources into repairing that damage, leaving fewer resources available for constructing new muscle tissue (study).

There’s another problem with always training to failure, too. The more you damage your muscles, the longer it will take them to recover, and the less frequently you’ll be able to train them. A workout only stimulates 24–72 hours of muscle growth, so if you’re going more than a couple of days between workouts, you’ll leave muscle growth on the table. That’s why full-body workouts tend to stimulate more muscle growth than push/pull/legs split routines.

Why You Should Sometimes Lift to Failure

Our goal with our training is to challenge ourselves without overdoing it. Leaving a couple of reps in the tank helps us avoid overdoing it, but we must also ensure we’re lifting hard enough to truly challenge ourselves. Your workouts should be challenging; you should always be fighting to add weight or reps to your sets, you should need a minute or two of rest between sets, and you should definitely feel your muscles being stressed by the weights that you’re lifting.

You can run into problems if you get into the habit of always pushing yourself to failure, especially if you’re following routines that recommend leaving a couple of reps in the tank. By always overdoing it, you can increase your risk of getting sick, you may find yourself crippled by muscle soreness, and it can even start to harm your sleep. Training is supposed to be a fountain of youth, not a preview of what it feels like to live in a retirement home. It’s important to balance stress with recovery.

But it’s equally important to make sure that your training is challenging enough to stimulate muscle growth, otherwise you may find that as soon as you become an intermediate lifter, your muscle growth grinds to a halt—you hit a plateau. To make sure that you’re challenging yourself, you might want to experiment with taking some of your final sets to failure some of the time. By occasionally taking your final sets on an exercise to failure, you’ll learn how close to failure you’re actually going. You might be surprised to learn that you’re stopping further away from failure than you thought you were.

For example, perhaps you’re trying to leave around two reps in the tank, but when you take your set to failure, you find that you can eke out five more reps. In that case, you need to learn to push yourself harder. This is common with exercises like the squat, where getting anywhere close to failure can require some real grit, especially as you continue to get stronger.

The opposite can happen, too. Perhaps when you take your set to failure, you realize that you can’t get any extra reps. This is common with exercises like the bench press and overhead press, where people can often get quite close to failure before the exercise really challenges them.

Now, with this idea of taking some sets to failure, always make sure that you’re doing it safely. With a set of curls, there’s no real risk of injuring yourself by pushing yourself harder. But if you’re going to take a set of squats to failure, ensure you’ve got your safety bars set up. The same is true with the bench press. Get your safety bars set up. (Here’s how to set up your safety bars for the bench press.)

Remember that taking your sets to failure is mainly a learning tool. It’s not the ideal way to train all of the time forever, it’s just a way to gauge how many reps you’re leaving in the tank, a chance to learn what it’s like to push yourself, and a way to make sure you’re pushing hard enough (especially on isolation lifts).

Summary

As a beginner, taking sets closer to failure stimulates more muscle growth. However, it also increases the risk of injury, causes more muscle damage, and makes it harder to improve lifting technique. As a result, it’s usually wise to stop a couple of reps shy of failure.

However, because beginners grow faster when they push themselves harder, it’s often smart to include some simple isolation lifts in your routine that allow you to lift all the way to failure. For example, if you’re eager to grow your biceps, include some biceps curls in your program and take some of those sets to failure—perhaps the final set of each isolation lift. Not only will that ensure adequate muscle stimulation, but it will also help you learn what failure feels like and how to keep a precise number of reps in reserve.

As you gain experience, actually hitting failure becomes less important. You’ll build muscle mass more quickly if you stop 2–3 reps shy of failure. That will put more emphasis on mechanical tension and metabolic stress and less emphasis on muscle damage.

As a result, you’ll be able to build muscle more quickly because fewer resources will be wasted on muscle repair. You’ll also be able to train your muscles more frequently, leading to even more muscle growth.

There’s nothing wrong with continuing to push some of your isolation lifts closer to failure, though, so long as it doesn’t leave you crippled by muscle soreness during your next workout.