How Big Should Men Build Their Legs?

What’s the ideal male leg size? How often should we be squatting and deadlifting? How much emphasis should we put on leg training if our goal is to improve our health, general strength, and appearance? What’s interesting is that there are popular views at opposite ends of the spectrum:

- Some aesthetics-oriented approaches have us spending more of our time doing upper-body training: more incline bench pressing, chin-ups, overhead pressing, and biceps curls. If lower-body training is included at all, it’s often lighter stuff, such as one-legged squats and Romanian deadlifts.

- Some strength training programs tell us to focus on getting stronger at the Big Three lifts: the squat, bench press, and deadlift. In those circles, it’s common for every workout to start with a few sets of strenuous back squats. Is that a good way to build a strong and attractive physique?

If we’re trying to build strong, healthy, and attractive physiques, how big should our legs be? How often should we train them? And what lower-body lifts should we choose?

- Introduction

- The Benefits of Building Strong Legs

- How Big is Too Big?

- The Problem with “Big Three” Lifting Routines

- Men with Bigger Upper Bodies are More Attractive

- Bigger Upper Bodies Look More Masculine

- Our Lower Bodies Don’t Need to Be Infinitely Strong

- Upper-Body strength is Often Our Limiting Factor

- Big Legs Don’t Fit into Pants

- Squats Won’t Make Our Upper Bodies Bigger

- What’s the Ideal Leg Size?

- How Much Leg Work Should We Do?

- Which Style of Training is Best for Our Proportions?

- Key Takeaways

Introduction

So, first of all, one point that often gets lost in conversations like these is that anything is better than nothing. It’s better to do push-ups than nothing at all, even if you don’t do cardio. Expanding that to lifting weights, it’s healthy to do the bench press, overhead press, and biceps curls, even if you don’t squat or deadlift. It’s not “bad” to only do upper-body training. Some people enjoy training that way, and it’s a helluva lot better than sitting on the couch for their overall strength, health, and appearance. It’s just not as good as it could be.

Furthermore, there’s no system that we need to mould ourselves into. We aren’t powerlifters who are judged based on three lifts. We’re not bodybuilders who need to conform to certain judging criteria. So it’s okay if you never squat or deadlift. It’s also okay if you only squat and deadlift. But I think people enjoy these articles because we talk about the correct and the best way to do things.

The case I want to make in this article is that we should take a balanced approach with our lifting routines. We shouldn’t necessarily prioritize the squat over every other lift, but we shouldn’t be neglecting it, either. That’s easier said than programmed, though. How often should we squat and deadlift? How many sets should we do per workout? And does the squat always need to be the very first lift that we do?

I also want to argue that if we’re trying to build a strong and aesthetic physique, there’s more than just the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Choosing big compound lifts for our shoulders (such as the overhead press) and our upper backs (such as the chin-up) is just as important. In addition to that, if we don’t have isolation lifts for our arms (such as biceps curls, triceps extensions, and perhaps even some forearm training), our arms will likely lag behind. And even with all that, we haven’t done anything to bulk up our necks.

Finally, where does the law of diminishing returns kick in?

- When are our legs big enough to look attractive, and is there such a thing as having legs that look too big?

- When are our legs strong enough? Is squatting 225 pounds strong enough? What about 315? Most of us aren’t powerlifters, so building an ever-stronger back squat isn’t always better.

- And at what point do the general health benefits stop? If you can squat 225 for ten reps, is that good enough? Is there a point where the injury risks of squatting heavy start to outweigh the health benefits?

First, let’s go over some of the benefits of squatting and deadlifting, making a case for why they should be part of our lifting routines.

The Benefits of Building Strong Legs

Before we get into the benefits of building bigger and stronger legs, I should point out that when we’re talking about squatting and deadlifting, we aren’t necessarily talking specifically about the barbell back squat and conventional barbell deadlift. It’s true that those two lifts tend to give us the best bang for our bulk—they’re famous for a reason—but that isn’t to say that those specific variations need to be part of our lifting routines, just that we should find a way to train those general movement patterns.

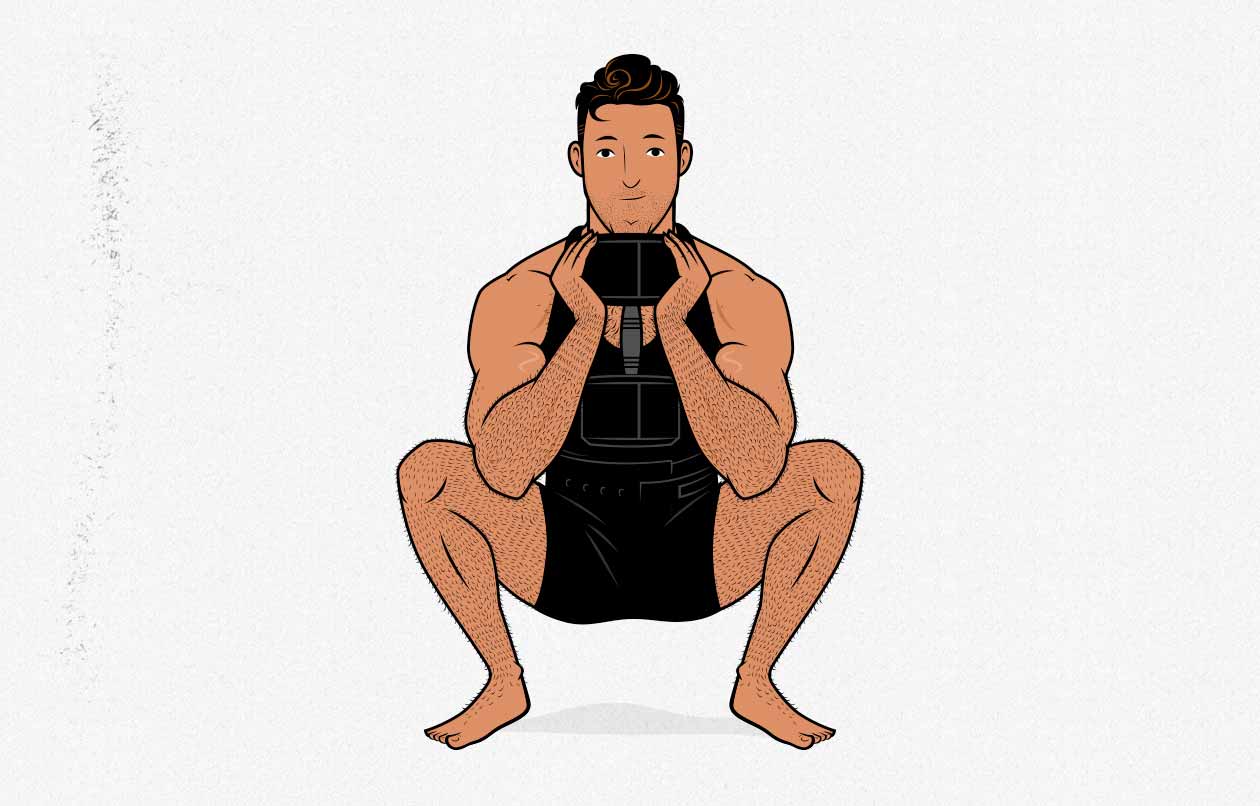

When we say “squat,” keep in mind that you can do dumbbell goblet squats instead of low-bar back squats. And when we say deadlift, keep in mind that dumbbell Romanian deadlifts count, too. You can choose the lifts that best match your circumstances and your equipment.

Squatting & Deadlifting for General Health

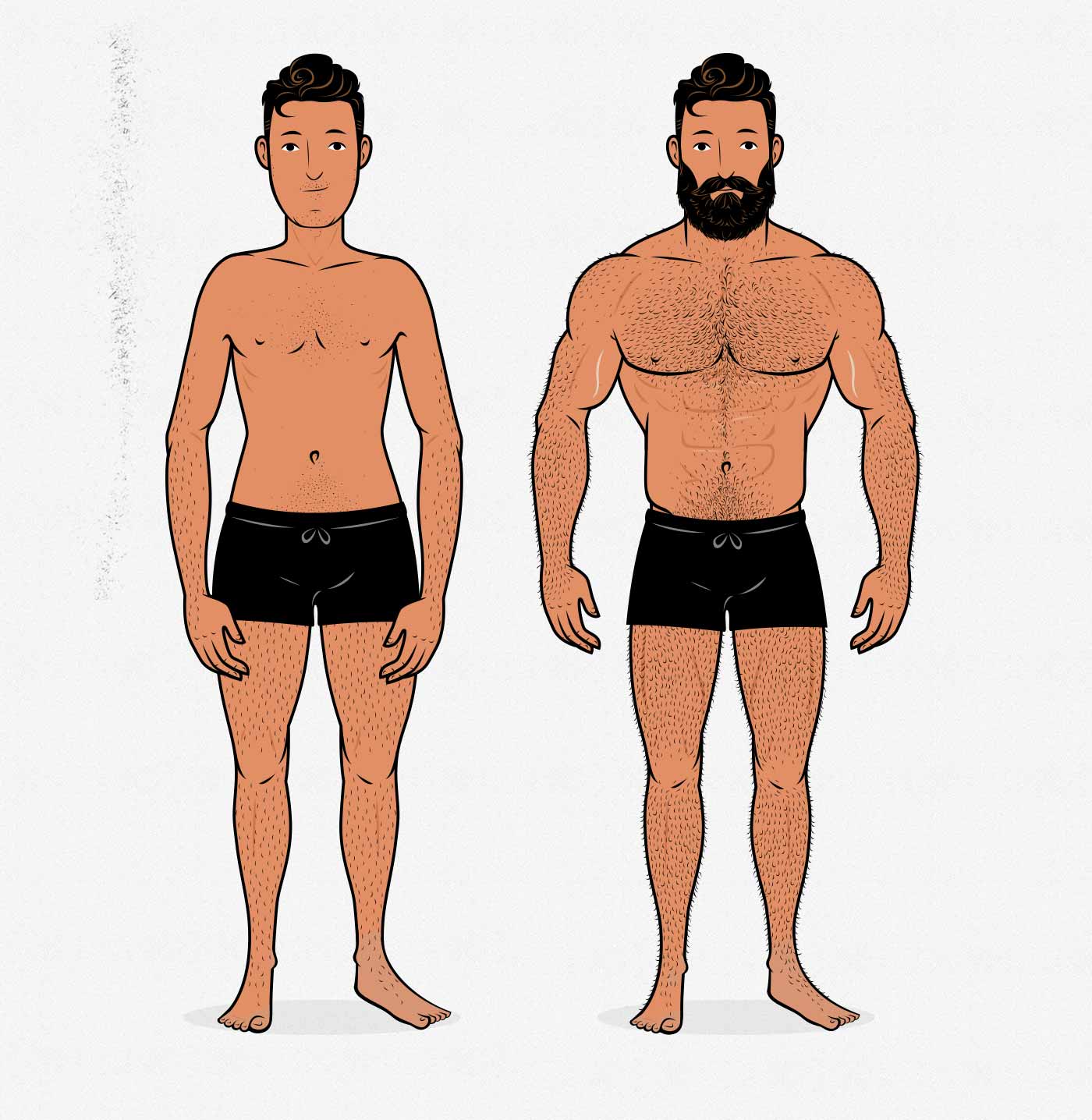

First, I should be honest with you guys. I skipped leg day. To be fair, though, I was skipping push and pull day, too. I was a graphic design student who didn’t do any cardio or resistance training, and that was a major mistake. For an idea of what that looked like, here I am participating in a university photography project:

I wasn’t really spending my evenings drinking bottles of wine in a haunted apartment, but my legs really were that small, and it’s hard to put into words how many problems that was causing me. My posture was caving in on itself, I was skinny and weak, I was unhappy with my appearance, and my cardiovascular health was so bad that I had started seeing a heart specialist on my eighteenth birthday. The doctor told me that I already at moderately high risk of having a heart attack and that if I couldn’t turn my health around, I’d be on statins by thirty.

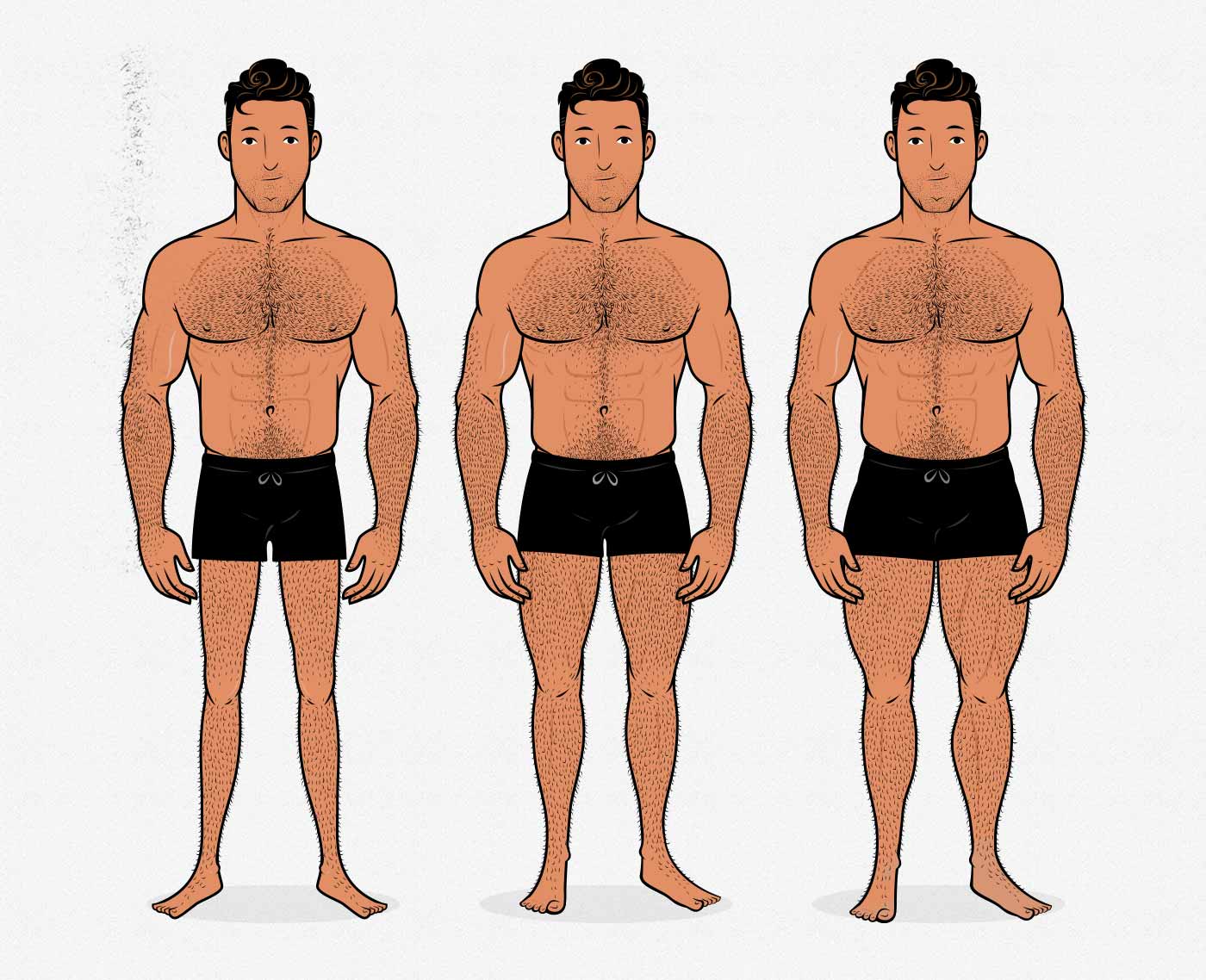

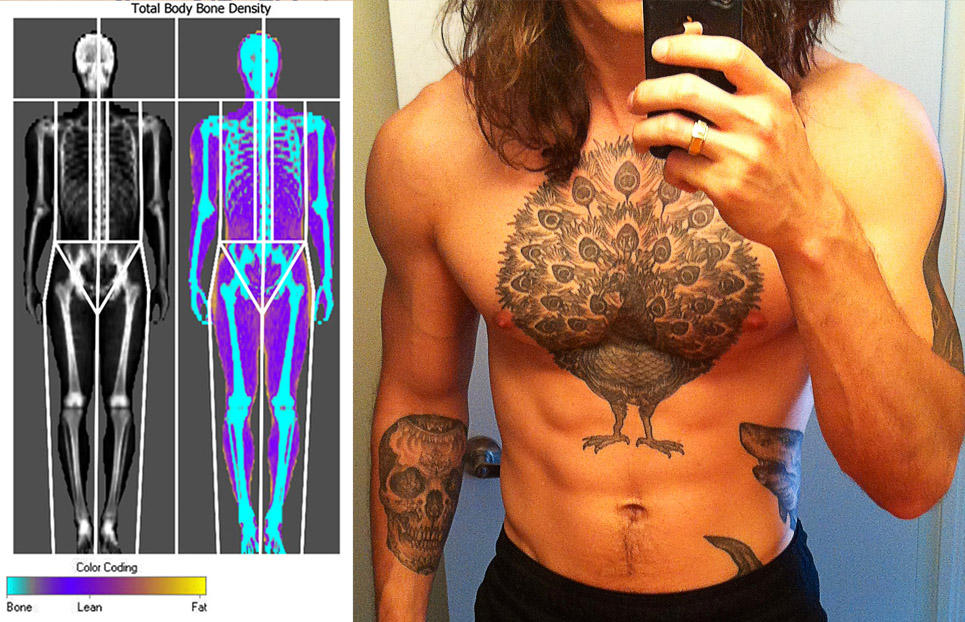

Fast forward to my thirtieth birthday, and my heart specialist had me go to three different clinics to confirm my blood markers. He told me that in his entire career, he’d never seen someone make such a profound improvement to their general health. I’d been lifting three times per week for the past decade, I was going on daily walks, I had improved my diet, I had overhauled my sleep, and I had gained sixty pounds at 11% body fat:

Now, to be clear, the heart specialist didn’t say that lifting weights is what caused my health to improve. He certainly didn’t say that it was the squatting and deadlifting that had improved my health. But adding up all those pieces, my health had taken a profound turn for the better. I had gone from high risk to low risk.

But I don’t want to undersell the importance of those big lower-body lifts, either. By squatting and deadlifting 2–3 times per week for two years, I had gone from doing partial squats with 75 pounds to doing deep squats with 315 pounds. I had gone from doing awkward deadlifts with 95 pounds to doing conventional deadlifts with 425 pounds. Given that our quads and glutes are the two biggest muscles in our bodies and that squats and deadlifts are the two best lifts for improving both bone density and cardiovascular fitness, I have no doubt that they were an important part of my transformation.

The research on lower-body strength is compelling, too. Here’s a study on the brain function of identical twins as they age. The guys with stronger legs had better brain function and more grey matter than their identical twins, showing that lifting heavy can physically change our brains.

Doing a ten-rep set of squats, especially once we get strong at them, is quite similar to doing a hundred-meter sprint in terms of how much it demands of both our aerobic and anaerobic systems. If we rest a couple of minutes and then do another set, and then another, then we’re essentially doing high-intensity interval training (HIIT). We’re combining intense exercise with short periods of rest, and the effect on our general health can be profound.

Now, there are heavy compound upper-body lifts, too, such as the chin-up, the overhead press, and the bench press. But there’s a reason why people dread doing ten-rep sets of squats and deadlifts more than they dread a ten-rep set of bench presses. With the upper-body lifts, we aren’t engaging as much overall muscle mass, and so our aerobic systems aren’t being worked nearly as hard. The cardiovascular adaptations aren’t comparable.

To make things even more interesting, ten weeks of doing heavy squats has been shown to double our expression of a gene (PPAR-delta) that improves our ability to burn fat for energy (study). Not only could this make it easier to burn fat, but it could also potentially make it easier to stay leaner. And this is just one gene. The squat is a huge lift, and rigorous squat training causes us to adapt on many, many levels.

Squatting & Deadlifting for General Strength

The bigger our muscles are, the stronger they are. And the stronger our muscles are, the more force they can exert. This affects our ability to generate explosive force, too, so having bigger legs doesn’t just mean that we can lift more weight, it also means that we can run faster and jump higher. This makes deadlifts great for helping us lift heavier things off the ground, yes, but they’re also great for improving our general athleticism. The same is true with squats.

Moreover, lifting with a large range of motion is great for improving flexibility, and bigger muscles tend to be longer ones. Perhaps more importantly, we develop strength and control through that range of motion, improving our mobility. As a result, squatting and deadlifting are some of the best ways to improve our overall mobility and coordination.

When it comes to injury prevention, heavy squats and deadlifts do the best job of strengthening bones, tendons, muscles, and connective tissues. Stronger glutes and lower back muscles probably reduce the risk of developing lower-back pain.

How Big is Too Big?

It’s pretty common for a guy to secretly skimp on his lower body training, but it’s very rare for a guy to be crazy enough to argue that we should be skimping on our lower body training.

Let me be that crazy person for a moment.

The Problem with “Big Three” Lifting Routines

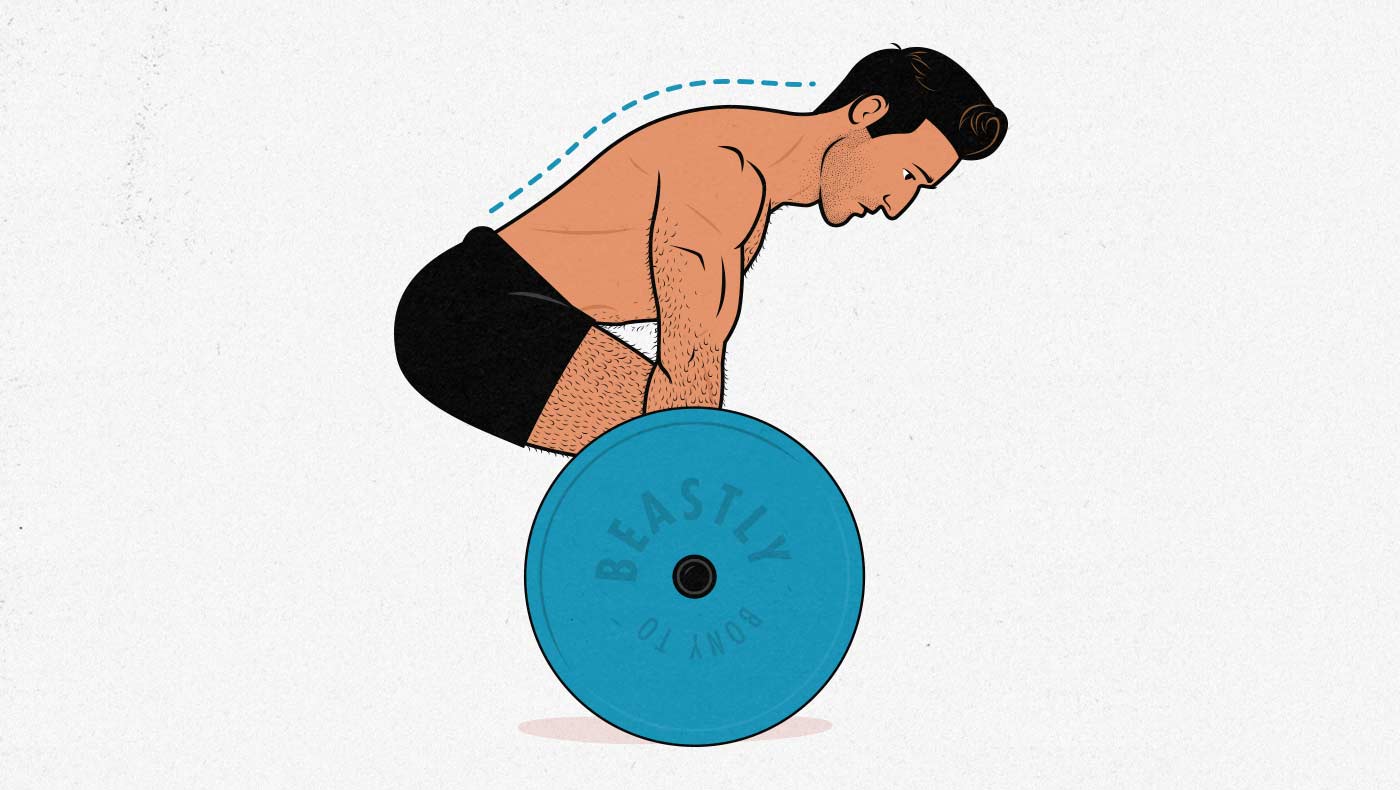

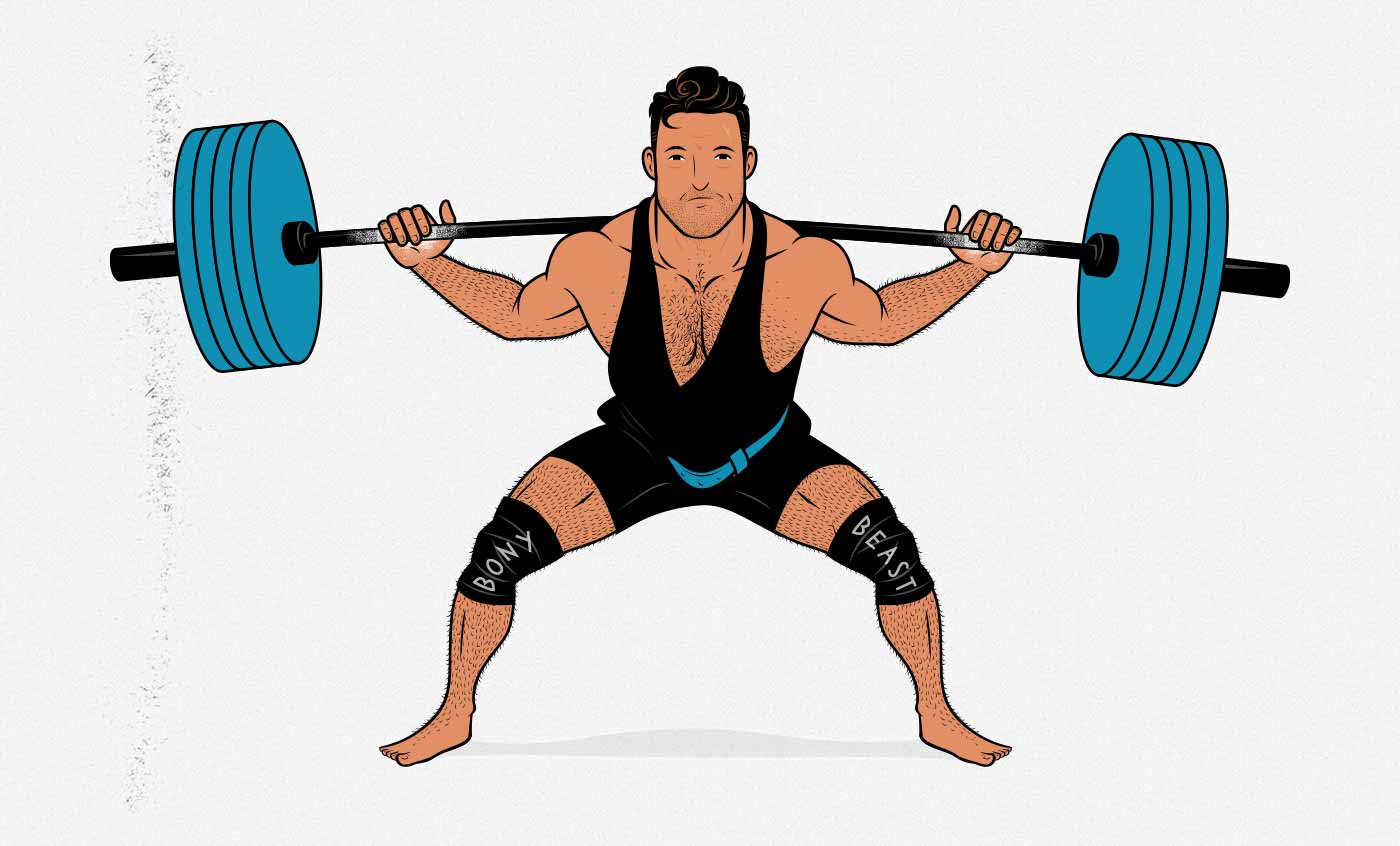

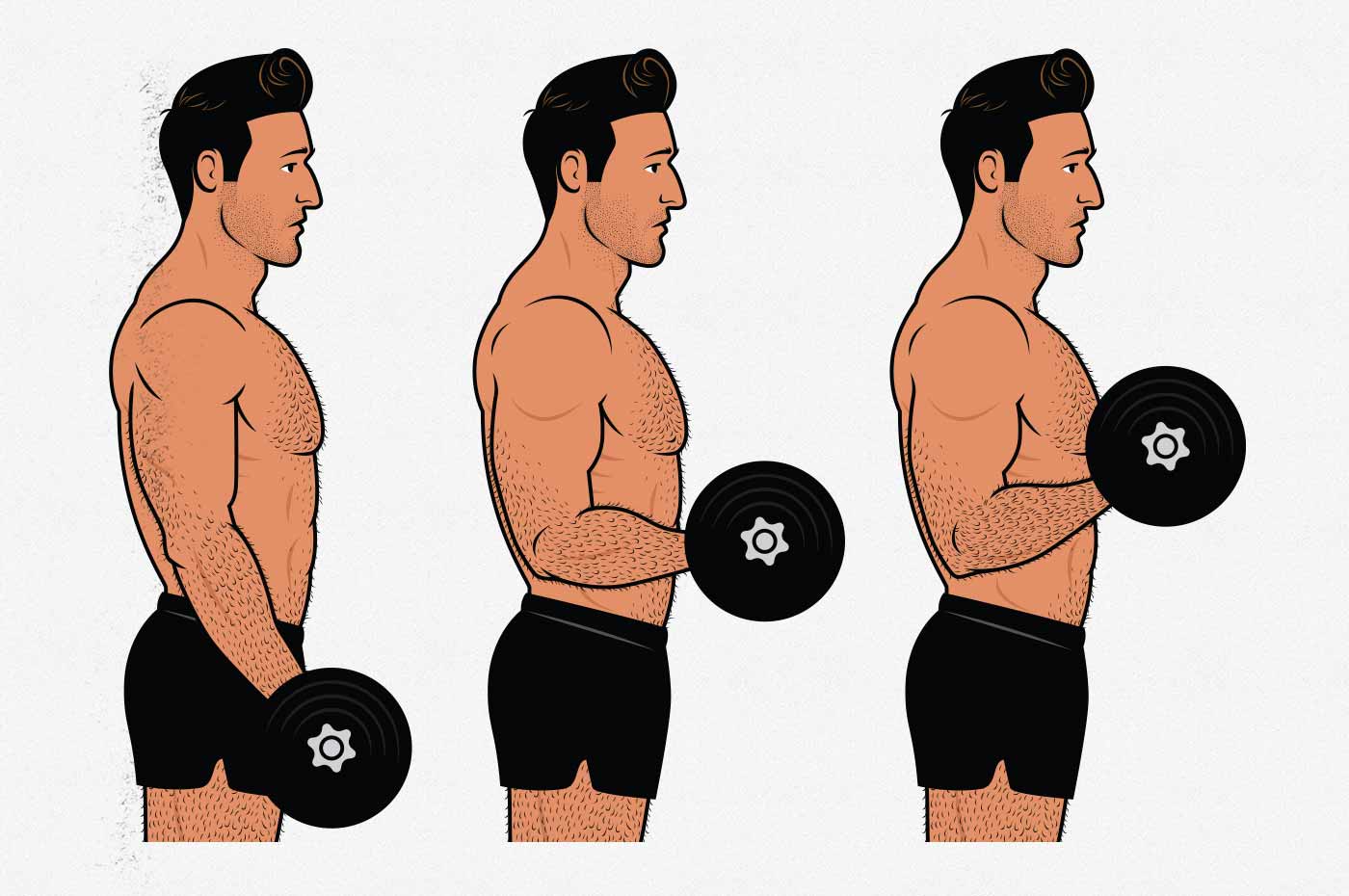

Most serious lifters are serious enough to follow a good workout program. All of the best workout programs include some form of squat (for the quads, glutes, and calves) and deadlift (for the hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors). In fact, most of those programs have a strength training bias, which often means starting the workout with heavy sets of low-bar back squats:

As controversial as this sounds, especially in strength training circles, this creates the opposite problem, where a lot of serious lifters have disproportionately large legs. And I don’t just means that they’re legs look too big, I mean that we have guys who can squat 400 pounds without being able to do ten chin-ups.

I’d argue that unless we’re powerlifters, we should care about more than just our squat, bench, and deadlift. Those are great lifts, but they aren’t the only great lifts. For example, the chin-up and overhead press are just as important for building well-rounded strength, and they have a far bigger impact on our appearance. As a result, we prefer to use a “Big Five” approach to bulking, where we focus equally on the squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead press, and chin-up, shifting our workouts from 33% upper body to 60% upper body.

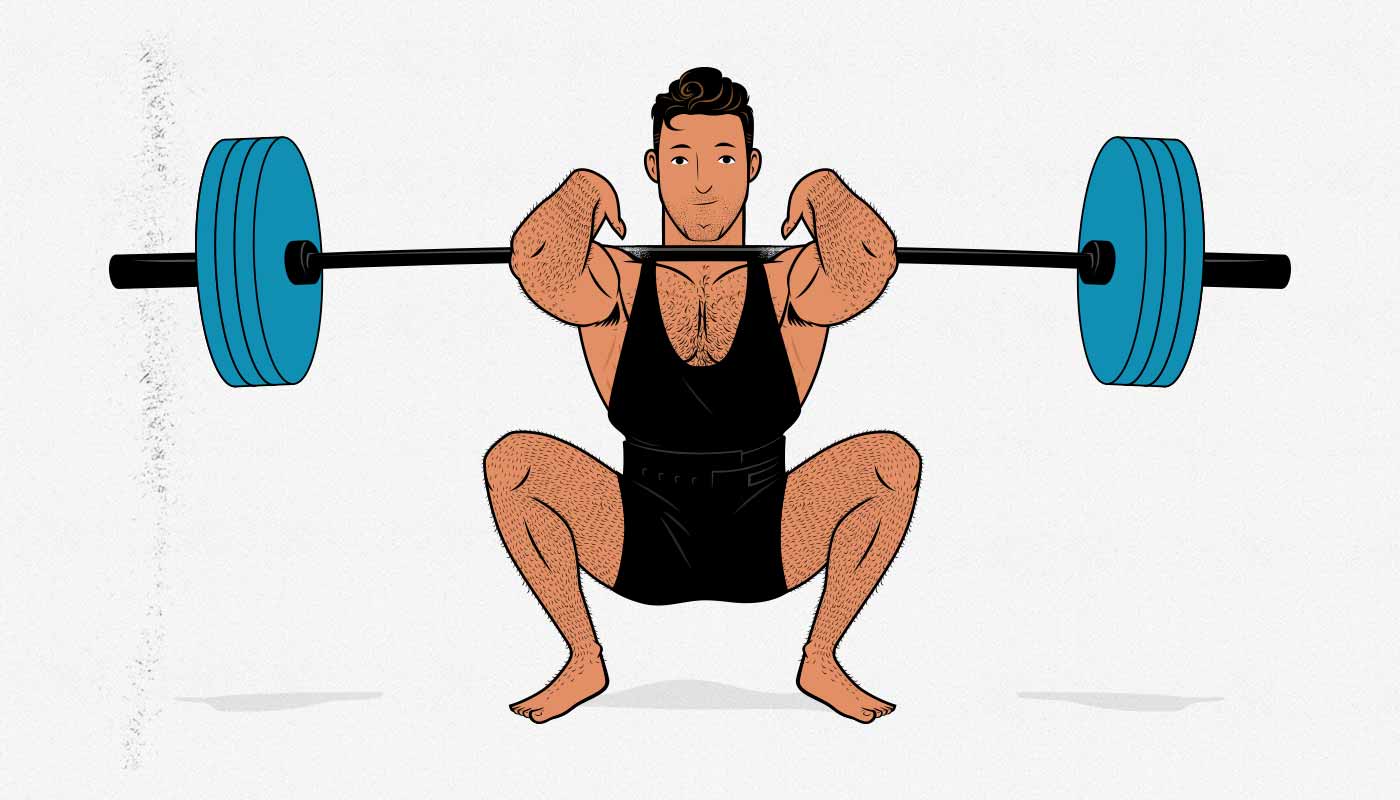

The other thing to consider is that there are several variations of squats and deadlifts, each with their own unique advantages and disadvantages. If we follow in the footsteps of powerlifters, doing the low-bar back squat and sumo deadlift, we’re optimizing our routines for powerlifting performance, not for our health, general strength, or aesthetics. I’d argue that we’d get more benefit by choosing variations that incorporate our upper bodies a bit more, such as the front squat and conventional deadlift:

- The Front Squat: for our quads, glutes, and upper backs.

- The Bench Press: for our chests, shoulders, and triceps.

- The Conventional Deadlift: for our hamstrings, glutes, and lower backs.

- The Overhead Press: for our shoulders, triceps, and cores.

- The Chin-Up: for our upper backs, biceps, and abs.

The other popular trend in Big Three routines is to focus on lower rep ranges for the squat, bench press, and deadlift but then to use moderate rep ranges for upper-body accessory work. For example, the workout might start with five-rep sets of squats but finish with ten-rep sets of barbell rows or biceps curls. That isn’t necessarily a problem for building muscle, but it means that we’re never squatting or deadlifting for more than five reps per set.

If we want the general health benefits of squatting and deadlifting, some of those benefits come from lifting in moderate rep ranges. That’s how we get more overall work done, and it’s how we stress our cardiovascular systems. For example, let’s say that someone can squat 275 for five reps for a total of 1375 pounds lifted per set. That same person could probably squat around 225 pounds for ten reps, which is a total of 2250 pounds lifted. In this case that’s 1.65x the amount of work being done. That’s why high-rep sets of squats and deadlifts leave us so winded. We’re doing more work. And that extra work can tax our cardiovascular systems enough to provoke robust adaptations.

Men with Bigger Upper Bodies are More Attractive

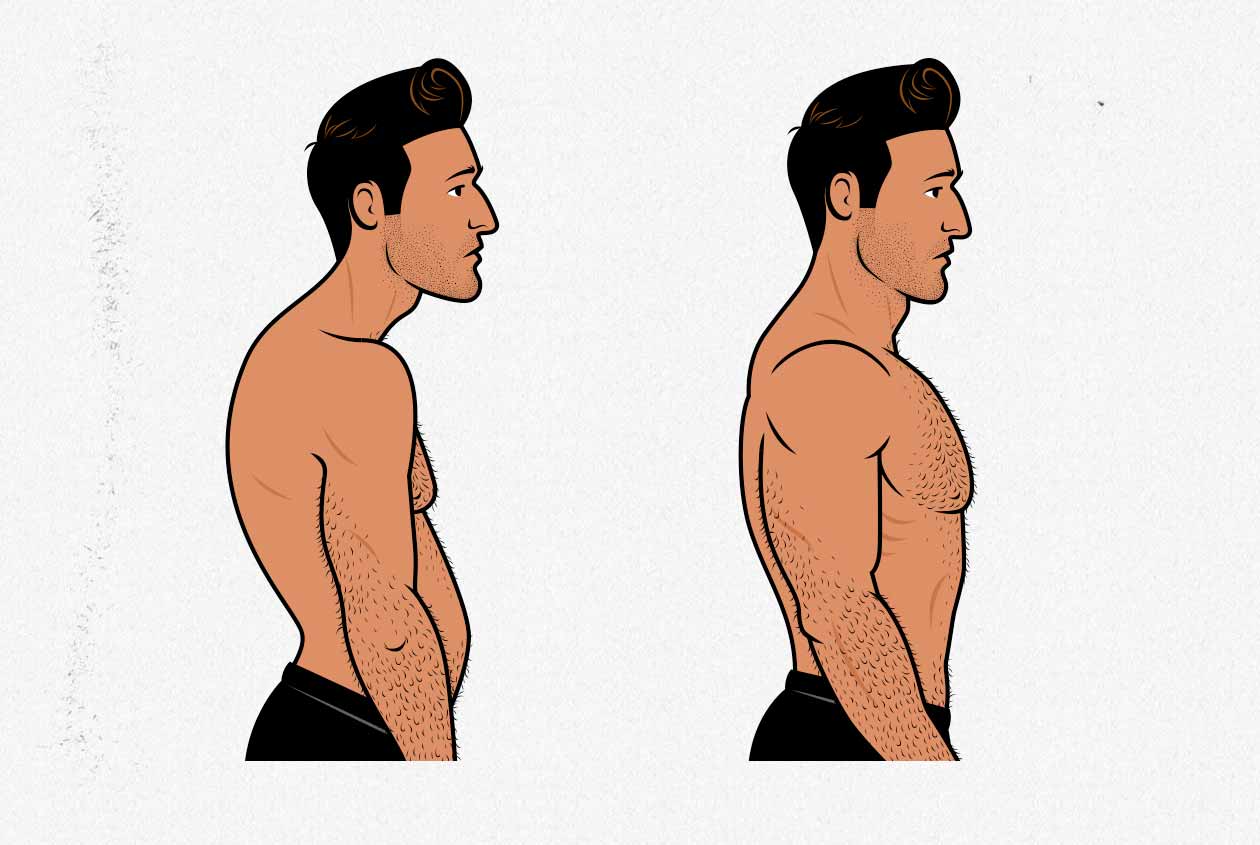

Are squats and deadlifts good for improving our aesthetics? It’s possible to have such small legs that it negatively impacts our appearance, but it’s actually surprisingly rare. Most of the aesthetic benefits we get from squats and deadlifts are from their ability to help us improve our posture and build more muscle in our traps and spinal erectors. Except in extreme cases, building bigger legs doesn’t really seem to impact our aesthetics at all.

Most people are overweight, and overweight people tend to have proportionally stronger legs. After all, they need to carry their bodies around, including up flights of stairs, and that tends to build a fair amount of muscle in the legs, glutes, and lower backs. That’s not always the case, but it’s often the case.

Among lifters, you’d think that with all of these people benching instead of squatting and curling instead of deadlifting, we’d be seeing a bunch of guys with huge chests, big biceps and tiny legs. But that’s actually quite rare. Most guys who are good at lifting weights include some squats and deadlifts in their routines, so most people with muscular physiques are fairly muscular overall. The guys who aren’t good at lifting weights might prioritize upper-body training, yes, but they often gain ten pounds, and then that’s it. They plateau for the rest of their lives. They never build enough muscle to become all that disproportionate, and if they do, they usually fix it.

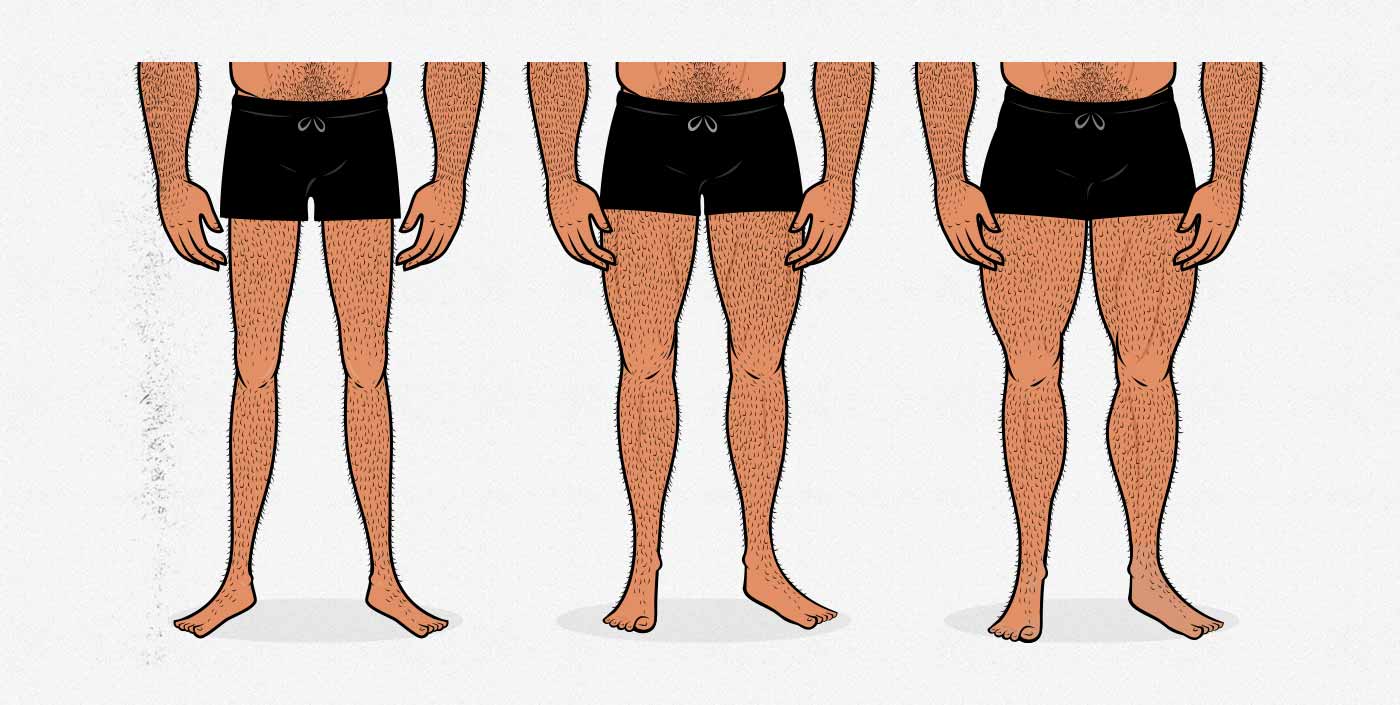

With naturally thinner guys, though, it’s more common to see stilt-like legs, and it’s absolutely possible to bulk up our upper bodies without paying enough attention to our legs, giving us a top-heavy appearance. It’s also common to see guys who squat without deadlifting, developing bigger quads but not hamstrings.

However, most research looking into male attractiveness has been finding that lower-body strength doesn’t seem to have a large impact on our appearance. Having a stronger upper body scales almost perfectly with attractiveness, with stronger upper bodies being consistently rated as more attractive, but that same effect doesn’t seem to be true with our legs (study). As long as our legs aren’t obviously disproportionately small, they don’t seem to have any effect on our appearance. This lines up with the results of our attractiveness survey, too.

Now, why is that? Why is it only the size and strength of our upper bodies that affect our attractiveness? I spoke with the lead researcher in the above study, Aaron Sell, PhD, and he explained that male attractiveness is linked to our formidability, which is linked to how good we are at fighting: punching, wrestling, swinging clubs, and throwing spears. It’s our upper-body muscles that determine how formidable we look. That shouldn’t even come as much of a surprise, given that wrestlers, boxers, and UFC fighters tend to have proportionally bigger upper bodies.

Now, as we mentioned above, that doesn’t mean that squats and deadlifts can’t be used to improve our appearance. If we choose front-loaded squats instead of back squats, we can increase the demands on our spinal erectors, which will give us a stronger and thicker torso, as well as help to improve our posture. That can absolutely improve our aesthetics.

Furthermore, one of the main benefits of the conventional deadlift is that it does such a good job of bulking up our entire posterior chains, including our hamstrings and glutes, yes, but also our spinal erectors, lats, and traps. As a result, the conventional deadlift is one of the very best lifts for improving our aesthetics, it’s just that it does so by helping us bulk up our upper bodies.

Bigger Upper Bodies Look More Masculine

When men hit puberty, they begin to produce more testosterone, their spines grow longer, and their shoulders grow broader. If they gain fat, most of that fat is dumped in their guts, giving them longer, wider, and bigger upper bodies.

When women hit puberty, their hips grow broader, and their legs grow longer. If they gain fat, most of it’s stored in their lower bodies—in the hips and thighs. So, even without considering muscle mass, men tend to have bigger upper bodies than women.

Then, when it comes to gaining muscle, men have more androgen receptors in their upper backs, upper arms, chests, and shoulder muscles, meaning that we tend to build muscle there more easily. As such, a “manly” physique is associated with having big shoulders, chests, and backs.

With women, the opposite is true. They have more androgen receptors in their lower bodies and fewer in their upper bodies. As they gain muscle and strength, they’ll gain more of it in their hips and legs. As a result, a “feminine” physique is often defined by big hips and thighs.

This makes men naturally more upper-body dominant and women more lower-body dominant. As we get stronger, that dimorphism only widens. Still, with enough deliberate effort, we can build massive lower bodies. For example, if we start every workout with squats, that’s where most of our energy will be invested, and we’ll wind up gaining a lot of lower-body size without gaining a proportionate amount of upper-body size.

Starting every workout with squats might sound extreme, but that’s what you’ll see in many popular strength programs, such as Starting Strength and StrongLifts 5×5.

In fact, most workout programs that are oriented around powerlifting or strength training are going to put most of their emphasis on the squat, deadlift, and bench press, which is going to result in most of your gains going to the lower body. After all, that’s where most of your effort is going.

What’s interesting is that the powerlifting lifts are fairly arbitrary. They weren’t chosen because they were the best lifts, they were chosen because they made for great competition lifts. Other lifts, such as the chin-up and the overhead press (and perhaps even the barbell curl), are just as good for developing overall strength, but for various reasons, they weren’t selected as the official competition lifts.

Let’s consider those two lifts for a second:

- Chin-ups develop the upper back, biceps, and abs.

- Overhead presses which develop the shoulders, upper back, upper chest, and triceps.

If we added these two lifts to the big three, we’d have a program that was more effective for developing overall functional strength, given that our body would be proficient at these other important movement patterns. Our legs would still grow big, but with three of the five big lifts being upper-body lifts, our upper bodies would grow proportionally far bigger.

Our Lower Bodies Don’t Need to Be Infinitely Strong

A few years ago, I went to get a DEXA scan for an article we were writing on body fat percentage. Here in Toronto, the main place to get DEXA scans is at The Bone Wellness Centre, so, along with my body-fat analysis, I got a bone-health consultation from the expert there. I had only been lifting for a few years, but my bone density was already (literally) off the chart. Now, it’s not that my bones were actually that dense, it’s just that the chart wasn’t designed for athletes or lifters, it was designed for people in the general population who were trying to improve their bone health. She explained that there wasn’t really any room for improvement—my bone density wasn’t just in the healthy range, it was at the very top of the healthy range.

At the time, I was squatting 275 pounds and deadlifting 375. Now, I’m squatting 325 pounds and deadlifting 425. Is that better for my general health? And is there really a reason to think that reaching my goal of squatting 400 pounds and deadlifting 500 pounds would improve my general health even more? I’m not so sure. There’s no doubt that building a strong deadlift is fantastic for our brains, our general health, and our overall athleticism, but as we get ever stronger, the risk-to-reward ratio increases. In fact, it’s actually quite rare to see elite powerlifters who aren’t nursing some aches, pains, and injuries.

But I wanted to make sure, so I asked Greg Nuckols, MA. Nuckols is a respected researcher and a record-holding powerlifter, and he runs the powerlifting site Stronger by Science. He guessed that after we can squat about 1.5 times our body weight with great technique, we’ve already gotten most of the general health benefits of squatting. He explained that doing heavy high-rep sets was certainly taxing on our cardiovascular systems (which is a healthy form of exercise), but that squatting extremely heavy for low reps was more of a powerlifter thing. And powerlifters aren’t doing it to improve their health, they’re doing it to win at their sport. And they’re willing to hurt themselves to do it.

Upper-Body strength is Often Our Limiting Factor

Back when I was a skinny guy, I was physically incapable of lifting heavy things. Picking up a heavy piece of furniture was a total no-go. My spinal erectors just weren’t strong enough to hold my back in a safe position, my hips weren’t mobile enough for me to bend down with good form, and my grip wasn’t strong enough to hold onto anything heavy. I’m grateful that I didn’t throw out my back like my dad did. He was also skinny, and a bad moving day left him with a lifelong injury that he still deals with today, several decades later.

However, after gaining sixty pounds of muscle and getting 4x stronger at squats and deadlifts, I haven’t run into a single lower-body strength issue. Not once. Now, I’m not saying I’m strong enough to lift absolutely everything. I’m not. But when I find myself unable to lift something, it’s never my lower body that’s the weakest link. My fingers give out, my traps ache, and my biceps burn. It’s the same thing when I’m carrying around my wife or kid. Same with moving furniture or carrying groceries home. My legs aren’t the problem. In fact, I can’t think of a single time since deadlifting 225 pounds that my lower-body strength has been a limiting factor. The main benefit from going from a 225-pound to a 415-pound deadlift isn’t that it made my lower body stronger, it’s that it made my spinal erectors, upper back, and forearms stronger.

Squats and deadlifts are still important, but so are the bench press, overhead press, chin-up, row, and biceps curl. Spending more time strengthening those upper-body muscles may strengthen our weak links better. We can also choose lower-body lifts that help strengthen our upper bodies, such as conventional deadlifts, front squats, and Zercher squats.

Big Legs Don’t Fit into Pants

This sounds like a stupid point to make, and to a certain extent, it is. It seems backward to shape our bodies to our clothes instead of shaping our clothes to fit our bodies. But realistically, most of us will be buying clothes from regular stores, and I wish somebody had warned me that building bigger legs would prevent me from wearing Levi’s jeans.

Now, this problem doesn’t affect everyone equally. Overweight people buy pants with larger waist sizes, and those larger waist sizes allow for larger butts and thighs. However, for those of us who are lean, having legs that are too big can become a real problem when buying pants. As Gregory O’Gallagher (from Kinobody) pointed out, if you keep going hard with the leg lifts, at a certain point, you’ll need to start buying a too-large waist size or switch over to pants designed for overweight people.

Like us, O’Gallagher wasn’t saying that we should have small, weak, or useless legs—he can deadlift over 405 pounds and squat over 315 pounds—just that there’s a point of diminishing returns where getting even stronger can start to make it harder to look good in regular clothes.

For the serious lifter, that might not matter. Greg Nuckols squats over 700 pounds and lives in athletic shorts. No problem. But not everyone is a serious lifter. Some people want to be able to fit into pants.

Squats Won’t Make Our Upper Bodies Bigger

There’s an old idea among bodybuilders that doing heavy squats mixed in with our upper-body training can help us bulk up our upper bodies. The idea is that it’s the big lower body lifts, such as squats and deadlifts, that stimulate the strongest anabolic hormone response—more testosterone, growth hormone, and IGF-1. That’s true, yes, and a few notable studies are often thrown around, but if we take all of the research into consideration, the effect largely disappears. To quote Brad Schoenfeld, PhD, who published the paper reviewing all of the studies done thus far:

What seems relatively clear from the literature is that if a relationship does, in fact, exist between acute systemic factors and muscle growth, the overall magnitude of the effect would be fairly modest.

Brad Schoenfeld, PhD

Furthermore, we have to factor in the opportunity cost of doing more lower-body training. If we do three sets of squats instead of five, that means we can do a few more sets of upper-body training. And there’s no doubt that an extra set of bench presses stimulates more chest growth than an extra set of squats.

What’s the Ideal Leg Size?

To find your ideal leg size, take your waist measurement and multiply it by 0.75. According to Casey Butt, PhD, that number is your ideal thigh circumference measured at the midway point between your knee and hip joint with your muscles relaxed. Note that for this to work properly, your waist needs to be quite lean. If you’re over 15% body fat, you might want to use your ideal waist size instead of your current waist size.

- Ideal thigh size: waist × 0.75

To get this specific calculation, Dr. Butt used the proportions found in statues of ancient Greek warriors and combined that with modern attractiveness research to come up with the most attractive male proportions. So the idea is that these proportions reflect the physique of a man who’s both strong and healthy, as an ancient warrior, Greek wrestler, or Olympic athlete would be.

What’s interesting is that the ideal leg size isn’t very big. For me, with a waist size of 31–32 inches, that gives me an ideal thigh size of around 24 inches. Nobody would consider those small legs, but they aren’t very big, either.

What Leg Proportions are the Most Attractive?

If you want to know all about building an attractive body, we’ve got an in-depth article on aesthetics here. To make a long story short, though, women are, on average, attracted to guys with big upper-body muscles (study). In fact, the perceived strength of our upper bodies accounts for around 70% of the attractiveness of our physiques overall, dwarfing factors like symmetry and posture. After the strength of our upper bodies, the other two important factors are body-fat percentage and height. They barely noticed how big our lower bodies were, provided that they looked reasonably athletic.

We should note, however, that the highest-quality studies involved looking at real men (mostly in college), and most men with muscular upper bodies also have muscular lower bodies. So even though women weren’t noticing the men’s legs, presumably, these weren’t guys who were only bench pressing and doing barbell curls. It’s certainly possible that disproportionate or unathletic physiques would have been rated as less attractive.

The people who care about how big our lower bodies tend to be powerlifters, which makes sense, given that the squat is 1/3 of their sport, and bodybuilders, who care about how big every muscle is. But even then, most bodybuilders have traditionally favoured a V-taper physique with a proportionately bigger upper body. It’s only recently that professional bodybuilders have begun to favour larger legs.

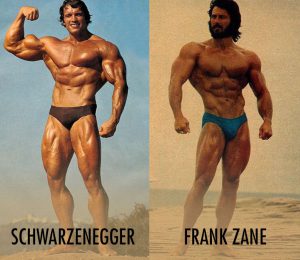

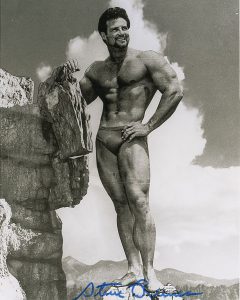

For example, back in the golden era of bodybuilding, which most people consider the golden age of aesthetics, you’d have guys like Frank Zane and Arnold Schwarzenegger winning the Mr. Olympia title, and they had rather large upper bodies compared to their lower bodies:

This was reflected in their training routines, too. Squats were important but not nearly as important as upper-body training. Most of their workouts would start with a couple of upper-body lifts before moving on to some lower-body training. It’s not that they had naturally smaller legs, it’s that leg training was seen as less important than upper-body training.

Nowadays, however, bodybuilding is all about the X-physique, with squats, leg presses, and leg extensions becoming far more dominant in bodybuilding routines. For example, here’s the most recent Mr Olympia winner, Phil Heath:

It takes a lot of effort to build legs that big, and I appreciate that—it’s impressive—but it’s an extremely niche sport. Most women don’t find those physiques attractive, and most men don’t want to look that way. That goes for Arnold Schwarzenegger, too, mind you. Most women consider him too bulky. Even in his heyday, he was getting roles as the action hero, barbarian, and killing machine, not the heartthrob.

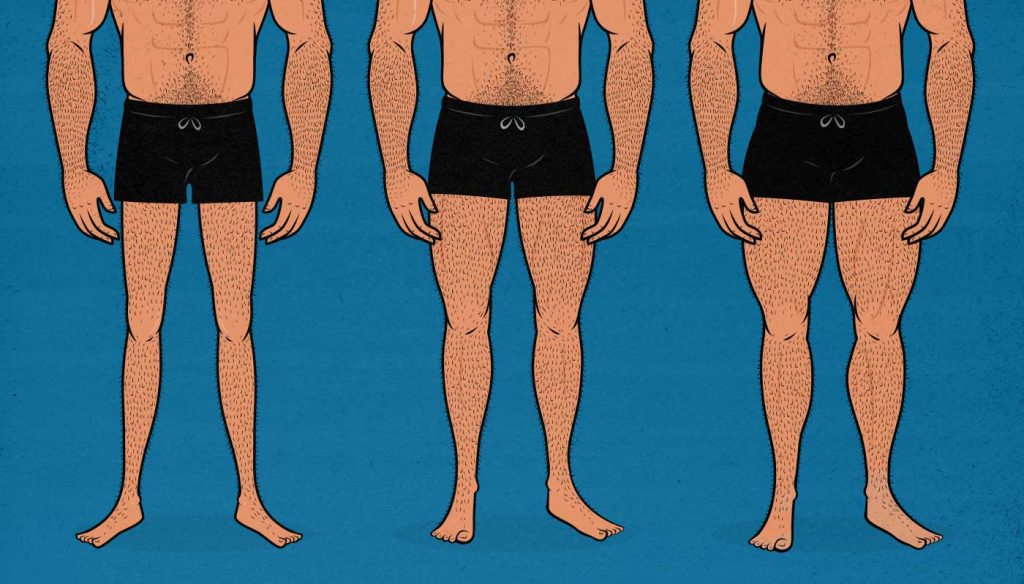

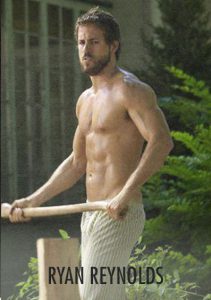

If we look to the physiques that women find more attractive (and the kind of physiques that most men want to build), then we start to see men who look less like bodybuilders, and more like Greek wrestlers:

Now, obviously, these physiques are still built by lifting weights. The methods aren’t so different from bodybuilding. Biceps are still built by chin-ups and biceps curls. Shoulders are still built by overhead presses and lateral raises. It’s just that we’re looking at guys with worse muscle-building genetics who spend less time training and who are (probably) not taking performance-enhancing drugs.

However, if you take a look at Ryan Reynolds, there, you’ll notice that, first of all, the person choosing this heartthrob photo didn’t choose a photo where his legs were all that prominently displayed. But even if you look at his thighs, you’ll notice that this is clearly a v-tapered physique. His chest, arms, shoulders, and upper back are much more developed than his legs and butt.

The Most Aesthetic Male Proportions Overall

According to Dr Casey Butt’s guidelines, your hips should be about 25% larger than your waist, your thighs should be about 25% smaller than your waist, your shoulders should be around 62% larger than your waist, and your biceps should be around 50% the size of your waist.

- Ideal waist size: you at 8–15% body fat

- Ideal hip size: waist × 1.25

- Ideal thigh size: waist × 0.75

- Ideal shoulder size: waist × 1.618

- Ideal bicep size: waist × 0.50

For example, here are the ideal proportions for a man who has a 30-inch waist at 12% body fat:

- Waist: 30 inches

- Hips: 37.5 inches

- Thighs: 22.5 inches

- Shoulders: 48.5 inches

- Biceps: 15 inches.

Even for naturally skinny guys, these measurements tend to be realistically achievable, and often within just a couple of years of starting to lift weights.

How Much Leg Work Should We Do?

It’s time to get a little bit technical. Bear with me. The more sets and reps we do with a particular muscle, the more that muscle will grow (meta-analysis). A higher training volume means more muscle growth, at least up to a point. It seems like around 4–8 sets per muscle group per workout is enough to maximally stimulate muscle growth, and going higher than that doesn’t necessarily yield any extra growth.

The next thing to consider is our training frequency. Our muscles grow best if we stimulate them at least 2–3 times per week. So, to build muscle as fast as possible, we want to do 3–8 sets per muscle per workout and train those muscles 2–3 times per week, giving us a total of 10–20 sets per week per muscle. (It’s possible to benefit from training our muscles as many as five times per week, but that doesn’t seem to offer any extra advantage.)

However, there are a lot of muscles in our bodies, ranging from the big muscles like our quads, glutes, shoulders, chests, and lats, all the way to our smaller muscles, like those in our necks and forearms. And so training all of our muscles with a high enough volume can take quite a lot of time and energy. If we’re only lifting weights a few times per week, we might not have enough time to maximize muscle growth in all of our muscles at once. Furthermore, our ability to recover is finite. If our lifting volume is too high in too many different areas, we can start to accumulate fatigue instead of muscle growth.

Plus, some lifts are harder to recover from than others. A squat is quite taxing on our central nervous system, a bicep curl is not. If our workouts have one fewer set of squats, that might leave room for three more sets of curls. If we look at the deadlift, that ratio gets even more extreme, where a few sets of deadlifts can be more fatiguing than entire upper-body workouts. Now, that isn’t to say that squats and deadlifts are bad—they’re two of the best lifts for building muscle—just that they come with an opportunity cost to consider. Since we can only lift and only recover from so much, the price of bigger legs is a smaller upper body, and vice versa.

Finally, the lifts we start our workouts with are going to get the majority of our energy. If a workout starts with squats, we can expect most of the growth stimulus to go to our legs, even if we include plenty of upper-body work afterward. That’s fine, but if every workout starts with squats, we’re selling our upper bodies short. It might make more sense to start some workouts with squats, others with deadlifts, and also to have some workouts where we start off with upper-body exercises.

This means that when designing a workout program, we aren’t just trying to cram a bunch of compound lifts together. We’re trying to pick the lifts that offer us the best returns on our investment and arrange them in a way that best matches our goals.

For example, someone who wants to prioritize leg growth might start their workouts with a few sets of low-bar back squats, investing a ton of energy into bulking up their quads and glutes. But someone who wants to prioritize building broader shoulders might start their workouts with some overhead presses and chin-ups and then do some lighter front squats afterwards. The squatting volume is the same in both cases, but we’d expect the first guy to build bigger legs and the second guy to build a bigger upper body.

I know this might seem like splitting hairs, but if you gain thirty pounds while following one program, you might wind up with a totally different physique than if you gained thirty pounds following another program. If you care about the size, strength, and aesthetics of your physique, that might be something you want to take into consideration when arranging your workouts. And different programs make these judgment calls differently.

The more time and energy we invest in specific muscle groups, the bigger and stronger they’ll grow. If there’s a lift you’re trying to improve at, best to put it first in your workout. If there’s a muscle group you’re eager to grow, better to put it front and centre and do more total sets for it.

Which Style of Training is Best for Our Proportions?

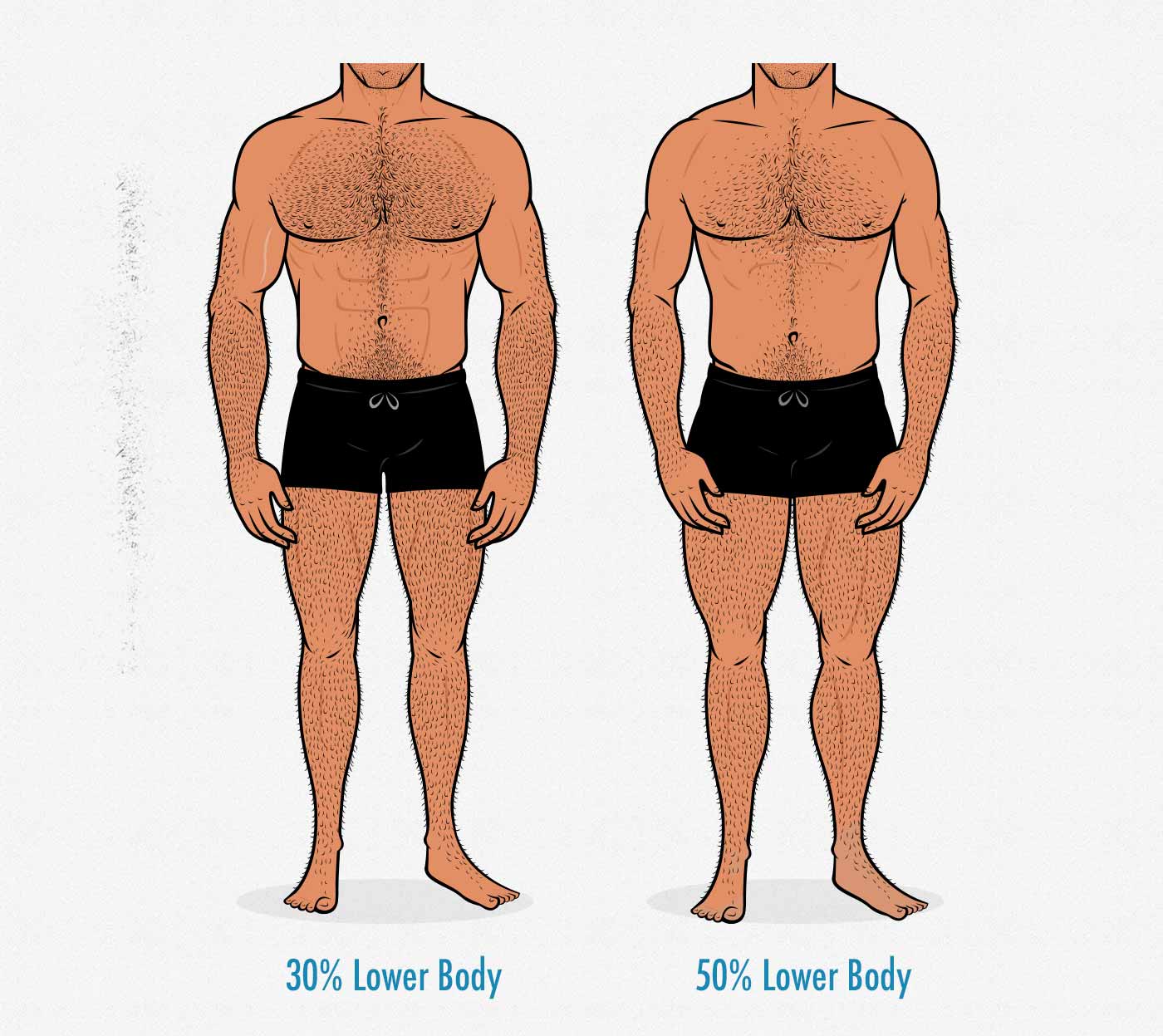

Different workout programs emphasize different lifts, different muscle groups, and different proportions. Some strength training programs train legs three days per week and start every single workout with squats. some bodybuilding programs train legs just once per week, with 2–3 separate workouts devoted entirely to their upper bodies. I would argue that both of those approaches are flawed, but let’s go into a few different popular approaches.

Upper-Lower Split Proportions

An upper-lower split program alternates between upper-body and lower-body days—50% volume for each. This is a great way of training for people who need to prioritize their lower-body strength or who want to build truly massive legs.

For example, it’s common for athletes to train this way, and I’ve seen world-class athletics coaches, such as Eric Cressey, design workout programs like this. If you’re a rugby player, say, then you might want to devote a ton of time to building bigger and faster legs, but you still need your upper body to be big and strong.

Monday: Lower body.

Tuesday: Upper body.

Wednesday: Rest.

Thursday: Lower body.

Friday: Upper body.

Saturday: Rest.

Sunday: Rest.

5×5 Proportions

Depending on the 5×5 program, it might have something like 40% lower-body lifts, 60% upper body lifts. I got that breakdown from Stronglifts 5×5, which is a squat-based program. Starting Strength is similar, just with less volume.

This style of training originated in powerlifting circles. The idea is to gain a lot of strength in the big three powerlifting lifts. Two of the three powerlifting lifts are lower-body lifts, so it makes sense to emphasize the lower body.

- Monday: Full body, squat emphasis.

- Tuesday: Rest.

- Wednesday: Full body, squat emphasis.

- Thursday: Rest.

- Friday: Full body, squat emphasis.

- Saturday: Rest.

- Sunday: Rest.

Push-Pull-Legs Proportions

This kind of program has a push, pull, and leg day, with each of those days having a similar training volume. That’s 67% upper body and 33% lower body. These programs tend to be higher in volume (more lifts per muscle group per week) and thus do better at building overall muscle mass than strength-focused programs. Even these programs tend slightly more towards the X-physique, but depending on your style (and genetics), these can give pretty aesthetic results.

This isn’t my favourite way to design a routine for several good reasons, as outlined in this article, but these programs are not at all bad.

- Monday: Push, size emphasis.

- Tuesday: Rest.

- Wednesday: Pull, size emphasis.

- Thursday: Rest.

- Friday: Legs, size emphasis.

- Saturday: Rest.

- Sunday: Rest.

Big Five Proportions

We use an approach that we’ve dubbed the “Big 5” approach to bulking. It’s built around the squat, deadlift, bench press, chin-up, and overhead press. At first glance, that would make our Bony to Beastly Bulking Program about 60% upper body and 40% lower body.

However, we favour the front squat (or goblet squat), which puts more emphasis on the upper back. Similarly, when we deadlift, we put more emphasis on the spinal erectors.

Finally, we also tend to choose accessory lifts like biceps curls, chest flyes, and lateral raises, which help to develop the muscle groups that most of us care more about. We still squat and deadlift heavy to get all the health and performance benefits—strength, bone density, tougher connective tissues, better cardiovascular health, and so on—but we skip the calf raises and do some extra biceps curls instead.

So what we wind up with is a minimalist routine for our lower bodies, with a more comprehensive approach for our upper bodies. It looks something like this:

- Monday: Full-body strength + upper body size.

- Tuesday: Rest.

- Wednesday: Full-body strength + upper body size.

- Thursday: Rest.

- Friday: Full-body strength + upper body size.

- Saturday: Rest.

- Sunday: Rest.

This isn’t radical, just more classic. In the 1950s, lifters like Steve Reeves would do full-body workouts three times per week that were around 75% upper body. His proportions became so famous that guys still aspire to look like him today.

It’s worth noting that not all aspects of his workout were ideal. Bodybuilding was a new thing back then, and over the past 60 years, we’ve learned a lot more about how to build an optimal hypertrophy program.

He hit the nail on the head by doing three full-body workouts per week, though. Modern research shows it to be the most effective way to bulk up—at least for beginner and intermediate trainees. I think his upper-to-lower-body ratio was spot on as well, although that’s more subjective.

Key Takeaways

Building strong legs is amazing for our health, fitness, brain, and even our appearance. Squats and deadlifts are also the two best lifts for gaining overall muscle mass, improving our overall body composition, increasing our bone density, building stronger connective tissues, and improving our cardiovascular health. Of all the lifts, there’s a good argument to be made that moderate-rep sets of heavy squats and deadlifts do the most to improve our general health.

In fact, having strong, functional legs is important enough that I think we should train our legs 2–3 times per week, doing 4–8 sets of squat and deadlift variations each workout (as part of a full-body workout). That higher frequency gives us the best muscle and strength gains, it’s great for our health, and it still leaves plenty of time and energy to focus on our other lifts (and ideally cardio).

However, leg lifts don’t always need to be front and centre in our training. Not every workout needs to start with heavy sets of squats or deadlifts. There’s nothing wrong with starting our workouts with chin-ups or overhead presses, followed by lighter squat and deadlift variations, such as goblet squats and Romanian deadlifts.

Furthermore, you might prefer choosing lower-body lifts that also improve the strength and appearance of your upper body. For example, the front squat (or goblet squat) is just as good at bulking up our quads and glutes as the back squat, but it also builds muscle in our upper backs and helps to improve our posture. The conventional deadlift is another good example, where it’s great for our hamstrings and glutes as well as for our spinal erectors, traps, lats, and forearms.

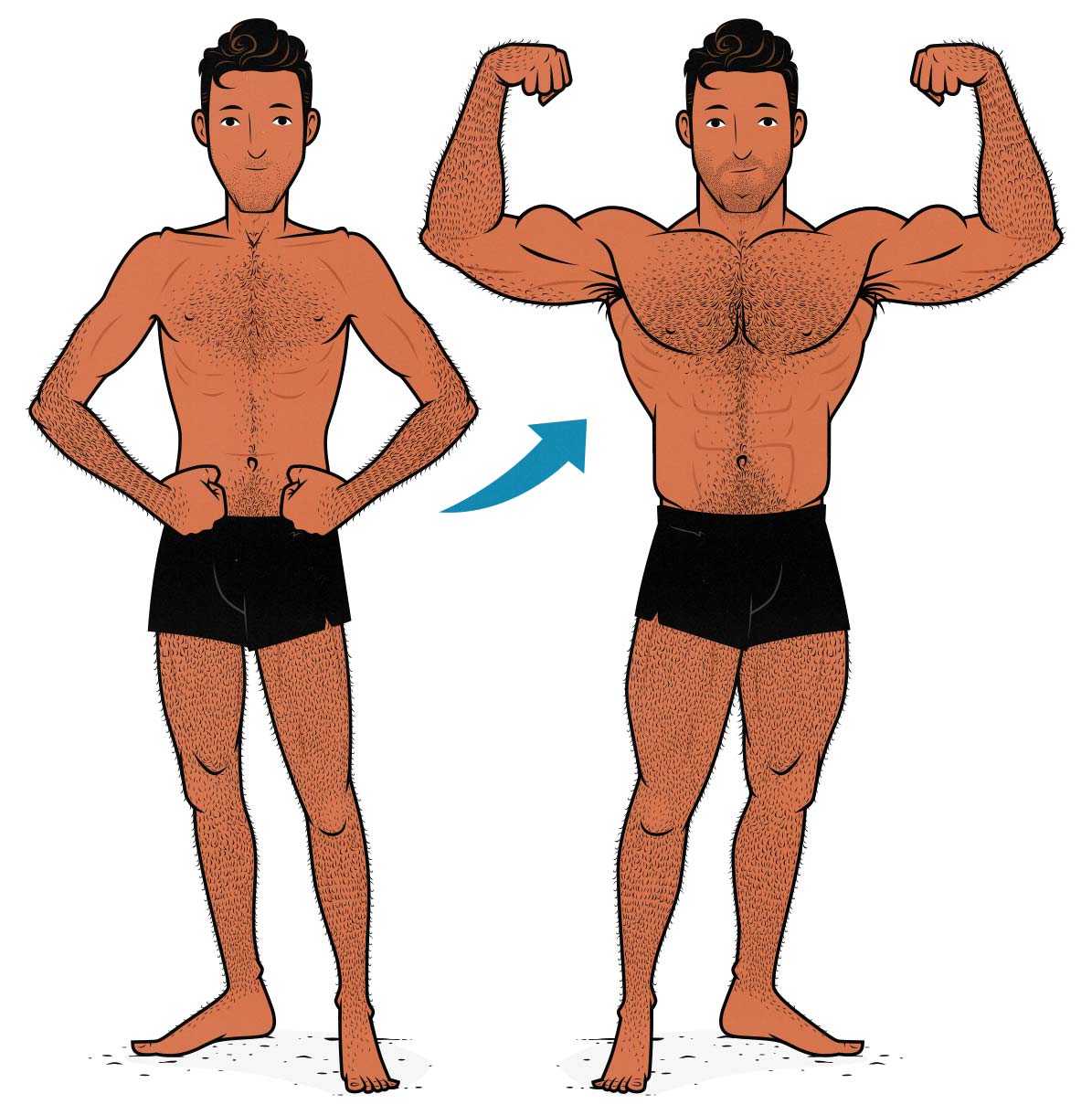

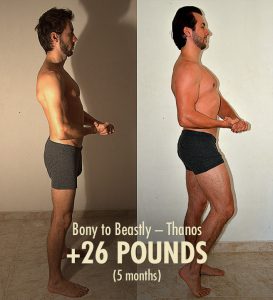

I would argue that this approach actually gives us better general strength, general health, and aesthetics as we bulk up. For example, check out Thanos’ five-month progress photos:

Would he have looked or performed better if he did twice as much leg work and half as much upper-body work? I’m not so sure. In fact, after just a few months of bulking up, I bet he’s already closing in on the most attractive leg size for his frame.

To wrap this up, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with a higher leg volume. But there’s also no sort of moral imperative there either. You can do less if you want to. Or more. Just consider your goals when making that decision.

If you want more muscle-building information, we have a free bulking newsletter for skinny guys. If you want a full bulking program, including a 5-month workout routine, diet guide, recipe book, and online coaching, check out our Bony to Beastly Bulking Program. Or, if you want an intermediate bulking routine, check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program.